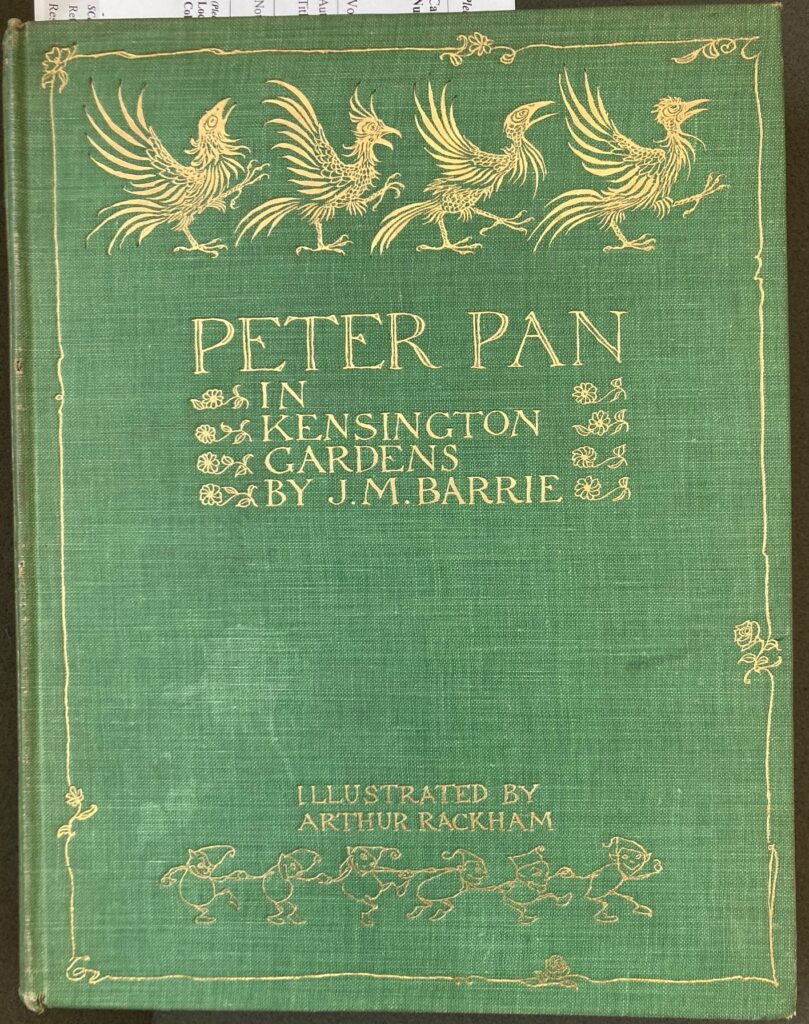

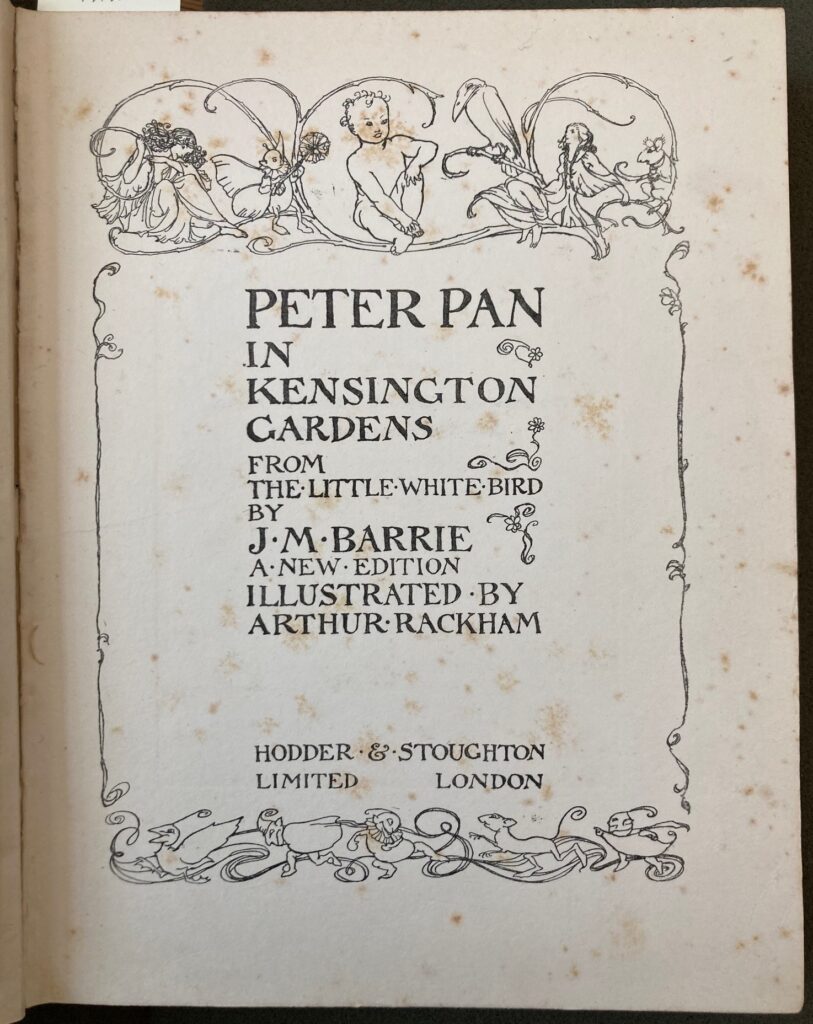

She’s a whimsical thing dressed in buckram-book-cloth boards, a green color somewhere between chlorophyll and parakeet. Small white pores between the subtle cross-hatching lines brightens her texture. She’s adorned with stamped engravings in gold leaf, spelling out the title/author/illustrator and depicting playful illustrations.

