Illustration can be defined widely, but generally is conceived to be something pictorial. A drawing, a sketch, a plate, there are many examples. They are decoration, they are exemplars, they are illumination, they are art. But they are — generally — pictures.

My pet book has only a handful of these traditional images. An initial, a drawing of plants in a vase and another of a peacock. Looking closely, particularly at the cross-hatching, I believe these are relief prints.

All of these images are decorative flourishes found in the introduction and conclusion of the book. They do not appear to have any relation to the text beyond being plant-adjacent.

No pictures or sketches or otherwise presented print images are found in the bulk of the book. Instead there are plant samples collected in a botanical garden, and pressed and glued to the pages. I believe these specimens are intended to illustrate the book.

Specimen Botanicum is meant to be a guide. As ordered by the King, it lists all the plants found in Denmark’s university garden and their various medicinal properties. From what I understand of the introduction and conclusion, Buchwald intended the book to be useful and practical. The samples are included as visual representations. They are dried and pressed and attached to the page and therefore do not precisely resemble the plant one might find in the field. But they provide a model for what to look out for. Therefore they are images.

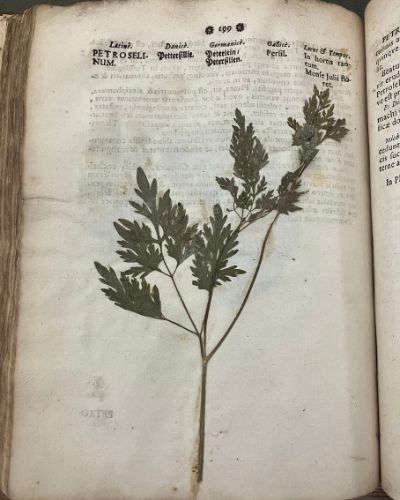

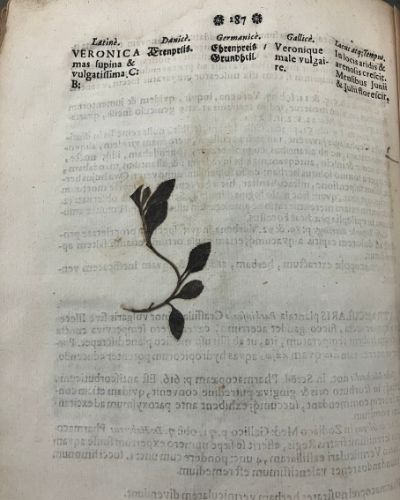

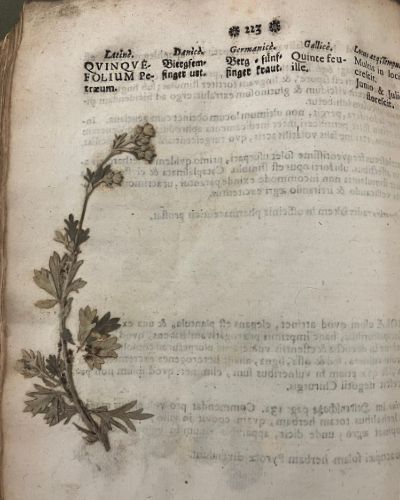

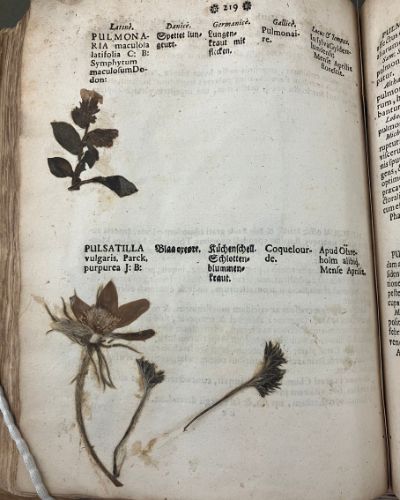

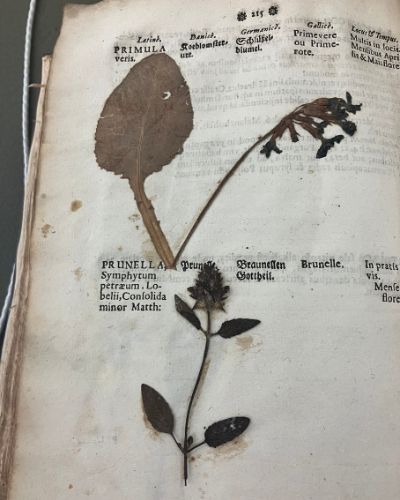

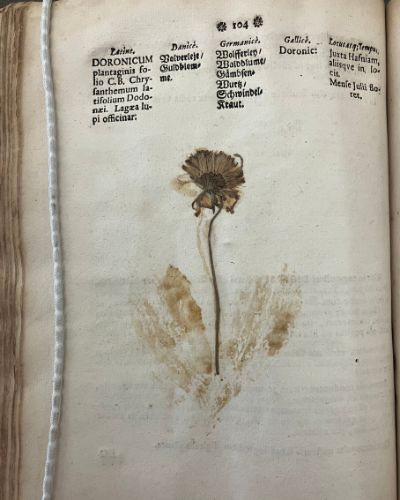

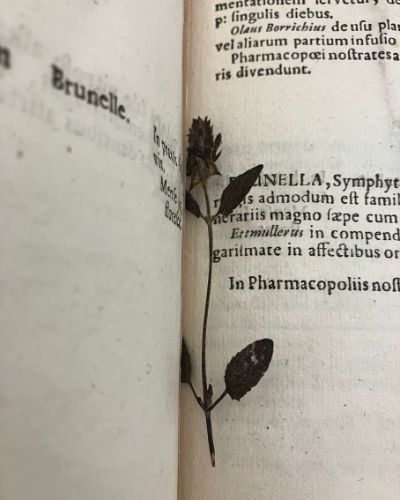

Each plant is pasted beneath its label: the Latin name and its translations and notation for where and when the specimen was retrieved. There is some variety in how the specimens lay on the pages, mainly due to size and structure. Examples are presented below:

Here is an example of a specimen that is placed generally in the center of the page. It spans the whole height, does not overlap any of the text, and the leaves are spread nicely for display. I feel this is one of the most successful illustrations.

This specimen is also placed in the center, but due to its size it does not fill the page. It does have a fun kind of movement to it, however, with the way the leaves and stem are set. It looks playful, like a little plant-puppy.

