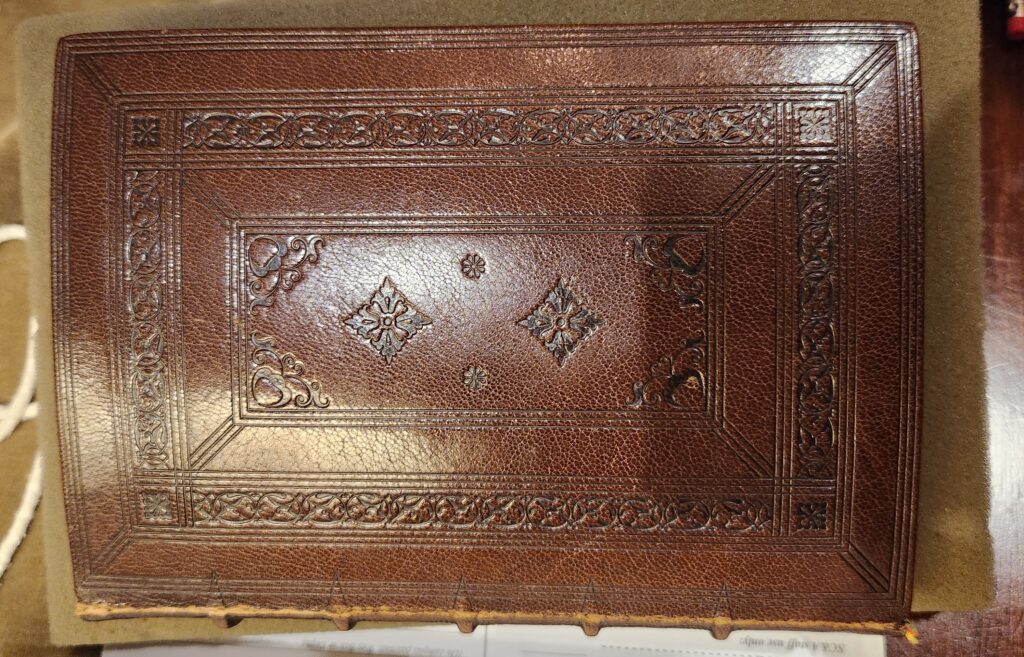

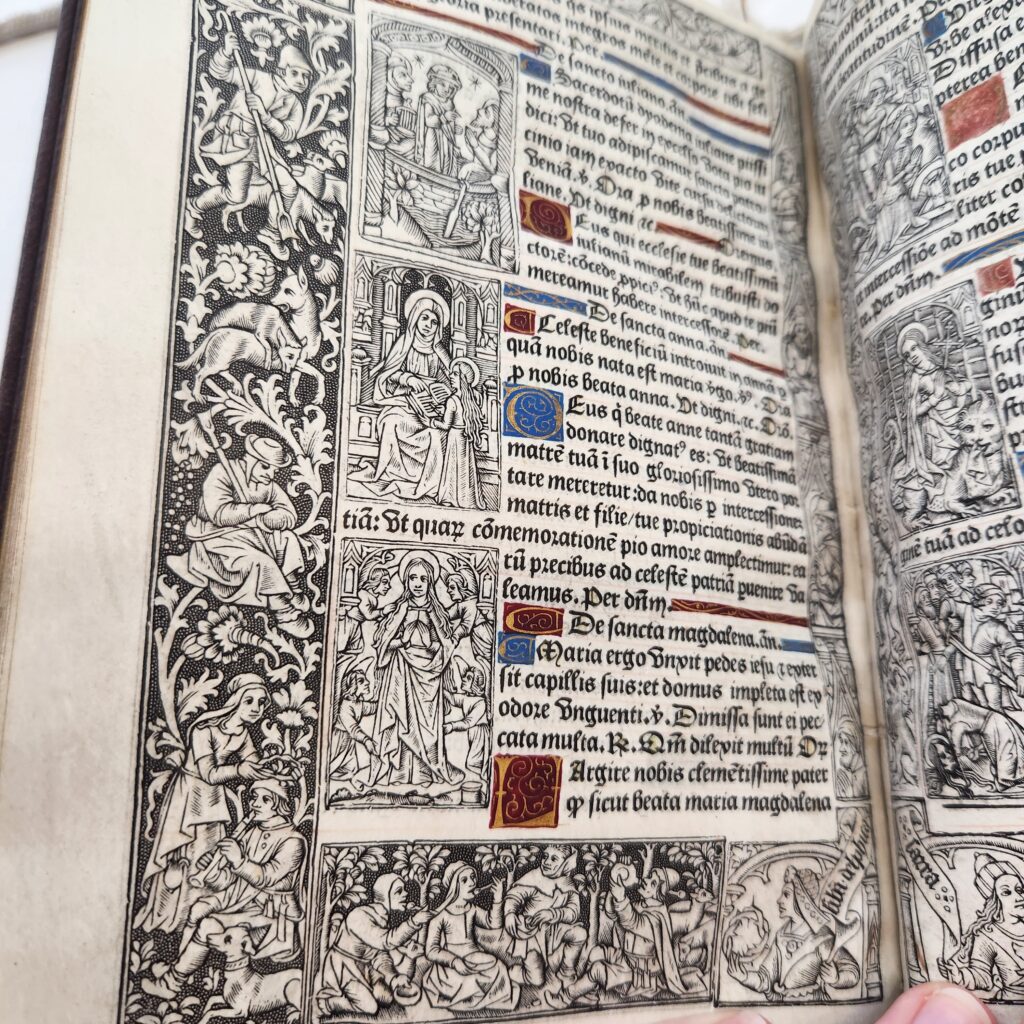

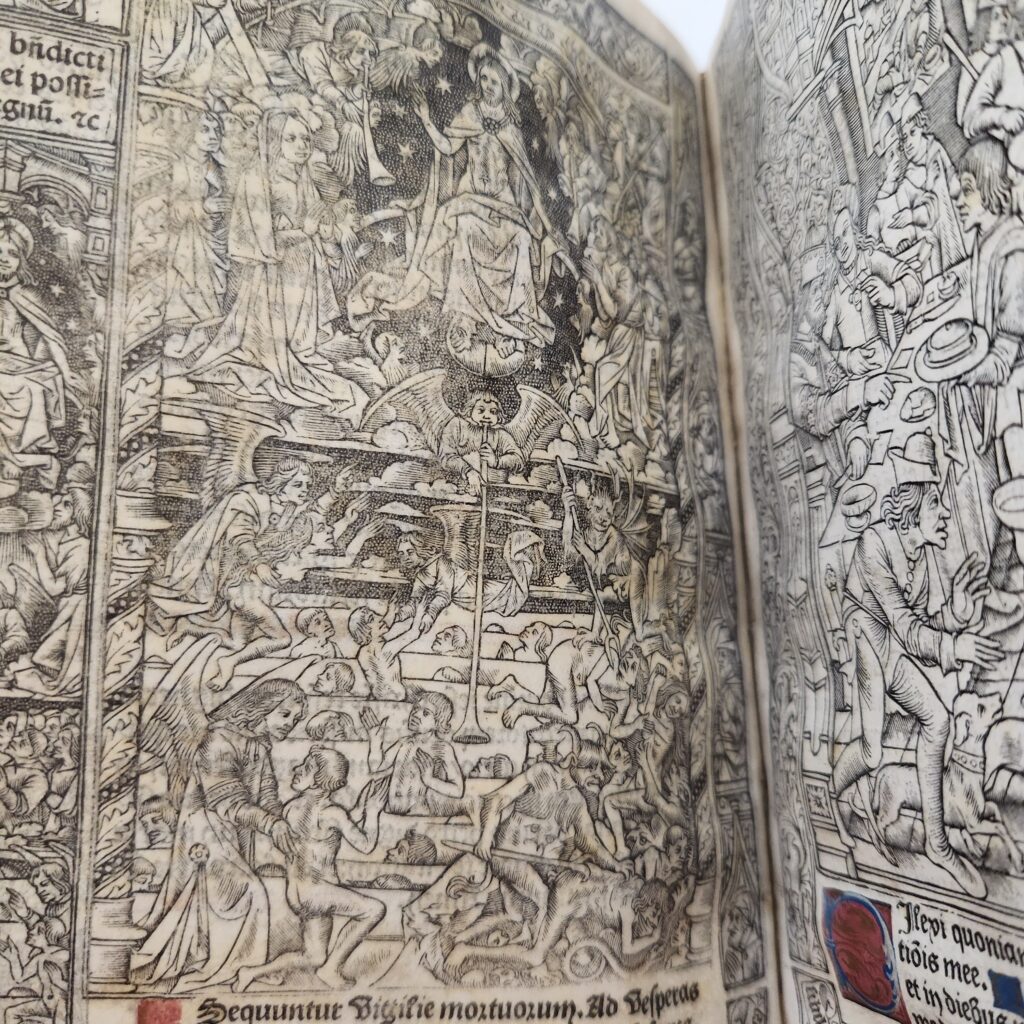

The book that I have decided to adopt is a French Book of Hours from 1498 called “Horae secundum usum Romanae Curiae,” which translates to “Hours according to the custom of the Roman Court,” according to an online translation tool I used. A modern handwritten translation of the title is offered on the first full leaf of the book: “Roman Catholic Church Liturgies and Ritual Hours.” There is also a paper bookplate on the inside