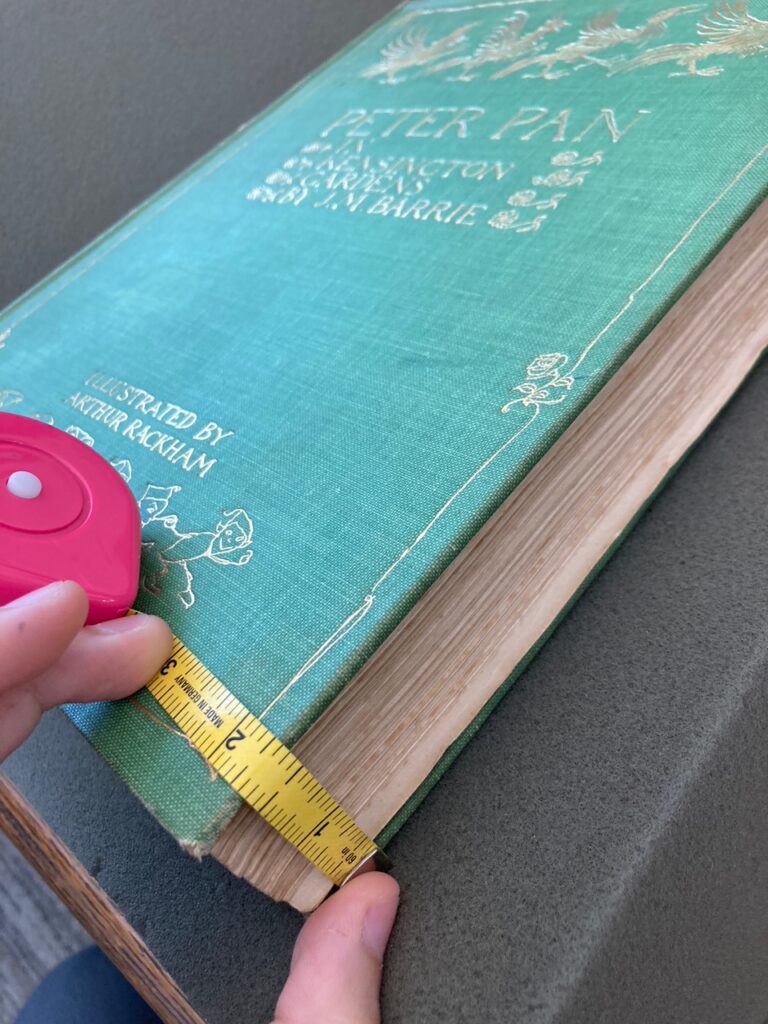

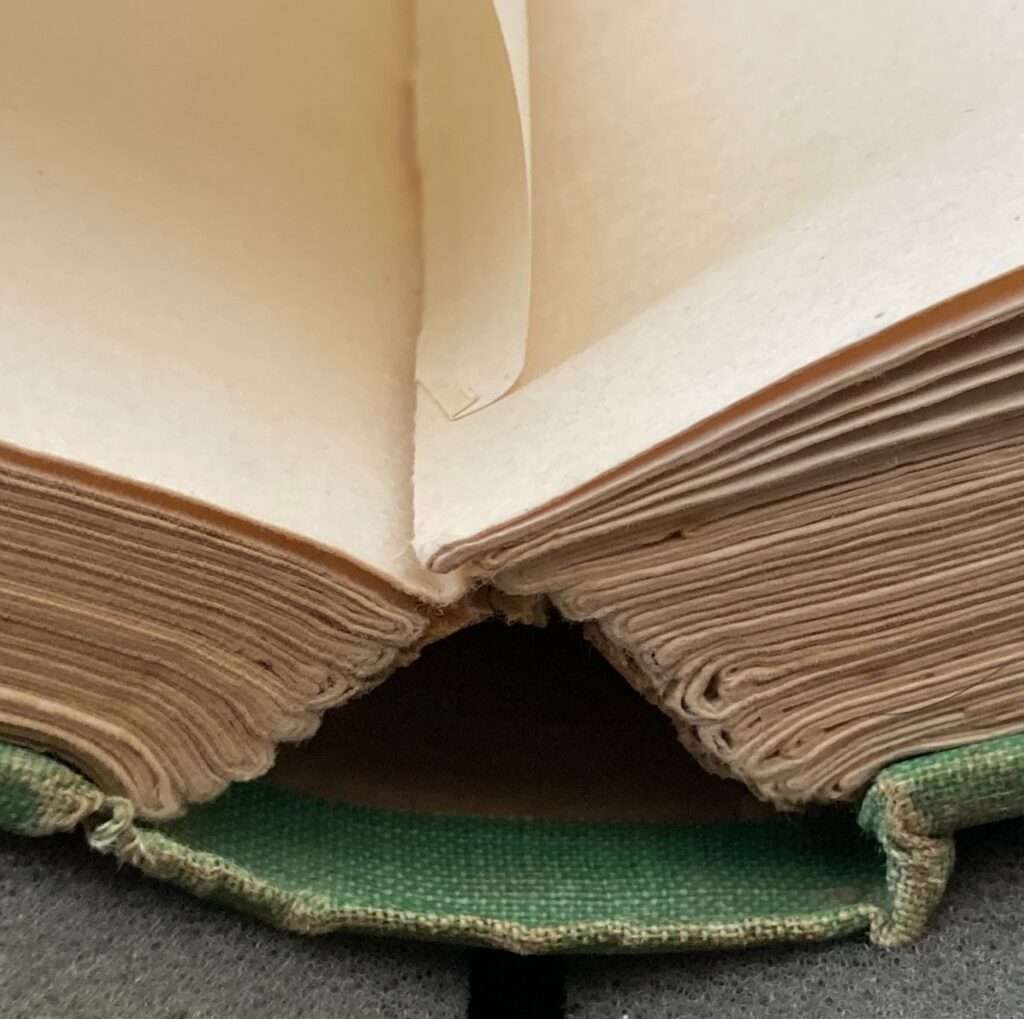

The book is about 11 by 8 inches. She is a great size for sharing – not a book that you curl up with, but instead something you can present and perform, albeit heavy to hold upright. Sturdy, she is 126 pages, two inches thick when closed. When opened, her signatures are distinct, and I can see about 17 bundles from the bottom. Judging by her measurements, she is probably an imperial octavo.

