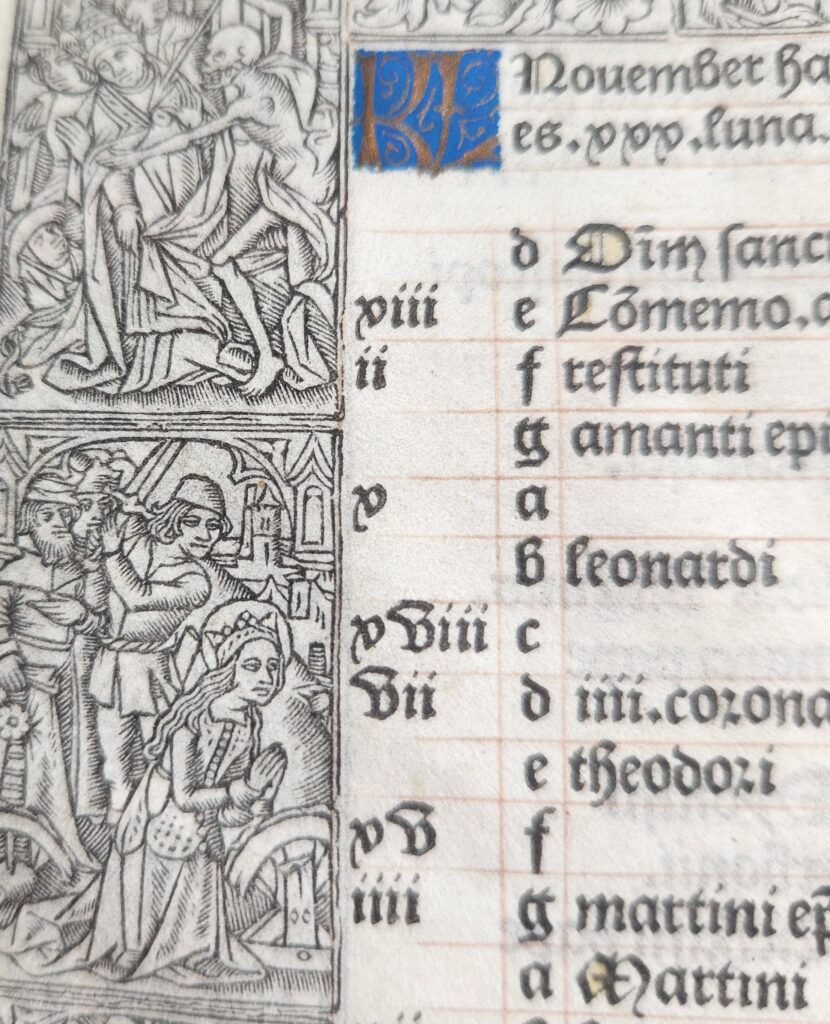

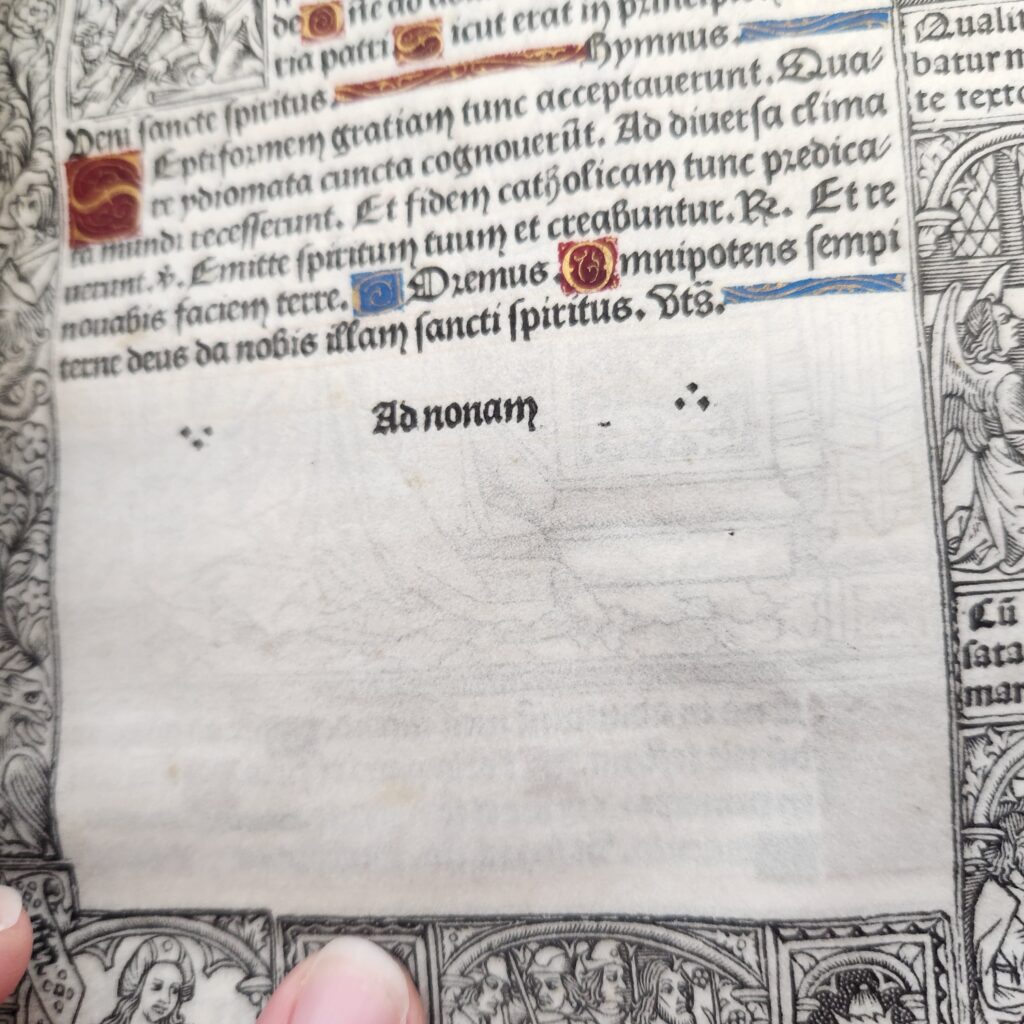

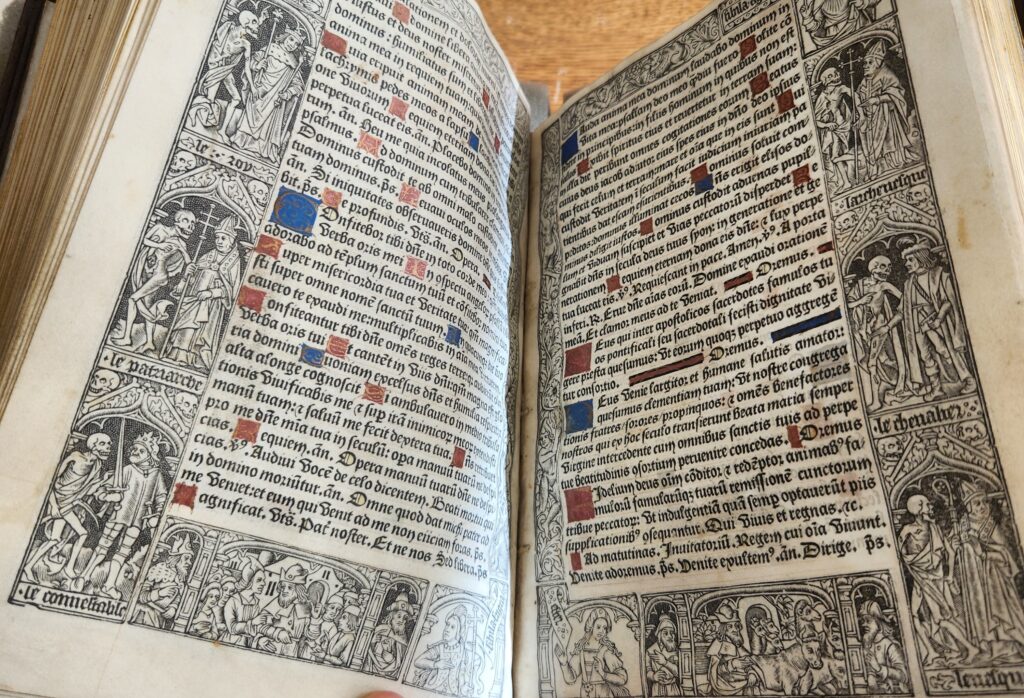

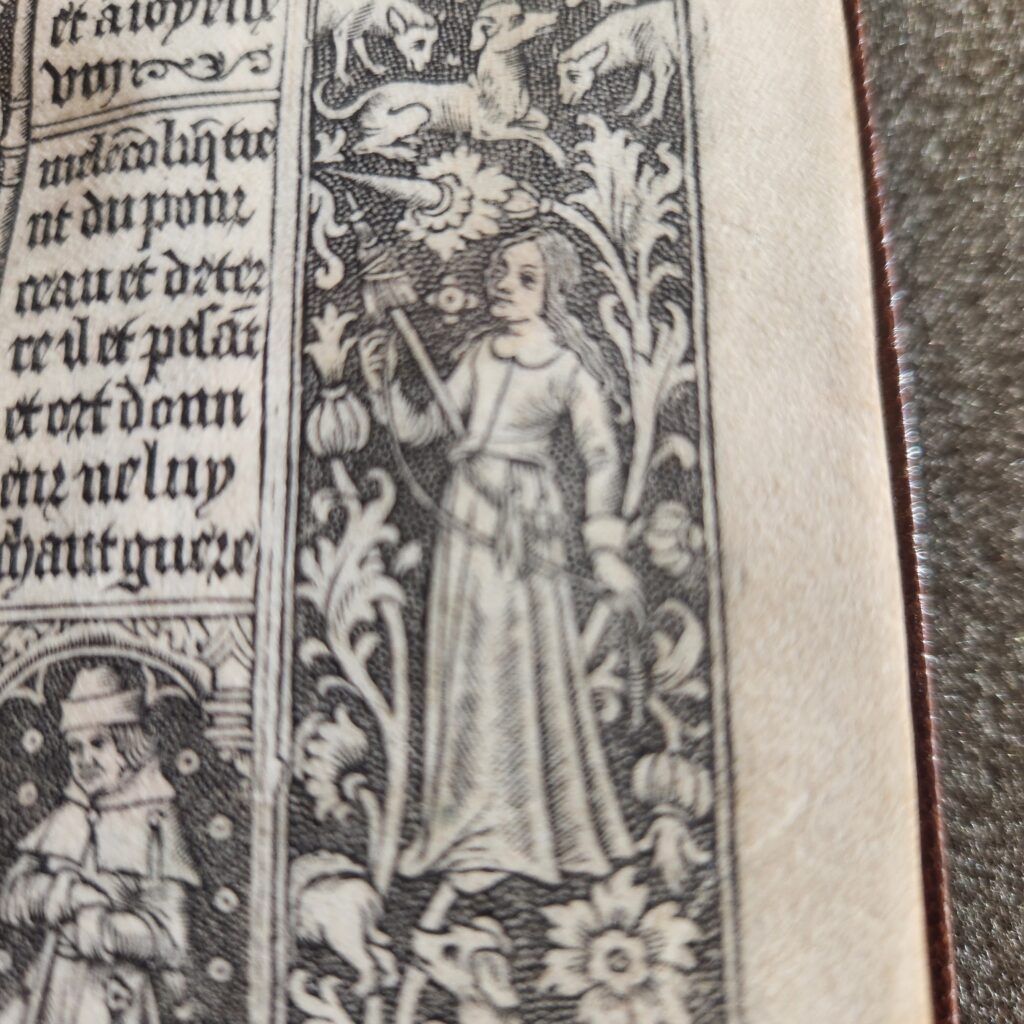

As I covered much of the ground intended for this blog post in my first blog post – the 19th-century replacement cover, the damage done to the inner pages, the degradation of the spine, etc. – I’ve decided to focus instead on the more abstract version of the afterlife for my pet book, beginning with its origins. While I know that this book of hours belonged to George W. Davison, a rare book collector and Wesleyan alumnus, in the early twentieth century, its first owner was likely also its creator, the late 15th-century French printer Philippe Pigouchet. As it seems to have been a manuscript, based on the red rubrication lines and the empty spaces left on several of the pages where names, inscriptions, or other personal touches might have gone, Pigouchet probably kept it to use as a template for other books of hours.

