Pet Book Blog Post# 4 – Before & After-life

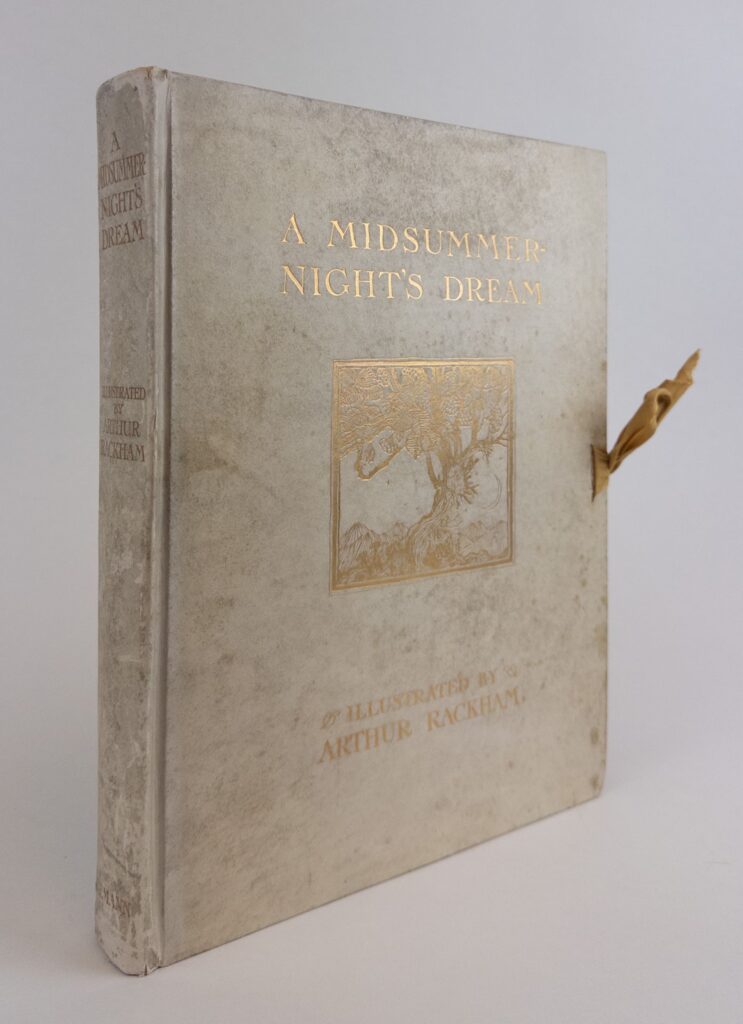

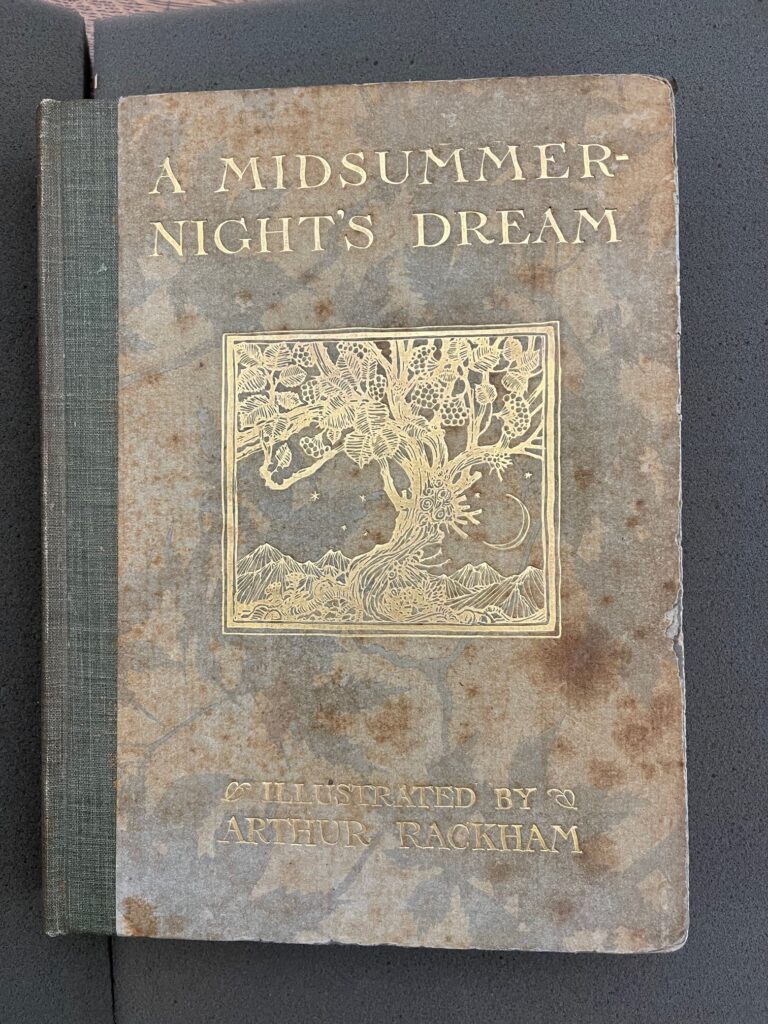

A Midsummer’s Night Dream by William Shakespeare with Illustrations by Arthur Rackham. London, Heinemann ; New York, Doubleday, Page & Co., 1908

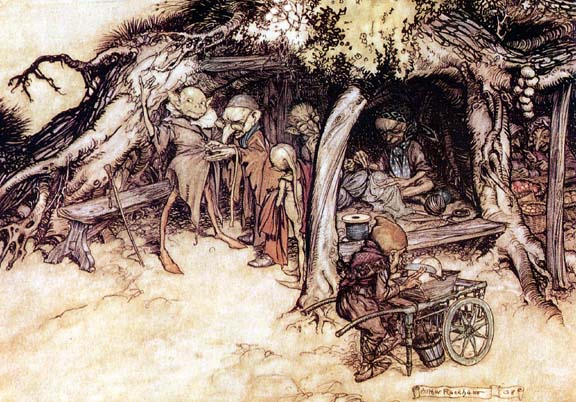

While many illustrated editions of individual plays have been created: Arthur Rackhams’ 1908 edition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream may be the most widely known and iconic of all interpretations, inspiring countless theatrical productions (as seen below, Glyndebourne 2023).

“Rackham cast his spell over the play: his drawings superseded the work of all his predecessors…his gnarled trees and droves of fairies have represented the visual reality of the play for thousands of readers.” Derek Hudson.

Before I consider my Pet Book in terms of it’s ‘after-life’, we must consider it’s ‘before-life’.

Simply, what was the motivation for the publishing house to produce this illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s play.

Founder of Heinemann Publishing House, London

As Victorian society became more literate, publishers sought to create and sell sophisticated printed literary works with illustrations. The publisher William Heinemann surley saw this collaboration as a win-win opportunity, to both capitalize on Rackham’s immense popularity and the constant demand for illustrated editions of Shakespeare’s plays. Heinemann released both a vellum bound deluxe limited edition to be purchased by adults as a sign of status or culture and a mass marketed cloth bound trade copy (which my pet book is one of). I can imagine these found their way into the middle-upper class homes of Victorian Britain to be read by adults and children alike.

Heinemann’s investment in Rackham was a success, as described by the designer William de Morgan as, “the most splendid illustrated work of the century’.

By March 1909, three months after it’s publication, the entire deluxe edition of 1000 copies had been sold out, and of the 15,000 trade copies, 7,650 had been sold.

So, what was it about Rackham’s illustrations that made this edition so popular? According

to Rackham biographer James Hamilton, “Rackham brought a renewed sense of excitement to book illustration that coincided with the rapid developments in printing technology in the early twentieth century. Working with subtle color and wiry line, he exploited the growing strengths of commercial printing to create imagery and characterizations that reinvigorated children’s literature, electrified young

readers, and dominated the art of book illustration at the start of a new century.”