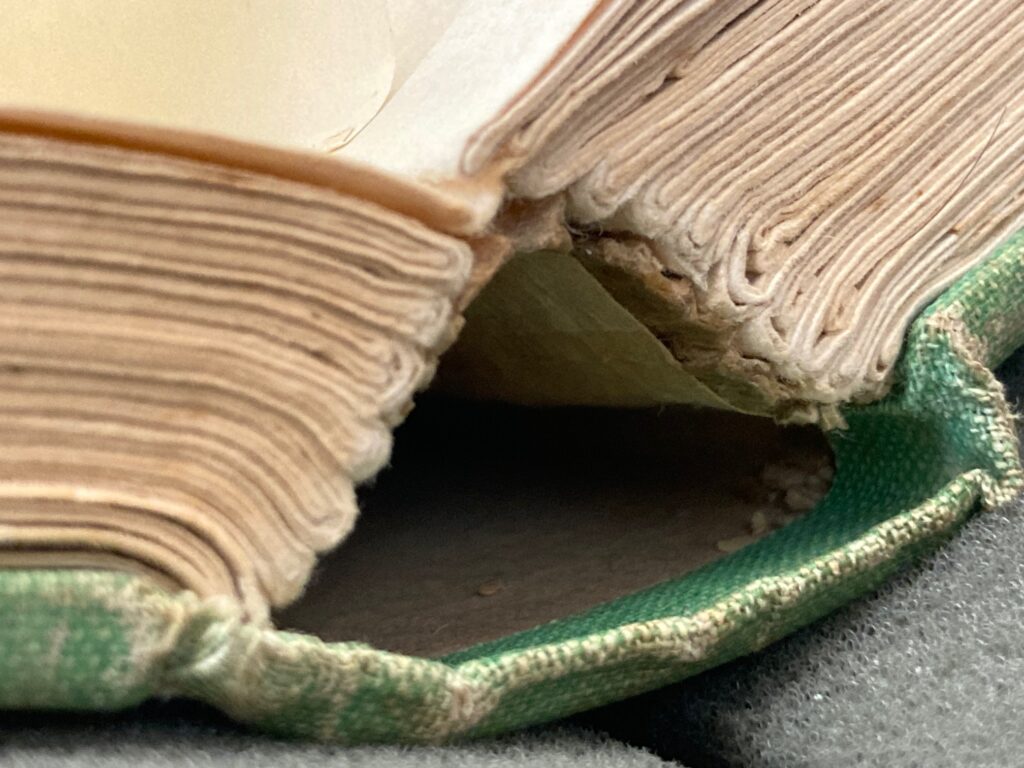

Made via case binding, the endpapers are pasted to the cover boards, but the book spine is not. When the book is splayed open, a tunnel opens up between the hardcover case and the spine of the text block. It reveals the signatures are glued to a worn gauze strip that is attached to the endpapers.

When I open the book up to its more delicate areas, where new signatures begin, I can see a hint of the stitching in the inner crevices of the book. The thread pattern looks like a line between two stitch holes, then a gap, then it repeats:

__ __ __ __ __ __

A dash stitch!

Each page is thick, heavier than the 60-gram paper we sampled in the Book Lab. The corners of the pages are rounded, and the edge of the pages are cut smoothly. The pages are a uniform texture without any ribbed bumps nor oiliness, so it appears woven. When I shine my phone’s flashlight through a page, the glow on the other side appears mushy, scattered. There doesn’t seem to be a grain. Verdict: wood pulp paper. Additionally, ALL of the pages (AND the case) are covered in rusty, orange liverspots called foxing stains. It gives the book an elderly character, like it is grandma telling you about Peter Pan.