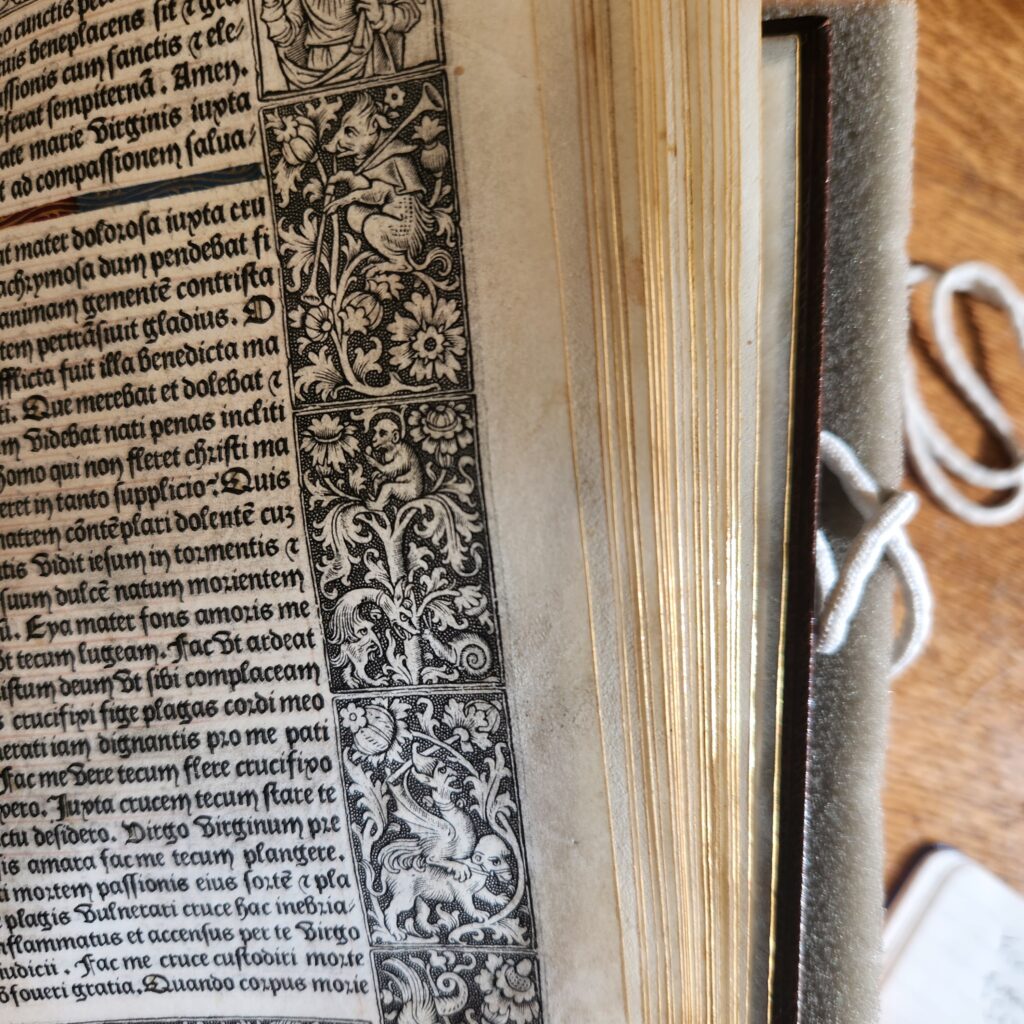

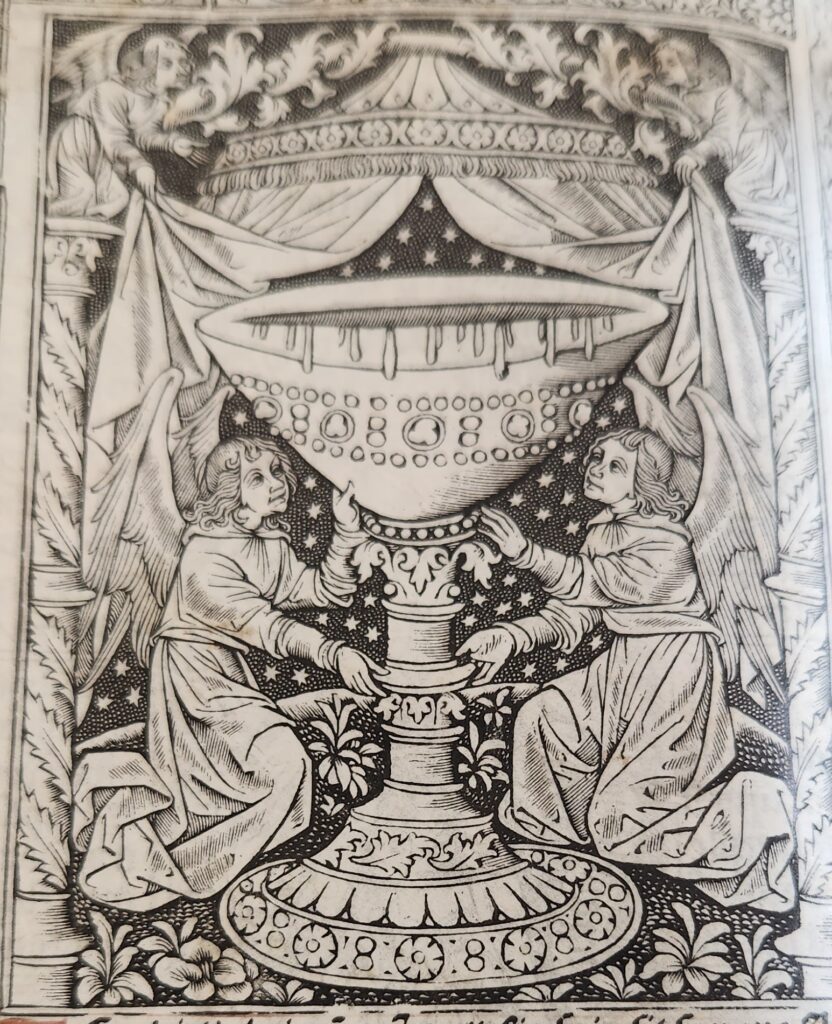

I suspect that while it was still in its first life, it was used primarily by the printers and their successors rather than purchased by an individual for private consumption. However, the audience that books of this ilk were intended for would certainly have been affluent, possibly members of the French bourgeoisie, perhaps even noble. Given a book of hours’ close association with women’s roles, the primary owner might very likely have been female as well. This prayer book relates to its audience as a social body by the very fact that only the wealthy classes would have even known how to read, or had the disposable income to own such a volume. This item was not just a votive object or a repository of information; it was a status symbol. It reminds the original reader of its value through its stunningly intricate illustrations and gorgeous text as well as the gilded edges of its pages. This was a luxury commodity!