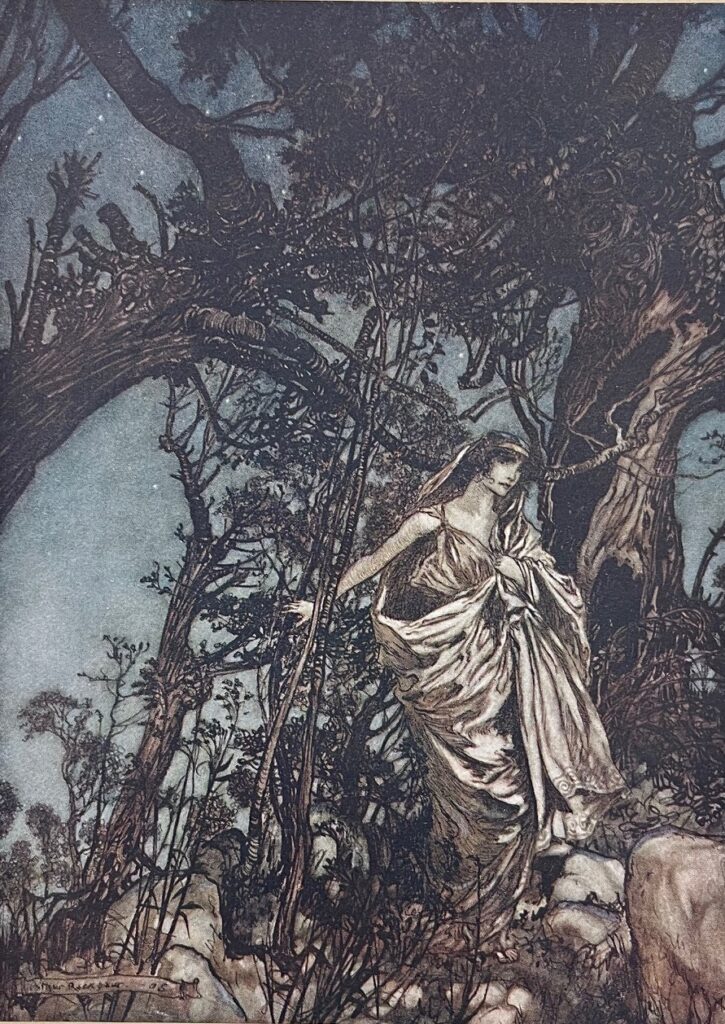

The Victorian reader would have been enchanted by this dreamy and romantic interpretation of Shakespeare’s magical tale. As literature often provides an artist the avenue to let go of reality and plunge into the depths of imagination, his pages are filled with drawings of frightening humanistic looming trees and sensuous yet chaste maidens and fairies. And strange unique characters which are ugly enough to repulse yet not frighten. Rackham’s illustrations played with light and color to achieve haunting effects and conveyed a non-threatening yet fearful thrill and beauty, which was both reassuring to children and the adults.

The play’s whimsical story itself set between fantasy and reality would have greatly appealed to the Victorian reader. As illustrated children’s literature took off from the 1870s, their nostalgic fascination with folklore and fairy culture helped promote the idea of childhood as a time of innocence. Rackham illustrations preserved a more traditional lifestyle and sensibility that kept the grey and dismal industrial future at bay. As Stuart Sillars has observed, illustrated editions of Shakespeare’s work reveals how “the plays, increasingly seen as the vital embodiment of cultural maturity, are absorbed into changing ways of seeing, and of organizing and aestheticizing knowledge.”

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Arthur Rackham

As mentioned in my previous post which explored the word/image dynamic of my pet book, the picture is quite vehemently favored over text. Heinemann’s intention was less to pay homage to the admired playwright than to celebrate the artistic contributions of a popular illustrator. As Rackham noted he considered these books to be ‘portfolios’, where his artwork was as important as the printed word. In this vein of thought, publisher used Shakespeare’s text as a vehicle for commercial success and the illustrator used it as a tool for artistic experimentation.