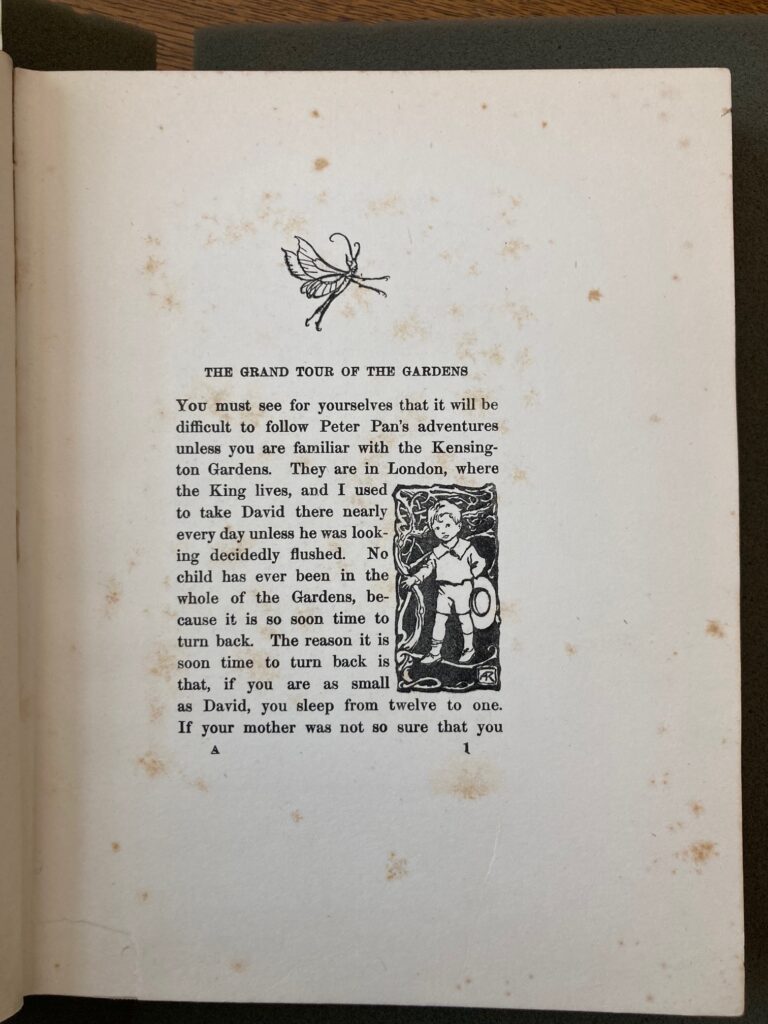

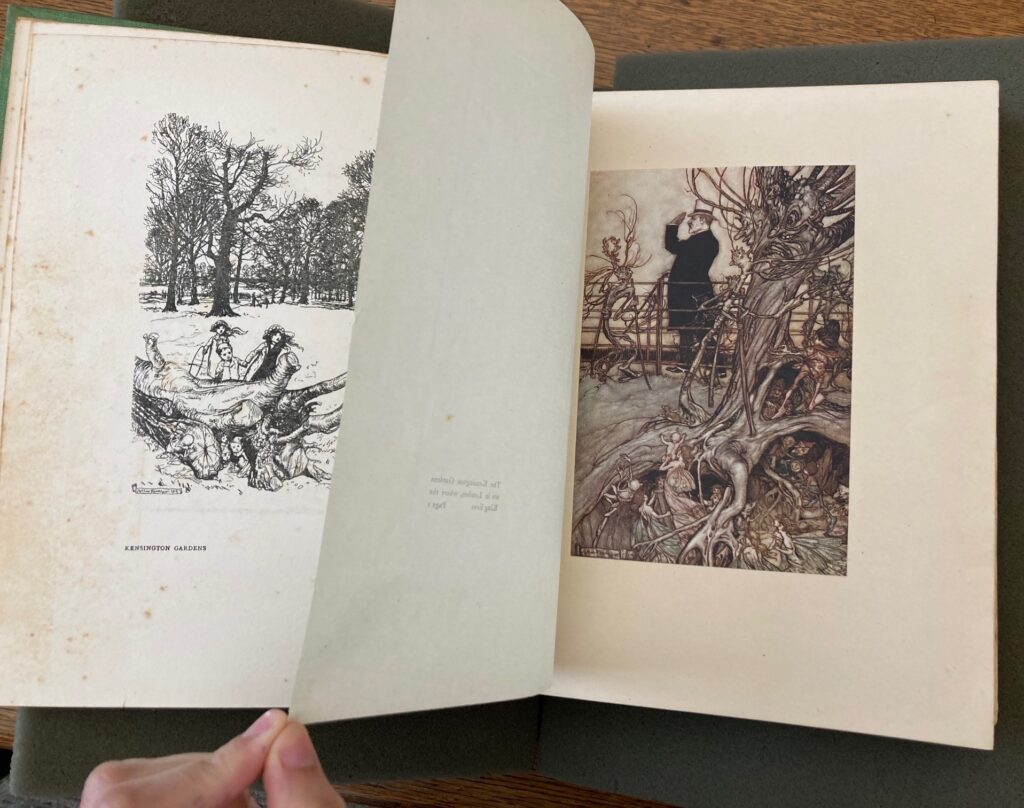

While the pages themselves are large, there is an abundance of blank space. Both the text and the illustrations are centered in a tight rectangle at the topmost half of each page. The illustration styles also vary. On one side of the spectrum, there are black-ink woodblock illustrations that are embedded directly into the pages of the codex. These woodblock illustrations sometimes have a built-in