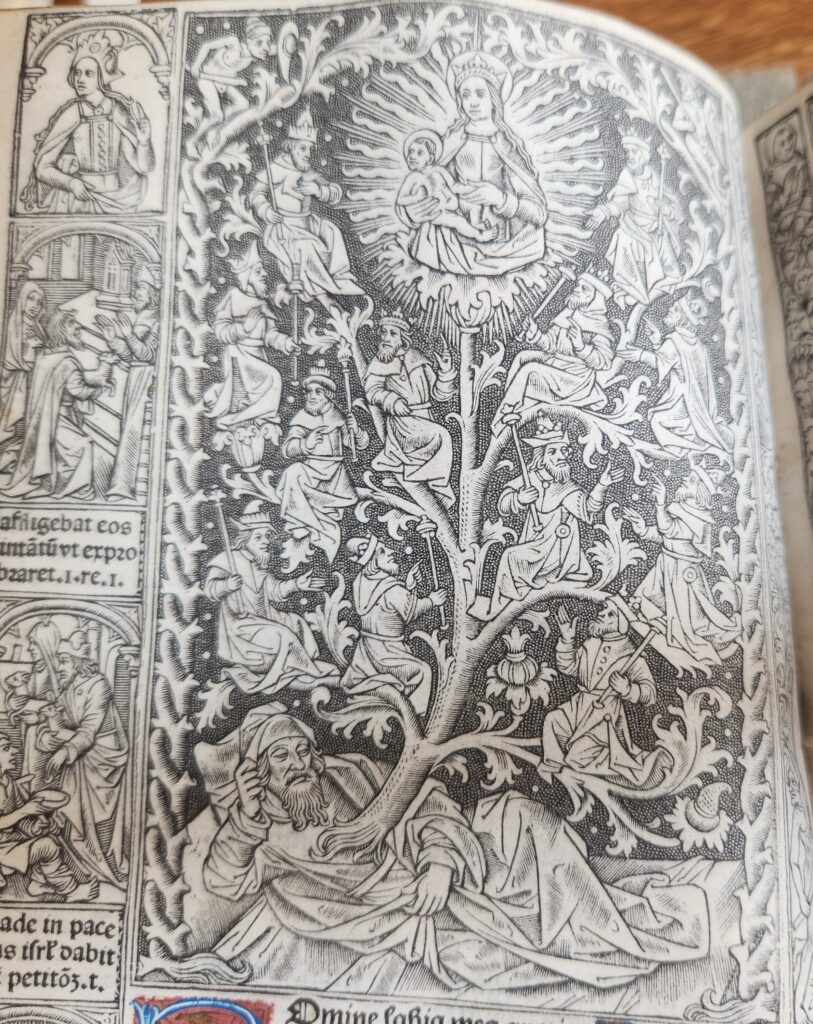

However, it did not exist to inspire decadence; quite to the contrary, its role was to impose a strict regimen of prayer and piety on its keepers. It instructed its owner on what time of day to pray, how many times, which prayers to say when, and when to observe feasts, saints’ days, and other major religious occurrences. Additionally, it would have instructed them on how to live their lives. A book of hours is a vessel for the Word of God, or at least significant swaths of it, and so it would have imposed daily rules on its readers of how to conduct themselves in keeping with divine ordinance. The book of hours remakes the reader in its own image much the same way the Christian God made Man in His image: it takes a profane, unenlightened being and transforms them into a dutiful follower of Christ with discipline, structure, and knowledge of the Holy Word; or, at the very least, that is what it aspires to do. It assumes the reader is a practicing Christian of the educated class who wishes to live what would have been considered a godly life. The images participate in this process by reminding the viewer of the suffering experienced by the saints, then by Jesus, then by more saints as well as some sinners, and finally the suffering of the readers themselves, as they are reminded that death ultimately comes for everyone.

This constant depiction of suffering reinforces that life, for the original reader, would have been nasty, brutish, and short, that their only hope for peace and comfort lay in achieving salvation and thus Paradise, and that prayer, abnegation and austerity were the keys to this. Therefore, the only escape from suffering was through more suffering.

As goes without saying, I am not the original reader. I look at this book as a relic, not as a source of authority or holy wisdom. My experience of it is archaeological, not spiritual, and I interact with it in a much more analytical way than its earliest readers would have. This book gives us a snapshot of what life was like for the wealthier classes in early 16th-century France; what it could not tell its original audience is how much that would differ from the lives of every generation that came between them and us. It tells us a bit about what Christianity looked like on the eve of Reformation, right before things would change forever for the Catholic Church. It is, in a sense, a time capsule, one that has preserved a shred of an era which we will never see again. I can ask it what other spiritual traditions influenced its artwork, and how its illustrations shaped both the religious and the secular book art that would come after it. I can ask it how religious texts and, with them, people’s personal beliefs evolved after its heyday and how our relationships to these texts began to change with them. I can also ask it where it stood in the history of literacy: how it compares to educational tools of later eras and what each text tells us about who had access to readership. Most intriguingly, I can ask it what it can tell us about women’s lives, their roles both as students and as educators and how it shaped their understanding of the wider world as that began to change as well. It is the root of a tree that branches out into each of those stories and, from my perch from the top, I can see at least some of the answers.