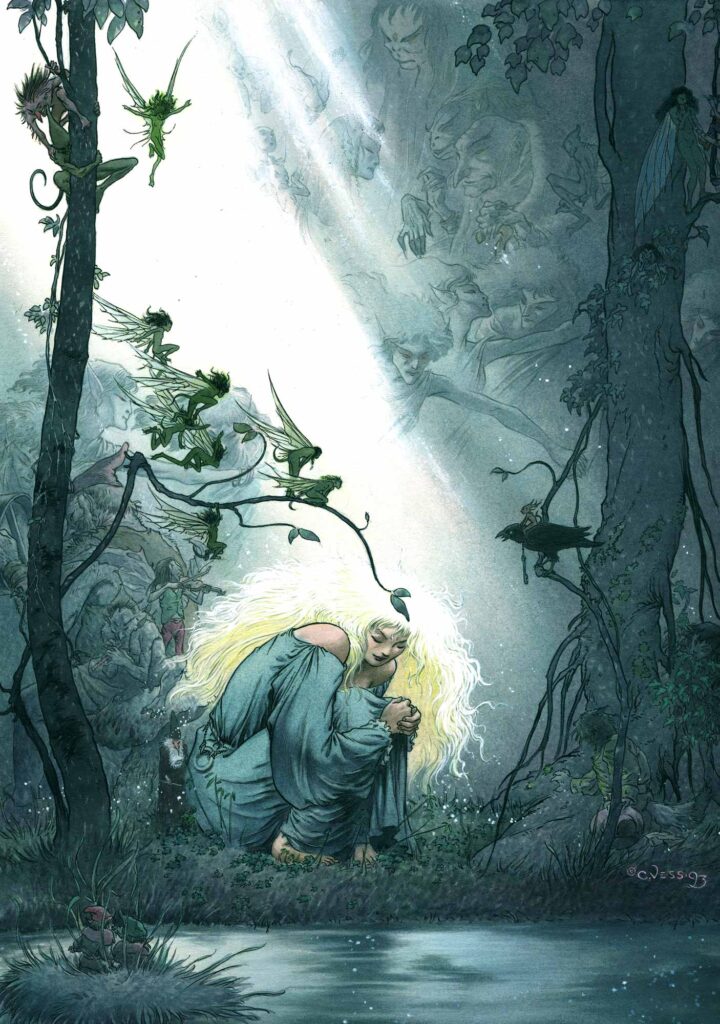

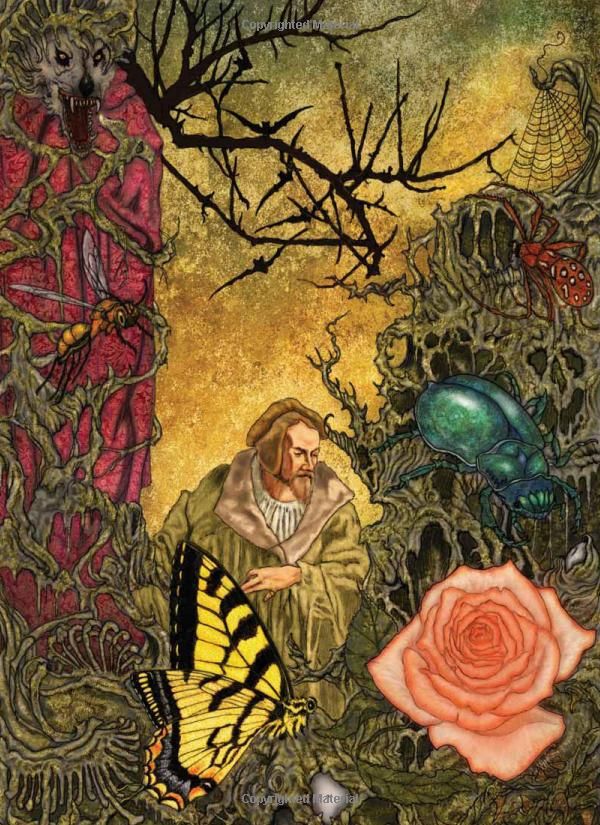

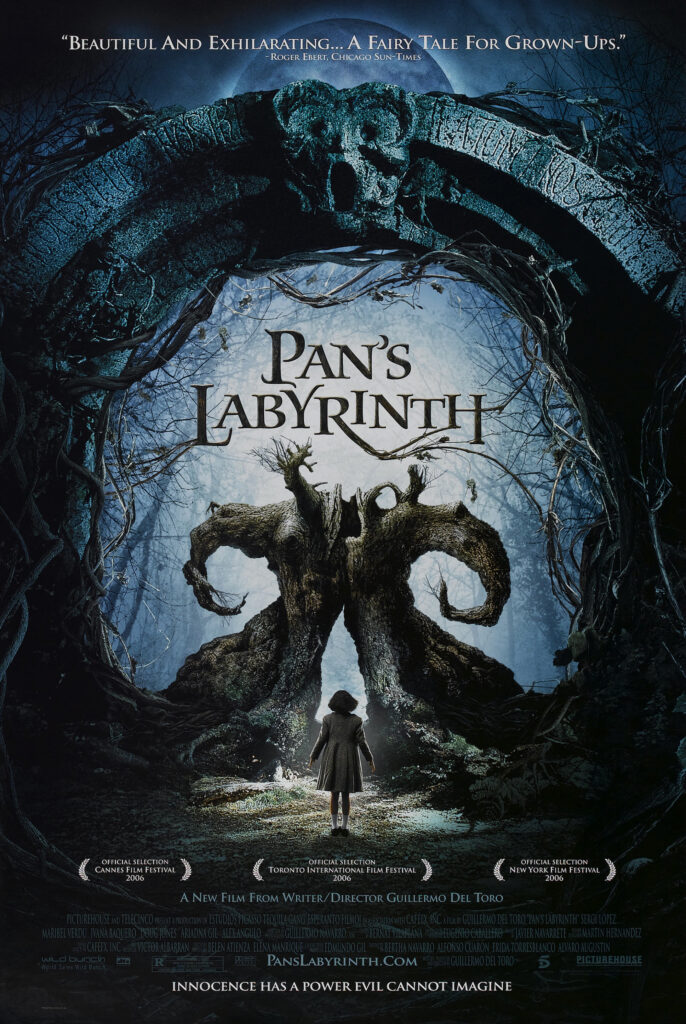

As I wrap up this final blog post I must reflect on the enduring legacy of Rackham’s work. His impact and influence on generations of fantasy and science fiction artists is clearly visible today. The after-life of his contribution to the field of illustration can be seen in present day to influence modern day illustrators including Charles Vess and Michael Hague and referenced in fantasy films such as The Lord of the Rings and Pan’s Labyrinth.

A Midsummer NIght’s Dream, Arthur Rackham

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Arthur Rackham

The beauty of Rackham’s illustrations is in the balance between fantasy and reality, which as you can above transcends all forms of art. I believe that fairy tales will continue to feed our imagination and help break down boundaries of time and culture and remain a constant reminder of those aspects of innocence that have been left behind. In my opinion the combination of Shakespeare’s timeless writing and Rackham’s evocative illustrations make this pet book a classic treasure and one which will remain relevant in picture book history. And in it’s Afterlife, long may it continue to bring new generations of readers imaginations to life.

‘So far be distant; and, good night sweet friend:Thy love ne’er alter till thy sweet life end!’

Folios and the Unessay

Before I sign off from my final blog post you may recall in the very first installment I attempted to record how many folios were in this codex. After numerous visits to Wesleyan’s Special Collections Library to figure this out, I still remain unconfident in my estimate. Either way I think this speaks to the uniqueness of this pet book and the fact that Rackham’s portfolio approach of illustrating the text of Shakespeare’s play, has created a complicated subversive union of word and image within a codex structure. This concept of how the illustrator has attempted to weave his visual interpretation of the story into the book form is one which I will explore further in my Unessay…