My PET book is, according to World Cat, held in 23 libraries. Most are in the United States, 10 are in New England, PA, NY, and Mid-Atlantic state liberal arts colleges; 5 are in major southern state universities and 3 in CA; one in Illinois, as well as one at the library of Congress. There are 2 library copies outside the U.S.: one in London, The British Library, St. Pancras; and one in New Zealand, the Aukland Libraries. So out of 55 copies, it seems Chevington Press may have as many as 32 copies, although I find no listing anywhere of private collections that may own the book instead of being in his inventory. Many of the books on D. R. Wakefield’s web-site are listed as sold out, but not my PET book. Interestingly, the next book produced by him, in a similar vein, An Alphabet of Endangered Mammals (2010), was editioned to 35 instead of the Extinction book at 55 copies. I would guess, and hope, that private collectors have purchased many of these 2 books, but I have not found a way to trace private collections. So there are multiple opportunities for this artist’s book to have varied after-lives. Also, this information insinuates that the audience for this book is primarily patrons of special collections, that hold artists’ books. I do know that the previous leader of special collections at Wesleyan, held as one of her foci books that address environmental issues.

I contacted the special collections librarians to find out if they kept records of how often a book was “called up” and what their policies were on removing items from the collection. Jenny Miglus (at Wesleyan University Special Collections) estimated that my Pet Book was probably called up 2 or 3times this past semester, as students research environmental issues (pers. commun. 11-20-23). I have learned from library blogs on-line that this process is called “weeding,” as in a garden and only by the most stoic librarians is it called “culling,” and the term “deaccessioning” doesn’t show up in the university library blogs I consulted. So, being concerned if my PET Book would be culled (seems the appropriate word for a book displaying extinct animals), I asked. The response is that they do not keep “granular” records on utilization for each book, and that it is extremely rare for special collections to cull a book. I was told that the bar is so high to get into the special collection that weeding doesn’t need to happen.

As an aside, I gifted a copy of my Beaver Bog Bestiary to Wesleyan University Special Collections in July, 2023. In that process, I signed a statement saying “Items not retained by the Wesleyan University Library shall be (option 1) disposed by the Wesleyan University Library in any appropriate way.” Which brings both my book and PET book to it’s after life in the library, and entanglement with whatever may happen to, or at, the library; and more broadly, what happens to human culture and society.

I recall appreciating a comment early in the course by Prof. Richards, that bookworms are vegetarian, and so parchment is less likely to be eaten away in that manner. Indeed, I have learned that larvae of beetles that can infest books do prefer cellulose (see https://artifactservices.com/emergency-care-insect-infestation-books/

, accessed 11-22-23). Imagining the conditions that could lead to bookworms in a library would have to do with loss of power to keep the “climate controls” of the library repositories functioning. I will leave it to apocalyptic science fiction writers to fill in those eventualities. In a more immediate set of circumstances, I can imagine fire, extended loss of power, collapse of building due to that rare (but no unheard of) New England earthquake (may it not be bombing of war), dowsing with water by a sprinkler system gone awry, or even a collaborative art project to reduce the size of the collection. I am guiding my choices here, based on a photobook collection by Rosamond Purcell. When Prof. Richards invoked bookworms, I came home and pulled out my copy of her book, Bookworm (2006). While I hope that none of these kinds of disintegration happen to D.R. Wakefield’s book of art honoring extinct animals, Rosamond’s imagery gives me more of a sense of how books can come apart at more-than-the-seams.