In this example the specimen is off-center. The placement of the stem, leaves, and flowers is quite lovely, but the page would be more balanced if the image was shifted to the right.

Some entries include two specimens on one page. Here (left) the top specimen is similarly off-center as in the above example. However, the page seems better balanced because it is in line with the lower specimen and that specimen is wider. In this photo you can also see the glue that holds the specimen to the page, and evidence that part of it is missing.

On the right is a close up on the lower specimen, PULSATILLA, that shows off the details of the plant and the paste. I feel this one really captures the beauty of the specimen and the process of preserving it.

In this one, the top specimen is too large for the space allotted to it. The plant overlaps the text. The lower plant also overlaps, though to me it looks like in that case it could be addressed with a small adjustment. This is notable because the image gets in the way of the word. It claims superior significance when in the context of a plant guide the name of the plant is specifically important information.

Finally, perhaps my favorite image. Here the placement is perfectly centered both vertically and horizontally. The leaves of the plant have been lost but the glue shows us exactly where they used to be. I can imagine this specimen being replaced with a drawing, an exemplar sketch that is both picture and plan, and it would look very similar. But I think the effect would be different. The glue outline creates a kind of shadow, a ghost of the flower. It is quite whimsical! Even if the specimen was intact, the texture of it provides another layer of illustration that is lost with traditional images.

There are a number of limitations to using “real” specimens in lieu of “illustrative” images. The plants do not retain their color, shape, texture, or general “liveliness” when dried, pressed, and attached to a page. They are easily damaged. The specimens are not representations of the plant as much as a reference to a one plant that existed within a specific snapshot in time. They are perhaps closer to photographs than to scientific illustrations. But setting aside the empirical intentions of the author, the book is a delight to look at. I do not believe the twigs and petals and paste stains were meant to provide a narrative, but they absolutely do tell a story.