cover with an image of a castle or manor; it is a modern addition denoting whose library it belonged to (George W. Davison). This is a stunning book. It is encased in engraved leather and contains intricately detailed border illustrations around the main text; on some leaves, the center text is accompanied or even replaced by a larger-scale illustration which depicted a significant biblical concept or event. The book itself is a “traditional” codex: portable, medium in size, with a very shiny, polished, chestnut-colored cover.

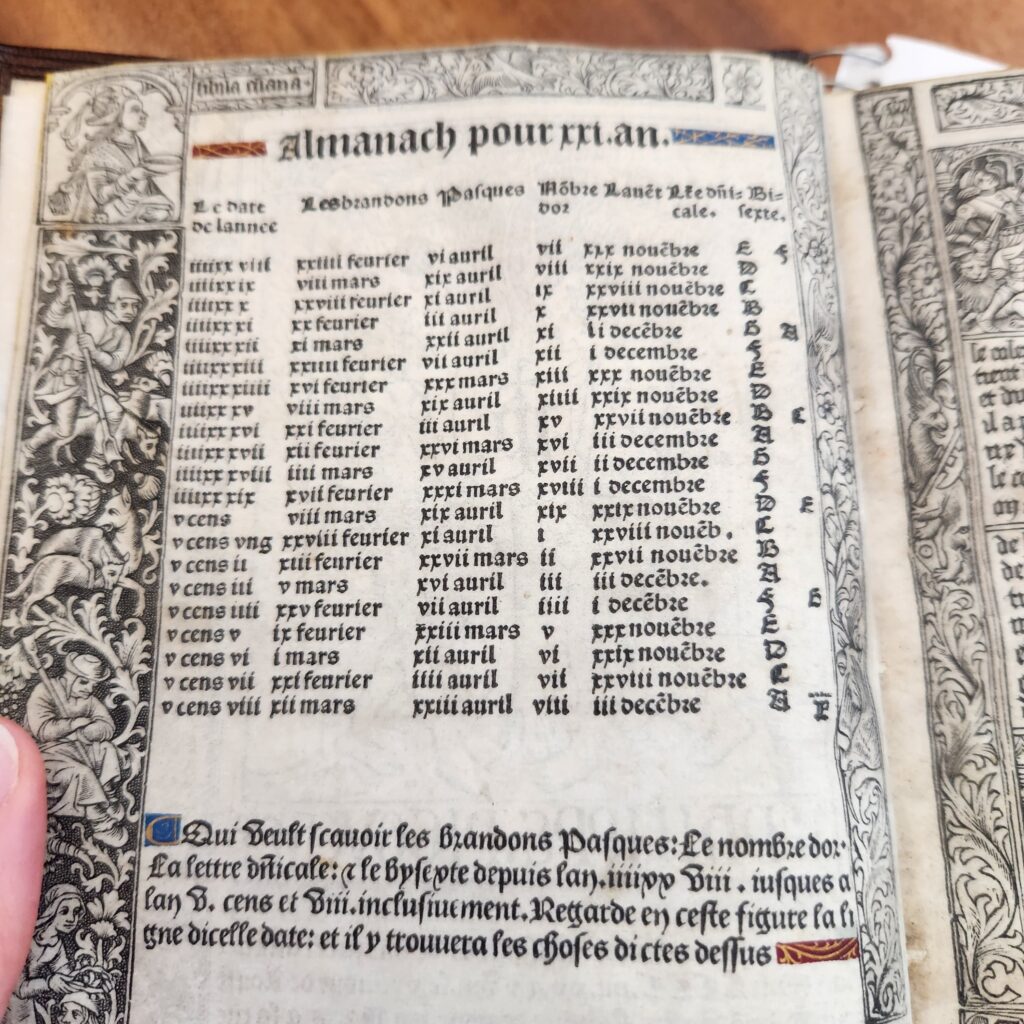

The drawings within are beautiful and, as I mentioned, incredibly intricate. Most are in the panels surrounding the main text of the book. It also contains an almanac which, according to the catalog record, spans the years 1488-1508. This further serves to demonstrate that a book of hours had many applications to its users’ lives though the framework of prayer and ritual From what I understand, Books of Hours often were and still are referred to as “almanacs” based on the structure and guidance they give their readers.