frame, and utilize the darkness of the ink to create high-contrast outlines.

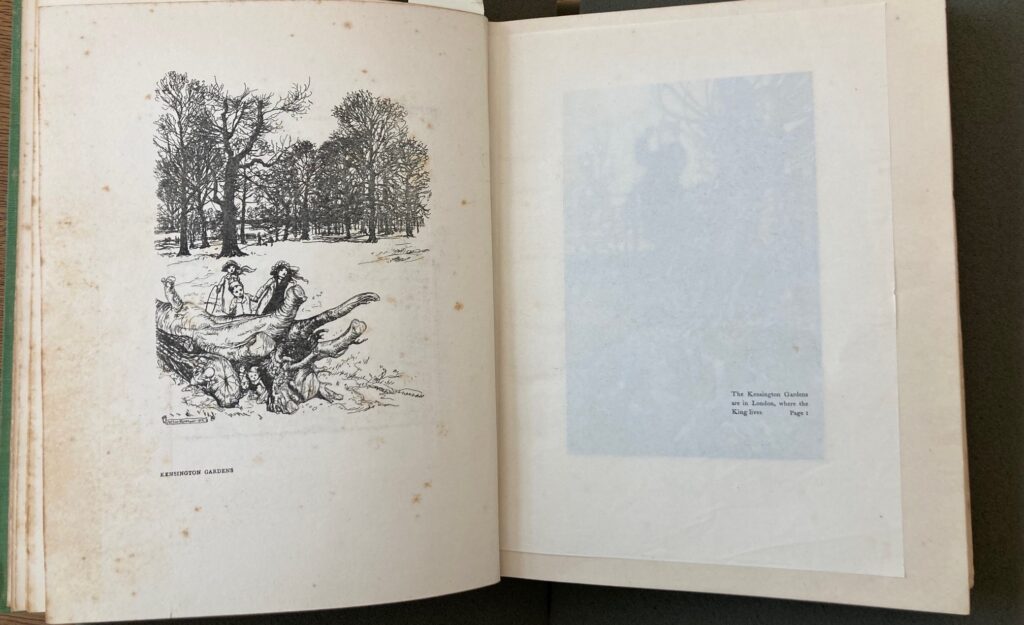

On the other side of the spectrum, there are muted-color illustrations that begin with an experience of unveiling. When you encounter one of these colorful illustration pages, you actually first meet the loose leaf paper on top of it, which has been slid into the codex. These loose pages are tissue-thin and translucent, and some have pressed teeny-tiny captions.

