“… Most of you are probably not the intended reader for your pet book. Those working on children’s books are not children themselves …”

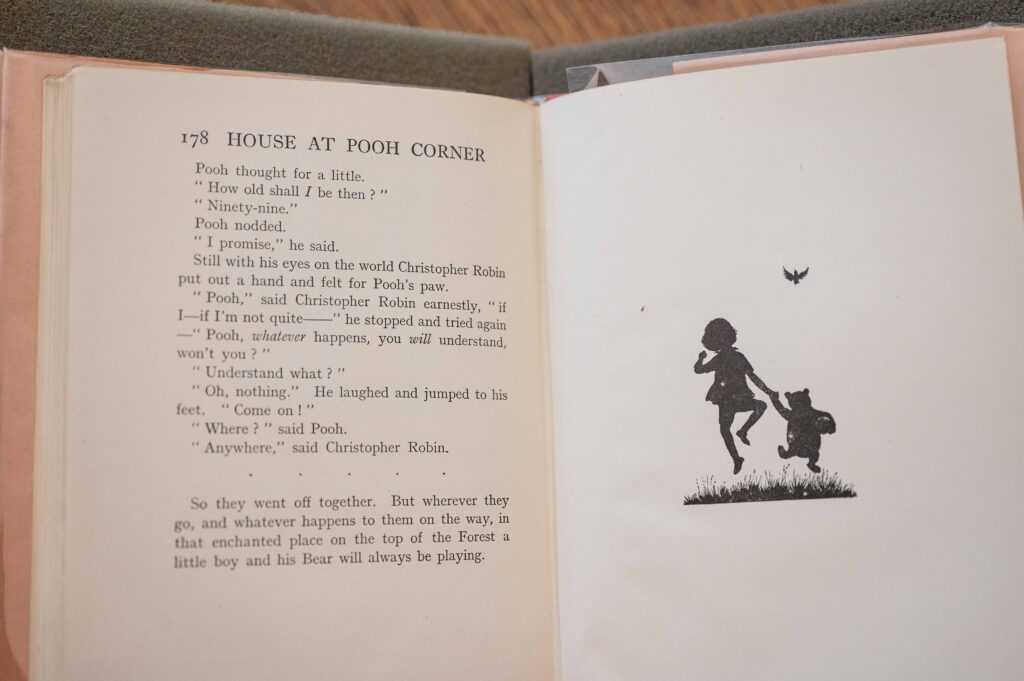

Oh, but I am the intended reader of The House at Pooh Corner — and I have been since 1960, when I turned four and the book was first read to me at bedtimes by my father, right through this year, 2023, when I read from the book to my five-year-old grandson, William, one sunny late-November afternoon before we played with his fabulous Brio train set.

It is this continuity — a stretch of years and ages and developmental stages — that makes this book (the title, not the copy) what it has been for me for some 65 years. It was priceless in the home in which I grew up: a tidy four-room apartment perched on the second floor of a brick building on the waterfront campus of the college where my father taught engineering while my mother traveled to a nearby town to teach preschool.

I remember the experience I had as a child of hearing this book as clearly as I remember the aroma of Dean Urban’s pipe tobacco that infused the faculty wing at Webb Institute of Naval Architecture in Glen Cove, N.Y., where I dutifully served my childhood as a member of the 1960s North American (Northeast) privileged white middle class.