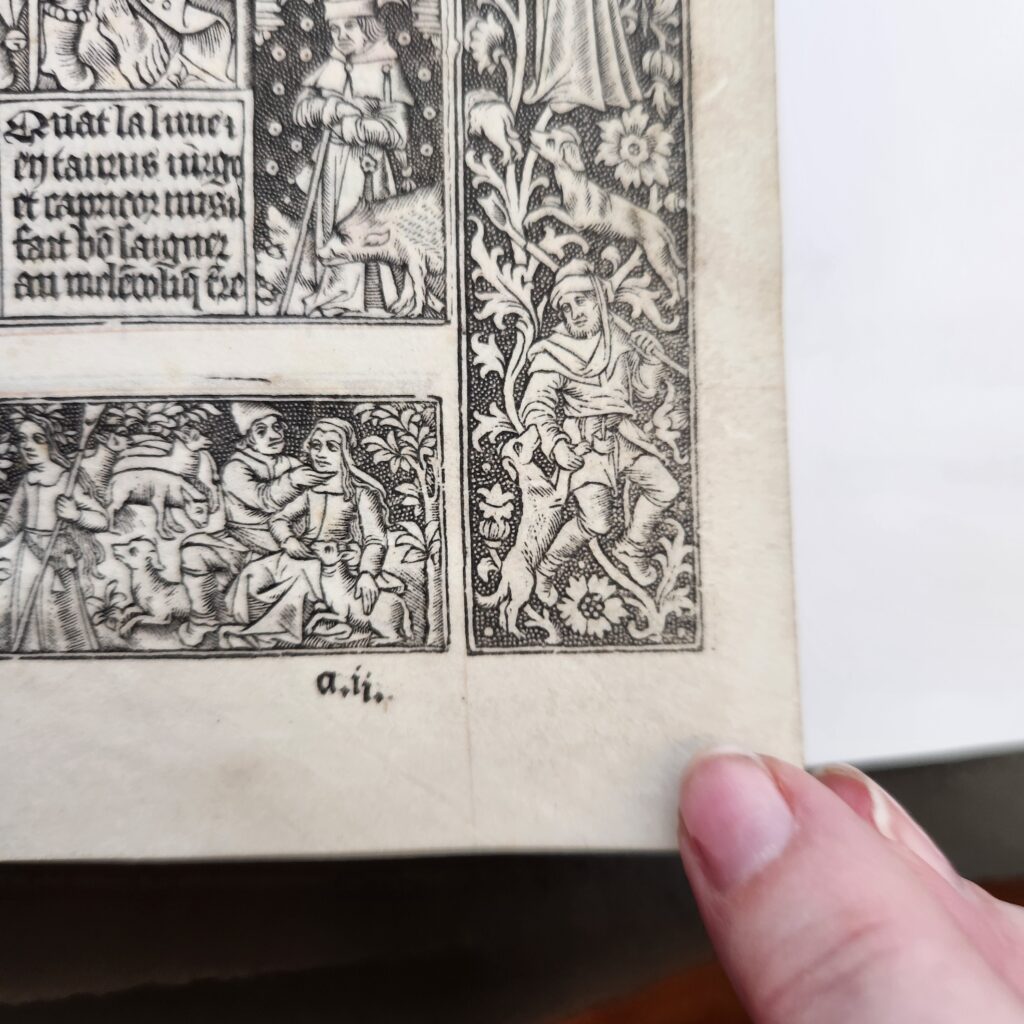

The itself book contains 72 unnumbered leaves and is comprised of 9 quires, which means the leaves were created from one large sheet that was folded into eight parts. This process would have been repeated eight more times and then the resulting quires would have been sewn together. Each leaf measures 13 cm wide by 18.5 cm long. The last leaf of each quire contains a signature on the bottom right-hand side of the leaf; these are written in lower-case Roman letters and numerals.