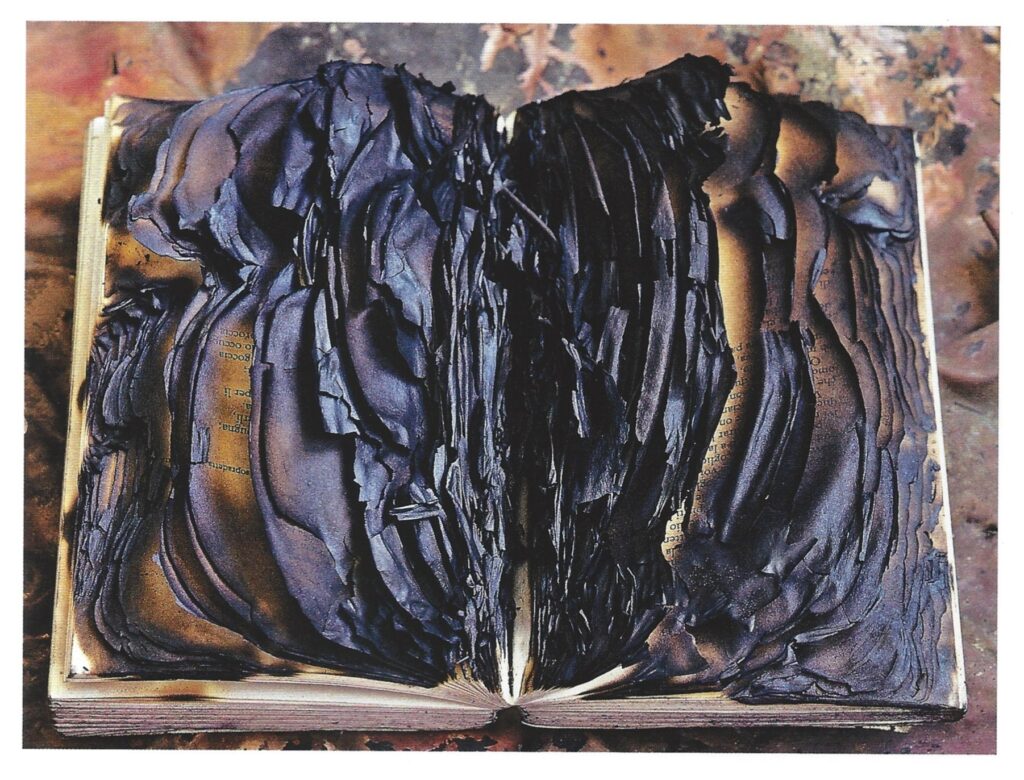

May fire not consume the ABCs of extinct animals, but if it did, would it look something like this Burned Copy of Dante’s Inferno (Rosamond, 2006, p.87):

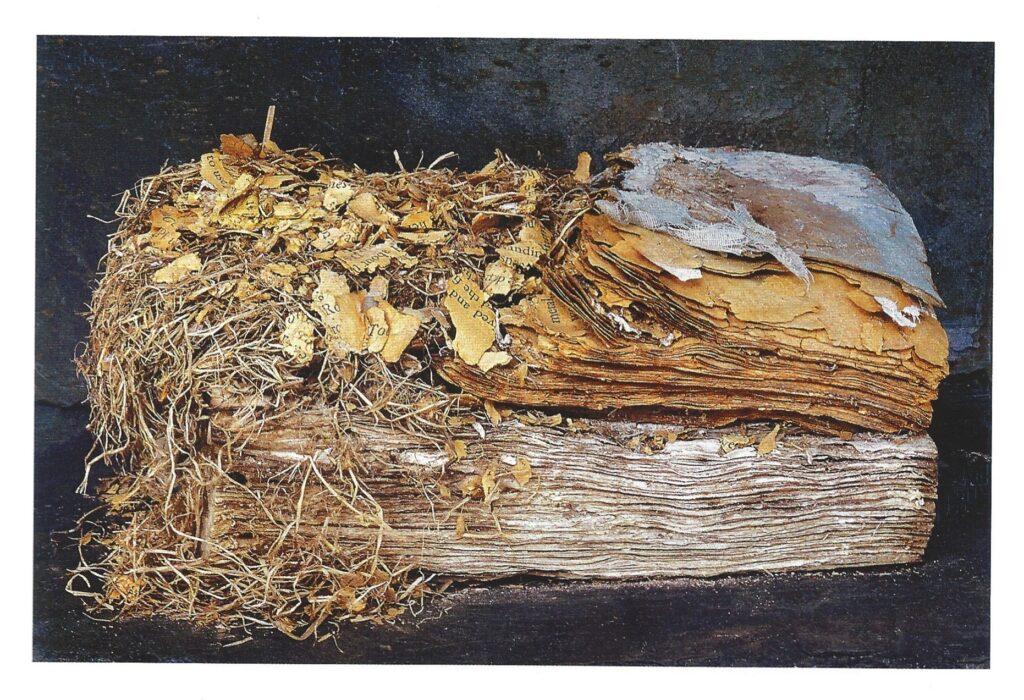

May mice, nor rats, find their way into the library stacks, but if they do, the colorful pages of Wakefield’s extinct animal prints could be made into a nest. Apparently rodents don’t actually like to eat paper, but use it for nesting and to sharpen their teeth (“Book Care: An Introduction,” http://rarelibraries.com/book-care/ , accessed 11-21-23) and Rosamond provides Book/Nest (p.39) to make this potential tragedy realistic:

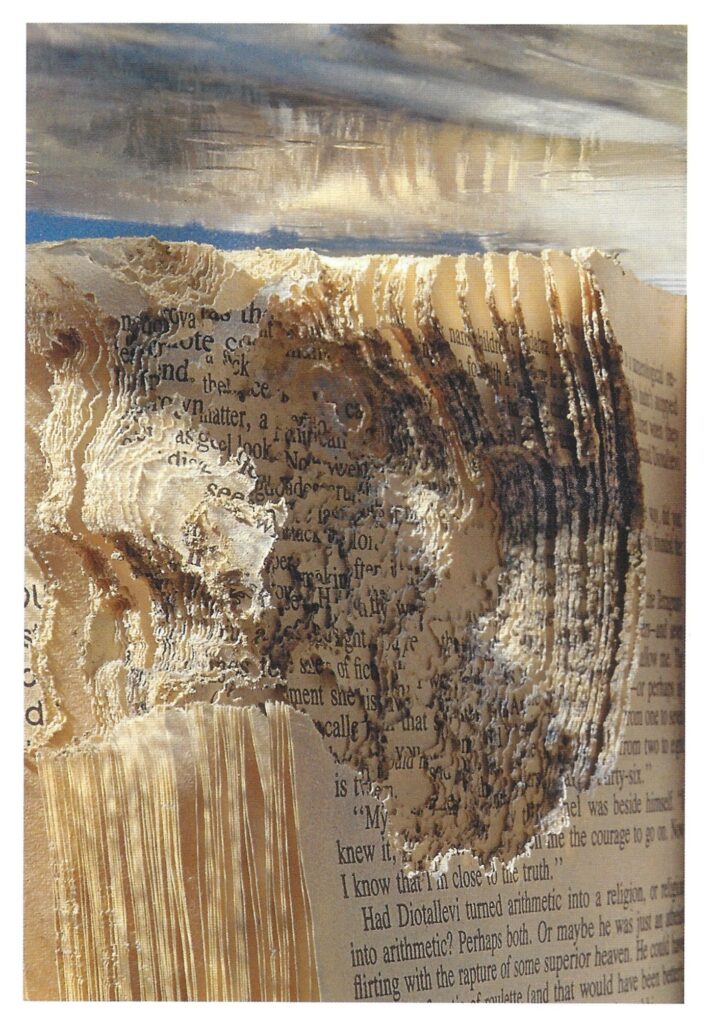

Termites have eaten through a book on Foucault’s Pendulum (p. 89) found in Bali:

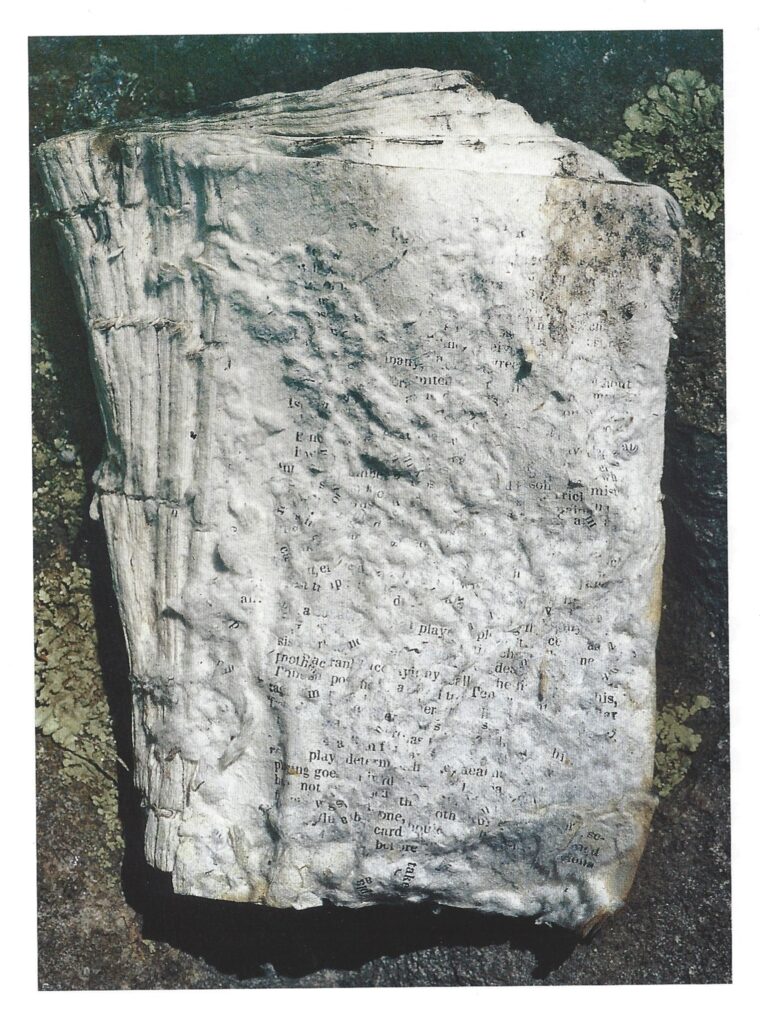

It seems that water has expanded and drifted apart the fragments that were previously pressed pages of paper in Play Goes Not Card Take (p.68). Rosamond’s title is a found poem from the discernable words on a page of what used to be a book. I imagine that Wakefield’s commentaries on the extinction of the animals would harbor many a stunning found poem after the text was soaked in a flood (perhaps from an errant sprinkler system, or a catastrophic flood of the CT River in Middletown).