I could see this book being housed in a museum or a religious house as a cultural artifact. It could also be used by scholars to compare translations of the text in different languages, as it is in both French and Latin. However, its most fascinating feature (in my opinion) are its images. I can imagine it being purchased by a rare book collector or used by an artist to create new marginalia inspired by illustrations that came centuries before, perhaps to illuminate a graphic novel or as part of a Monty Python-esque animation sequence that takes once-sacred images and turns them into (very funny) parodies of themselves.

However, in a post-human world, I do not know what role it would play. I like to think of Jan Brett creatures making a home out of it; that would be a much happier fate for it than being devoured or simply getting subsumed by nature. On the other hand, an intelligent alien species might treat it not entirely unlike the way we do. They might be able to recognize it as a relic of a civilization gone by, even if they cannot understand its original function, and thus preserve it as a sort of curiosity. It is a beautiful object that invites speculation and scrutiny, and I think an alien community that wished to understand whatever life form came before them would find it intriguing. I think they might be able to at least recognize that it was a document of some sort, a way of communicating information, even if they have no deeper context for it than that. I wonder if they would be able to tell that there was a functional distinction between the images that made up the text and the images that made up the illustrations, and that the illustrations on the pages were meant to portray the life forms that preceded them.

Most of all, I wonder if they would be able to surmise that it was a relic not only for them but for us as well; something that was made by the species that came before them but not by its most recent iteration. I hope they would treat it as a sort of fossil and take it apart in a lab (or whatever they have) while keeping its disparate parts intact so as to study them. They could learn a great deal about us from the materials we used to create it and from the figures on the pages, if they can deduce that those are indeed self-representations. They might even be able to tell that certain parts of the book were from different periods of time than others, and thus infer that it was actively preserved, rehabilitated, and cared for by the species that created it over the course of centuries. I think that would unlock a great deal of information for them about its original purpose and with it, a window into who we were as people.