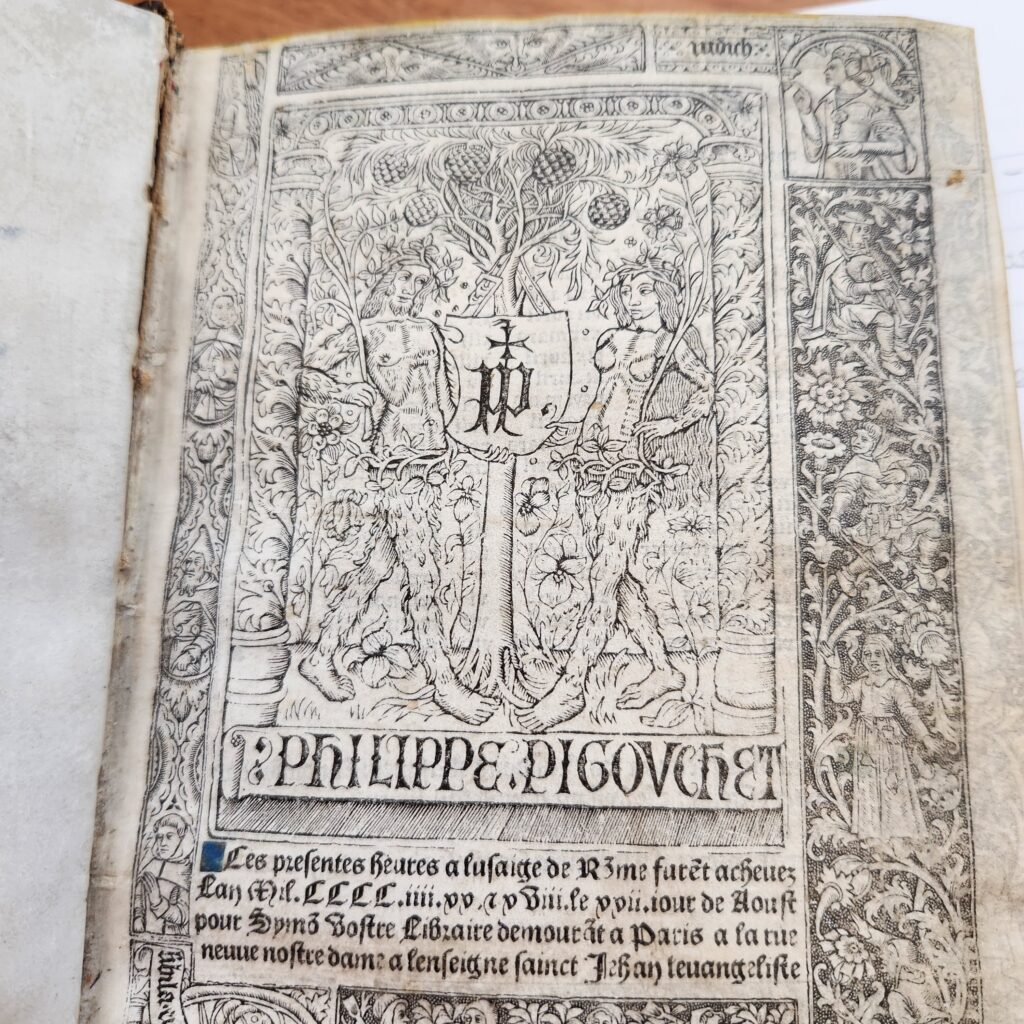

The book’s creator was a French printer named Philippe Pigouchet, who was active from the late 15th century to the early 16th century, and the first engraved leaf of the book displays his name below an illustration of Adam and Eve. Although the official language of the book, according to the catalog record, is Latin, there is a declaration below the illustration that is clearly in French.

Many of the words in the panels appear to be French as well, and the very helpful librarian who assisted me pointed out that although the majority of the text is Latin, the final quire of the book is written entirely in French. I am very excited to learn more about why this might have been. I realize that, as we have learned in class, more prayers books contained vernacular languages than we may have previously assumed, but it is very intriguing to me why only the final “chapter” of the volume was printed entirely in the common tongue. Most of the text on the leaves is black, but there are also many leaves that contain large letters and flourishes in red, blue, and gold ink. The edges of the leaves, though faded, were clearly gilded at one point. Interestingly, none of the illustrations within the book, whether they are in the center of the leaf or part of the side panels, contain color; they are strictly composed in black ink.