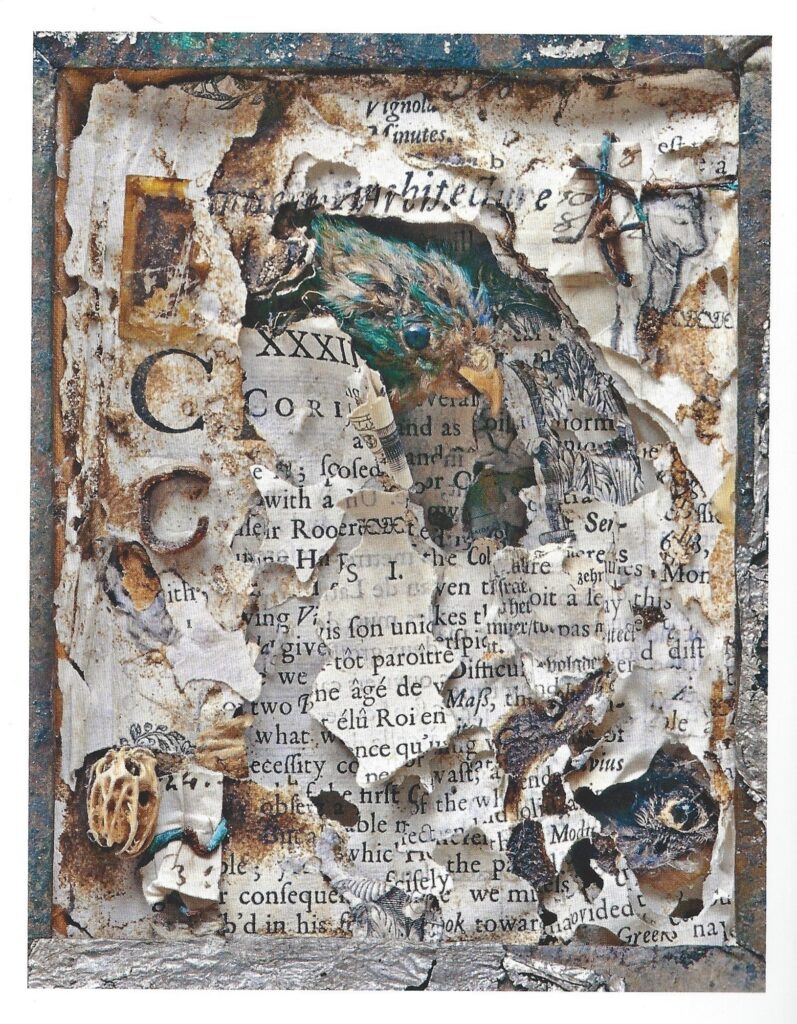

A found poem out of book tragedy, invites thoughts of purposeful creative collaboration in an effort to reduce the special collection size. Wakefield’s book would provide textures, colors, and surprising synchronicities of words in an after-life of extinction, even of his book arts. The collaged piece,by Rosamond, of deteriorated books and other found objects in a natural history collection invites ideas of collaboration between defunct linbraries and museums (Parrot Emerging from Language, p.82):

In our present reality, my PET Book is likely to hold up well to students and researchers turning its 100% cotton pages, and the bit of leather on the spine, embossed in gold, is in a climate controlled environment so it is not going to dry out soon and display red rot. The digital photographs of the book, taken by me and certainly at other libraries by other patrons, will ensure some form of digital life – as long as there are not magnetic events or solar flares that wipe out all these electronic missives. May the tactility of books endure beyond our digitization path, yet, all is ephemeral. So I am enjoying what is in this moment, appreciating different textures, colors, (I don’t have good smelling sense), and visual arrangements. I now have a better appreciation of how etchings can be layered to create images with depth, and the role of etching to expand the type faces that may be limited in a letterpress studio. I have signed up for a zoom conversation at the Center for Book Arts, that was supposed to occur before the due date of this blog post. It has been postponed, still, the synchronicity of the offering for the development of my ideas for book arts is encouraging to me, and I look forward to it: “Books As A Prompt for Discourse.” The combination of creative expression in book arts, natural science, and making an offering to encourage an ecological consciousness shift continues to hold my attention.