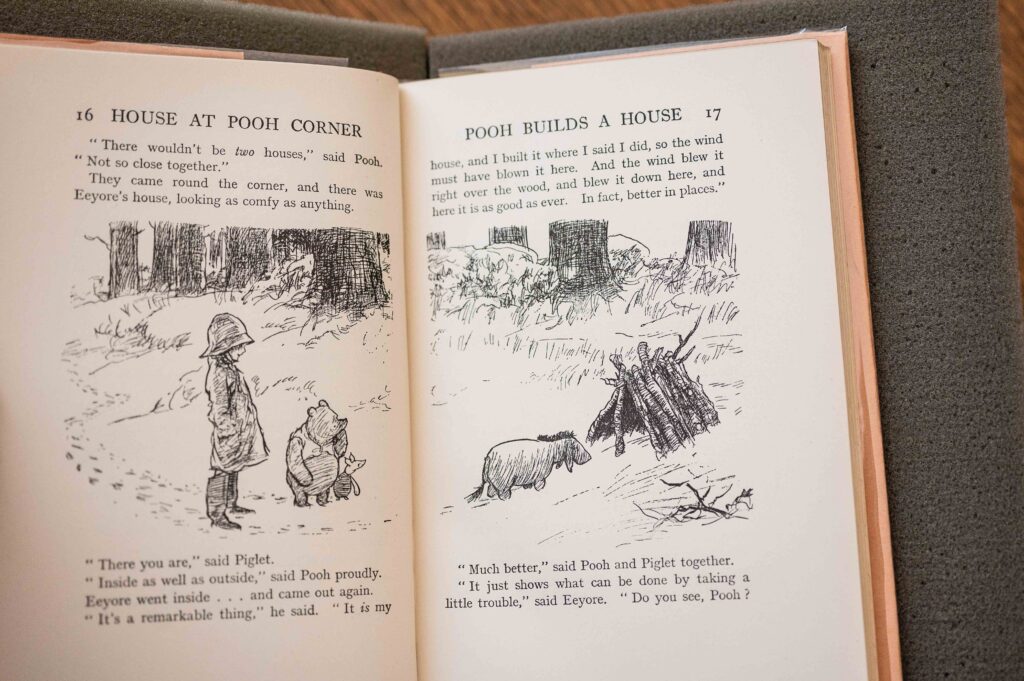

The copy of Pooh Corner I have been writing about this semester dates to 1928 and was owned by George W. Davison, according to the bookplate on the opening endpaper, probably from its publication on. How he used the book is not known, but there are clues. It is in excellent condition: the binding is notably solid, the pages are not foxed or torn or dog-eared, the cover is not warped or stained or toned or faded, the dust jacket — a rarity for any 95-year-old volume — is nearly perfect, without even the tears or compression that happen when people pull a book off the shelf using one finger at the top of the spine. All of this leads me to the sad conclusion that Mr. Davison’s copy was essentially unused — or was used only cautiously.

Which is a shame.

My own copy of this book — from 1959, the 140th printing, according to the copyright page — is tattered, like the decades-old bear it tells about. The binding is breaking apart (the front cover hangs onto the text block by threads), it’s written in (my mother added my name to the opening endpaper, in pencil, and my sister wrote her name in red marker across the title page), and the dust jacket is probably now just dust.

If a book is an object “to be well read” (and many are exactly that), Mr. Davison’s copy may have failed to live up to expectations. If a book is something to be owned and stored safely on a shelf in a cool, darkened library, saved for future generations to admire on foam platforms in secure, cool, darkened rooms, then it has excelled.

I mentioned the culture I grew up in: white, not affluent but lacking almost nothing in terms of personal safety or comfort, we lived in an elite academic community. Both my parents were “properly” educated (both regularly read the New York Times and watched Walter Cronkite, and my mother actually owned a copy of “Emily Post” and hosted cocktail parties), and although they worked, they were home in the evenings to prepare (and share) nutritious meals and enjoy leisurely reads with their only son (at the time), born the year the successful launch of the Russian Sputnik satellite terrified the American public. (Remember, the Cold War was in full regalia; we had atom bomb drills at school.)

This book — the title, if not the actual copy — was an adjunct to that life, reflected and endorsed and supported that life (Milne’s tone as narrator and Shepard’s as illustrator exude the “elite” and “white” of a certain London culture that had no distractions from politics or other races or ethnicities, along with the enchantment that plugs into that culture).

Despite all that, the book still has “legs” in 2023. According to “The Smithsonian,” “The original Pooh is amazingly still alive, well into the 21st-century, in both literary and animated forms.” From “The Washington Post”: the Pooh books have never been out of print, “have sold about 20 million copies and [have] been translated into more than 50 languages.” Including Latin.

But Pooh Corner has also been replaced (at least for my grandson) by Spidie and his Friends (available as board books, as single-story softcovers, and as chapter books, not to mention as videos on demand on Youtube). Pooh himself has been replaced (in my grandson’s Middletown home) by a stuffed “Slothy.” (The home’s actual bears are safely stored in a closet.)

Still, in my Broad Street apartment, my own copy of Pooh Corner occupies a place of honor on the top shelf of a bookcase stuffed with books saved from my and my three daughters’ childhoods.

And in Olin Library’s Special Collections & Archives, the book is still treasured, along with a 13th-century Paris Bible (on aromatic parchment) and Jill Timm’s Talking Rocks: New Mexico Petroglyphs. In the model established by Mr. Davison, and followed by the SC&A staff, The House at Pooh Corner is well protected from age and clumsy childhood hands (and red markers), standing by, ready to serve another generation or two, even if from a respectable distance.