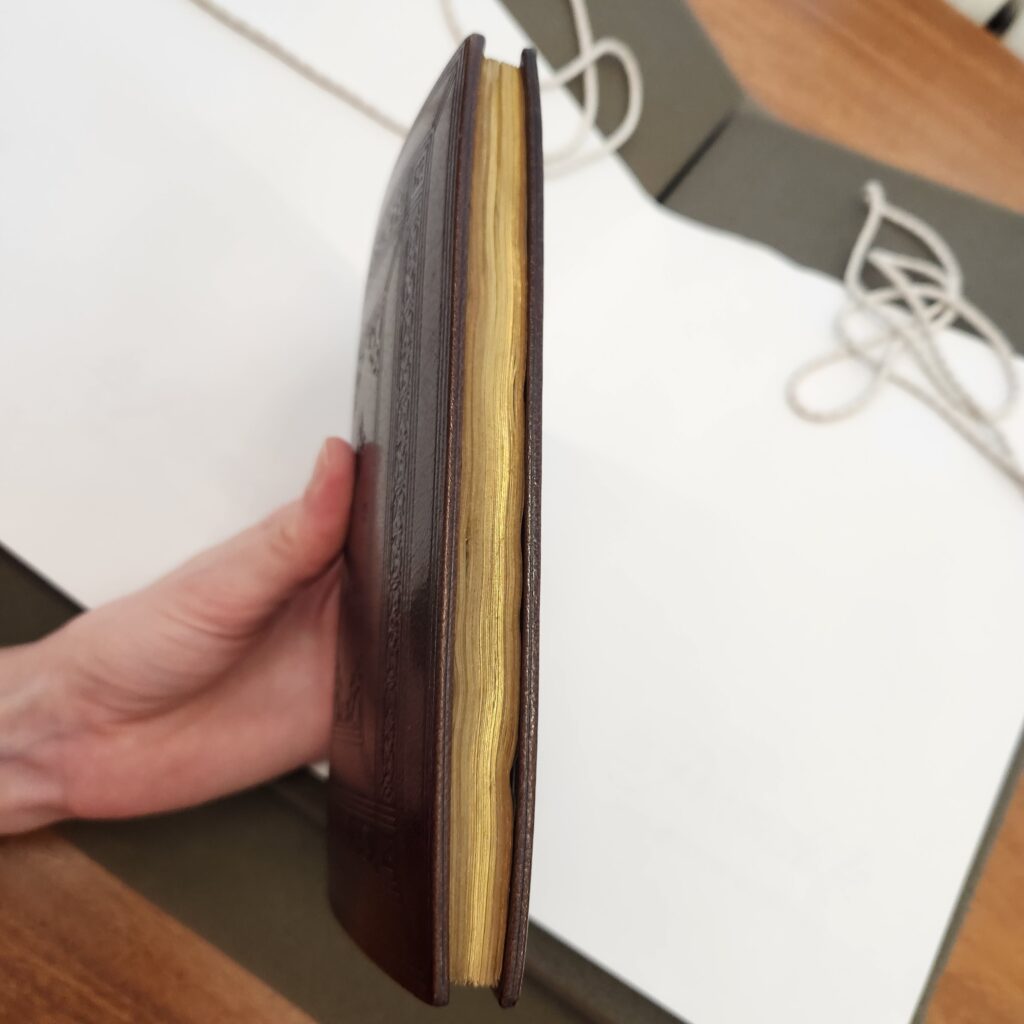

The substrate of the leaves is vellum, according to the catalog record. All leaves are evenly cut and the edges are in line with one another. The leaves are, for the most part, an off-white, “creamy” color. Most of the leaves feel smooth to the touch and even a bit silky, especially along the areas where there is a lot of ink. Some sort of finish must have been applied to make them feel and appear smooth to the touch. However, there are also many leaves that are stained or smudged and are quite a bit darker, and clearly some leaves have a great deal more wear than others. As the picture below demonstrates, there is a yellow color that shows through the leaves whose finish has been worn away. Those leaves have a rougher, almost abrasive feel to them and yet are also slightly softer and more malleable than the better-preserved leaves. Both of these textures are consistent with the National Archives‘ description of parchment and how it would have been made.

All of the leaves within the book have the musty-sweet smell that I have always associated with very old books. The texture, especially of the more degraded leaves, along with the scent and the color(s) are what one might expect of leaves made from preserved flesh; in this case, calf-skin. There are also faint red lines running underneath much of the text and along the sides of the panels; I suspect the printer put them there before anything else was added in order to structure the leaves. They serve to indicate where the text would go and where the panels would begin and end. The text block is sewn together into the endpapers, which are paste-downs on the inner sides of the book’s cover. If you open the book at certain intervals, you can see a bit of the cord which binds the book together peeking through the inner spine.