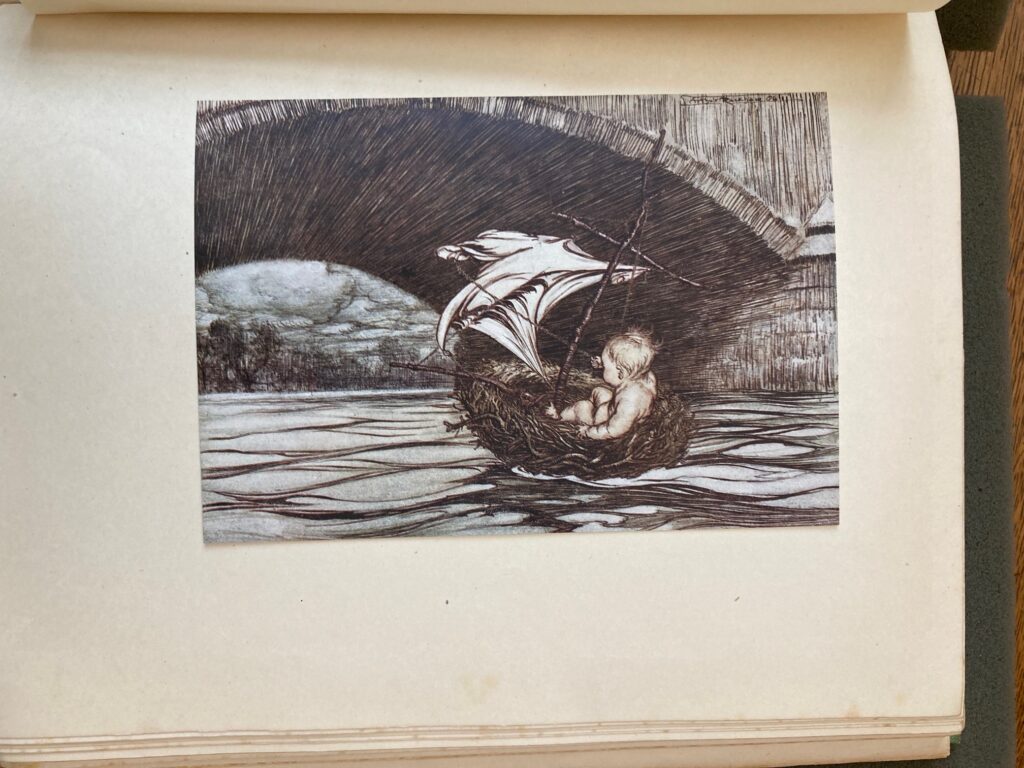

The tissue paper has to be slid out or flipped over to reveal the colorful illustration underneath. Unlike the woodblock prints that are inscribed directly into the codex, these illustrations are printed on a separate paper that has then been pasted to the codex page. This illustration paper is thinner than the codex’s wood-pulp pages, and has a coated surface like a matte photograph. The coating is likely clay, because clay can stick to the other pages when wet, which would explain the tissue paper coverings. Each color-illustration is pasted loosely, with only a line of glue down the leftmost side of the paper; its other edges lift up, popping out in 3-D as you flip through the book.

The texture and looseness makes them feel like makeshift-photographs in a makeshift-photo-album: Peter Pan’s baby book, as it were. The experience of unveiling the illustrations from its tissue-paper-safety similarly gives the impression of unearthing something both intimate and grandiose.

The colorful illustrations evoke magic and mystery through its muted colors and exaggerated shapes. Photographs of these illustrations flatten out the depth of the colors and the intensity of the line-work. The colors are subdued but not flat; there is a water-colory, ombre effect across the landscapes depicted – the textures of nature and clothing are all made of several hues and tones. Looking at these from an arms-length away, the illustrations make for a theatrical display – like stage make-up, meant to be seen all the way in the back row. But upon a closer look, much of the lines in the illustrations were re-traced several times; there is not just one clear outline, but instead a dramatic double-vision of each image that accentuates shadows and movement. The images appear slightly blurry, but enticing. I could imagine someone being hypnotized by the intense level of detail and shadow, drawn to observe each stroke – and each of the spaces between each stroke – to find hidden images and meanings.

Physical Description: [x], 126 pages, 50 unnumbered leaves of plates: illustrations (some color), map; 28.25 cm (octavo)

Signature: a2 A-P7 Q12

Material Description: Cream wove paper with black ink text and illustrations, some color in illustrations. Each plate (except map) consists of mounted colored illustration, accompanied by guard sheet with descriptive letterpress. Original covers, cased in green cloth with gilt engravings. Foxing stains throughout paper and casing. 28.25 cm x 22.25 cm x 4.44 cm. Published 1906 by Charles Scribner’s Sons.