By all accounts my pet book was the pet project of a well connected professor of medicine with an interest in botany. Johannes de Buchwald apprenticed as a barber, trained as a surgeon, and became the first doctor with practical experience to teach at the University of Copenhagen medical school. He initially worked as Crown Prince Fredrik IV’s personal physician. When he ascended the throne Fredrik elevated Buchwald to “royal life physician” and later installed him as a professor, chancellor, and councilor at the university. Due to his “keen interest in botany” he was put in charge of the Botanical Garden and embarked on both redesigning it and cataloging it. (The Great Danish & Harvard Library)

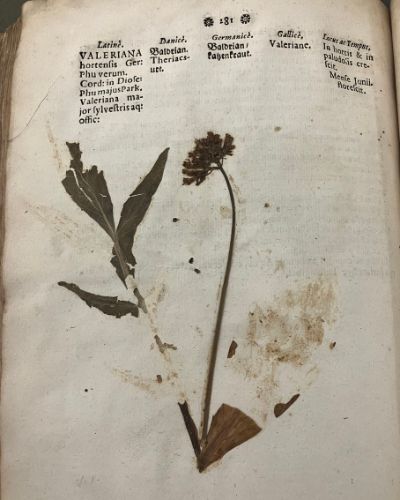

“The work first appeared with Latin text in 1720 and the year after in German translation, by his son [Balthasar Johannes de Buchwald]. Both versions appeared both with and without the original plants, thus also as a mere printed catalogue. And copies vary.”

Lynge & Son datasheet (Harvard Library)

By design Specimen Botanicum begins its afterlife immediately upon publication. Though some copies remained empty of specimens, all were invited to contain them. And regardless of intent, each one was by necessity unique because no one plant could be pasted into two or more books.

“Buchwald seems to have been particularly interested in botany, but what he has achieved in this direction, a large work with dried plants in it, has been criticized very sharply and shows that his knowledge in this area has been quite lacking.”

Lynge & Son datasheet (Harvard Library)

I do love shade launched over hundreds of years! But all this is to say the author had one vision for the book and it barely achieved that, if at all. Its afterlife — or really its life entire — is something wholly different from that vision. Specimen Botanicum, and specifically the copy that I adopted and interacted with over the past few months, is not at all informative about plants. Any botanical or medicinal information it may contain is irrelevant to modern science. But the book has become a curiosity, a snapshot of history, and a work of art.

The plant specimens in my pet book are three hundred years old! The Special Collections librarian and I fully geeked out about it. It is also exciting to interact with a book so old, but flowers are ephemeral.

The plants were once living and now cling to that life in very interesting ways. They are pasted into the book— a process that leaves a mark, changes both page and plant. In some instances the paste has dulled with time and the plants have come loose, falling between the pages or out of the book entirely.

Sometimes fragments remain, other times just the suggestion that something once was there. But each piece, intact, partial, missing, or something in between all three, tells a story. A story separate from the author’s intent, separate from the information attached to it, separate even from the book as a physical object.

My pet book changes every time I open it. Which leads me to consider how that may be true about every book. A book may be picked up by anyone, not just the intended audience. As society evolves so does our perception of text, image, space, and how they interact with each other and with the audience. The same perceptions change as we grow individually, too. Wear and tear is not always as obvious as it is in a book that contains dried plants or a book that is hundreds of years old, but it happens to even the most protected items. My photos, or Harvard’s digital scan, could live on should the book itself disappear. If they were printed and bound they would recreate the catalog, but it would be a totally different version. Books are not static objects and from my perspective “afterlife” is an unnecessary category until such time as the book is transformed into something demonstrably new, such as a pile of ash after burning. And even then I am not entirely convinced.

The book lives.