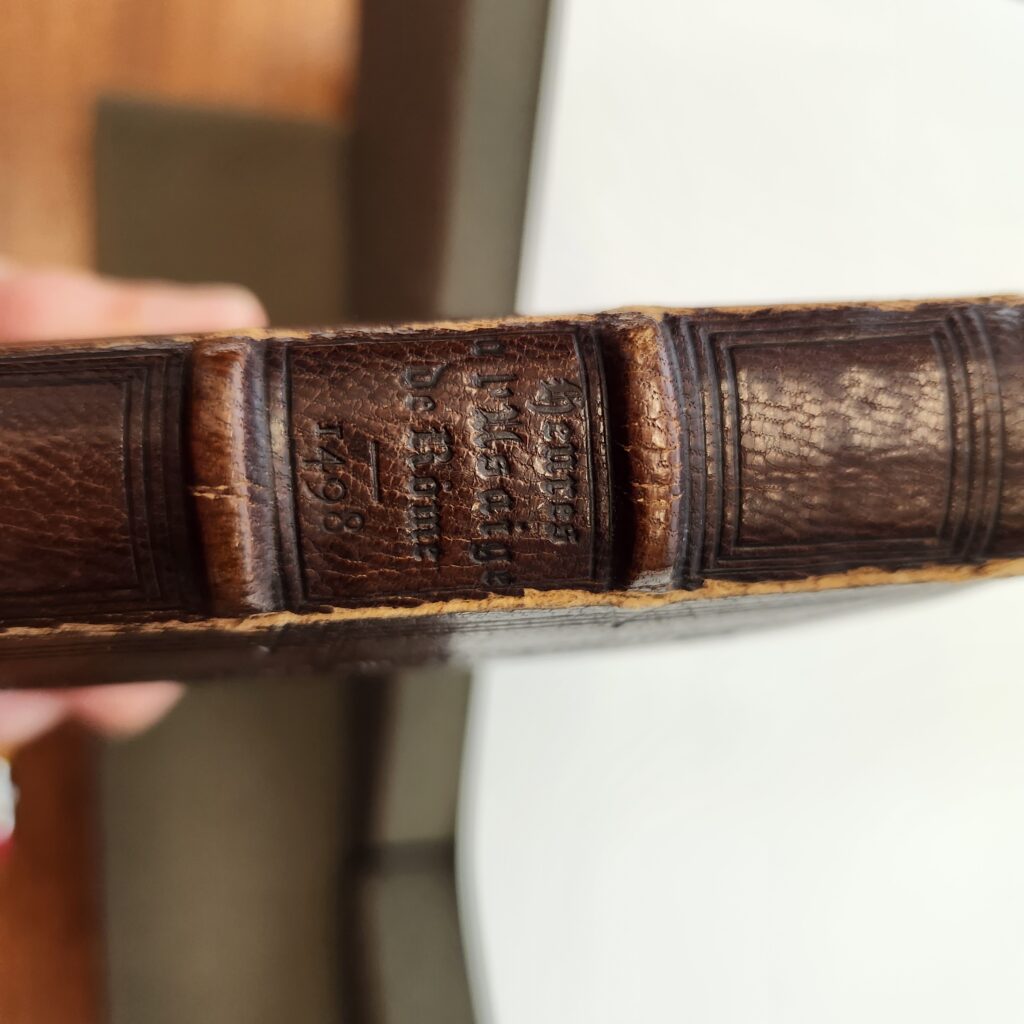

The cover, according to the librarian, was a nineteenth-century replacement of the original cover, which was long gone. The modern cover is made of leather that is engraved with two pairs of four conjoined fleur-de-lis on both sides, indicating its French origins. Unlike the rest of the book, it has no noticeable odor. The spine of the book is particularly interesting. It is about an inch (2.54 cm) in width and bears hubs or ridges all along it which are designed to look like iron clamps holding the book together. Imprinted in black letters near the top of the spine reads the following phrase: “Genres a l’Usaige de Rome 1498.” When I knocked on the cover of the book, it sounded a bit like knocking on a door, and the covers were extremely firm and hard, not bending or yielding. The librarian said that there must be very thin wooden boards encased within the leather that keep it from bending or breaking. As a result, the book is very tightly bound, to the point where it is slightly wider in the middle due to bulging from the strain.

The middle of the book, its bulkiest point, is about 2.5 cm wide when closed, whereas the corners of the book are only about 1.5 cm apart from each other. The cover itself measures 13.5 cm wide and 19 cm long. As the cover is only half a centimeter wider and one centimeter longer than the leaves themselves, this would account for the tightness. It manifests in the spine of the book as well. You can see that the covers are just beginning to crack and split away from the spine at the edges, where there is fraying parchment peeking out from underneath.

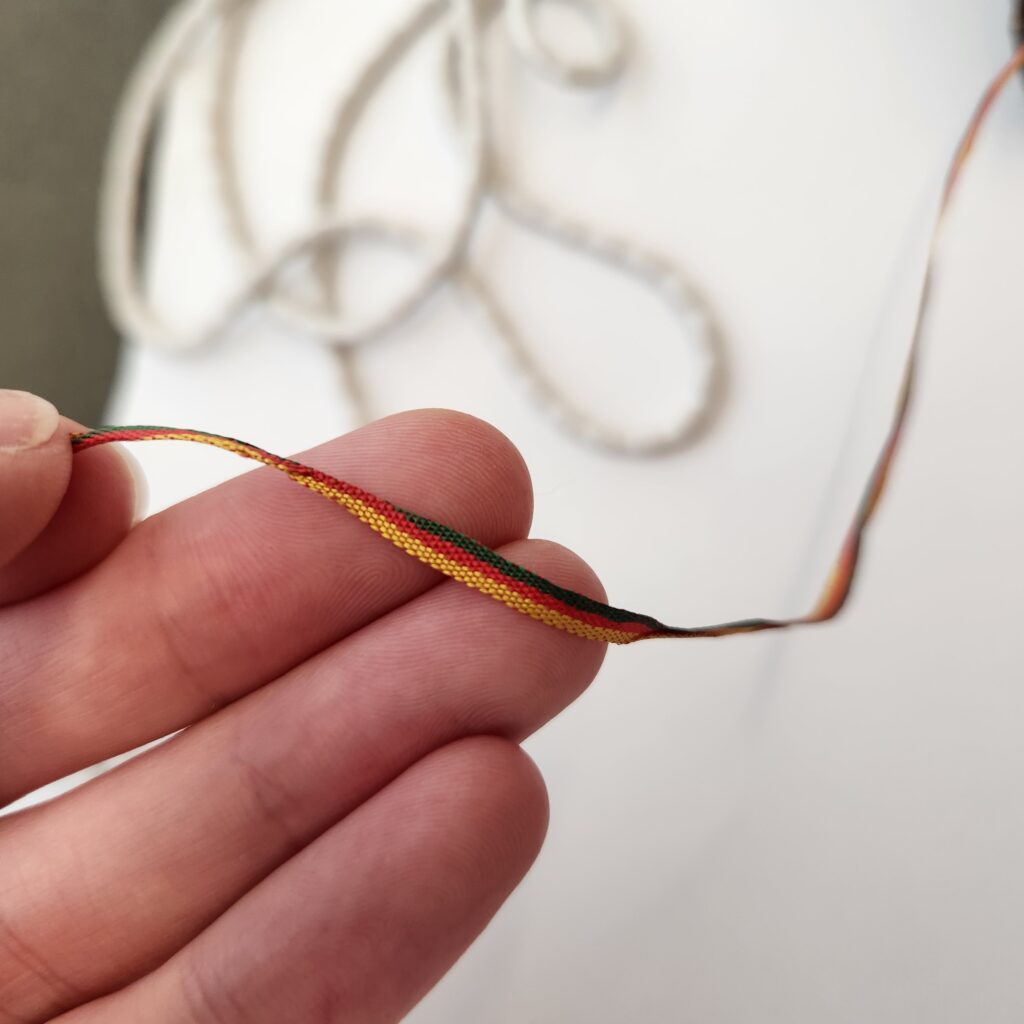

There is also a lovely thin green, red, and yellow ribbon which serves as a bookmark. It is very soft and smooth and appears to be wovern; although it is not accounted for in the catalog record, I think it is made of silk. This would have been added along with the leather cover.

All things considered, what remains of the original book is in remarkably good condition, given that it is five-and-a-quarter centuries old. I cannot wait to explore the illustrations in more depth, and unpack the stories they are telling in dialogue with the text itself.

Physical Description: [ii], LXXII leaves: ill. ; 19 cm. (N.B.: I unfortunately forgot to write down the number of end leaves not included in the quires, so 2 is an estimate based on memory; I will adjust the numbers in my description after my next visit to Special Collections).

Signature Statement: a-i8 with endpapers (again, as I do not know the number of endleaves, I will have to adjust this later and, for the time being, construct my s.s. out of the information I do have).

Material description: Black, green, and red ink and gilt on vellum parchment encased in a chestnut-brown leather cover with black engravings. 19 cm x 13.5 cm x 2.54 cm. Manuscript is sewn into the paste-down endpapers. Some damage to many of the inner leaves, likely from moisture. Leather cover, which is a 19th-century replacement, contains thin wooden boards and bears the fleur-de-lis in several places. A green, red, and yellow silk ribbon is affixed to the inside of the ridged spine. Illustrations of note include an almanac of the years 1488-1508 and an anatomical study of a man’s intestines. First 8 quires are written in Latin with French captions; final quire is entirely in French.