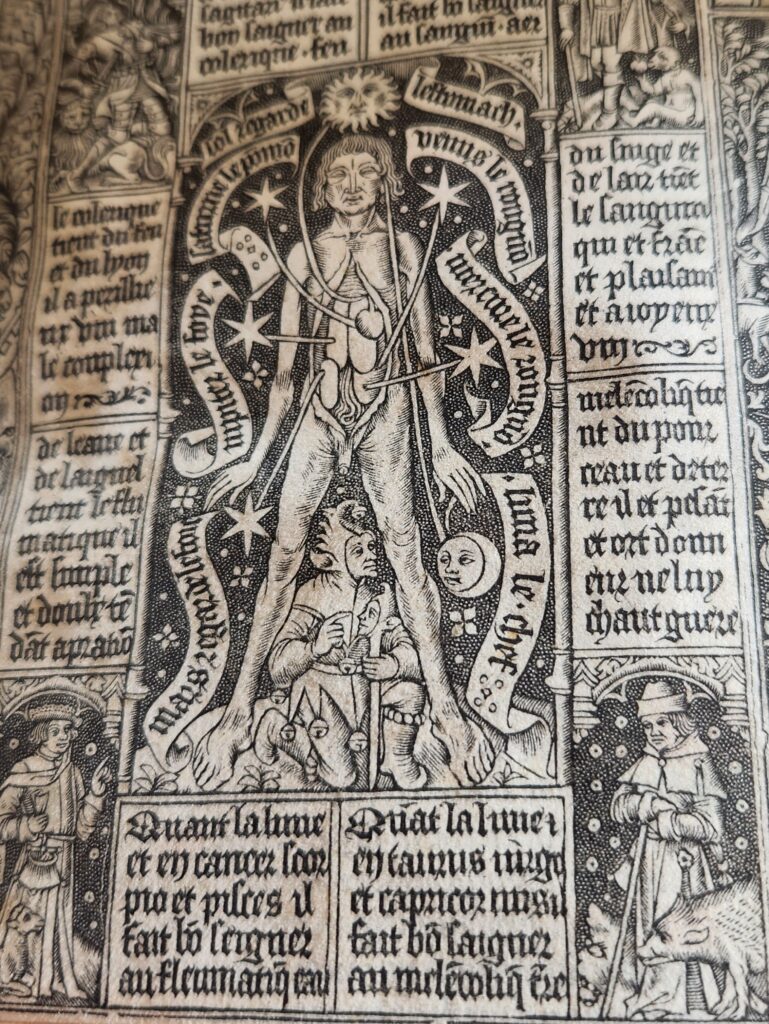

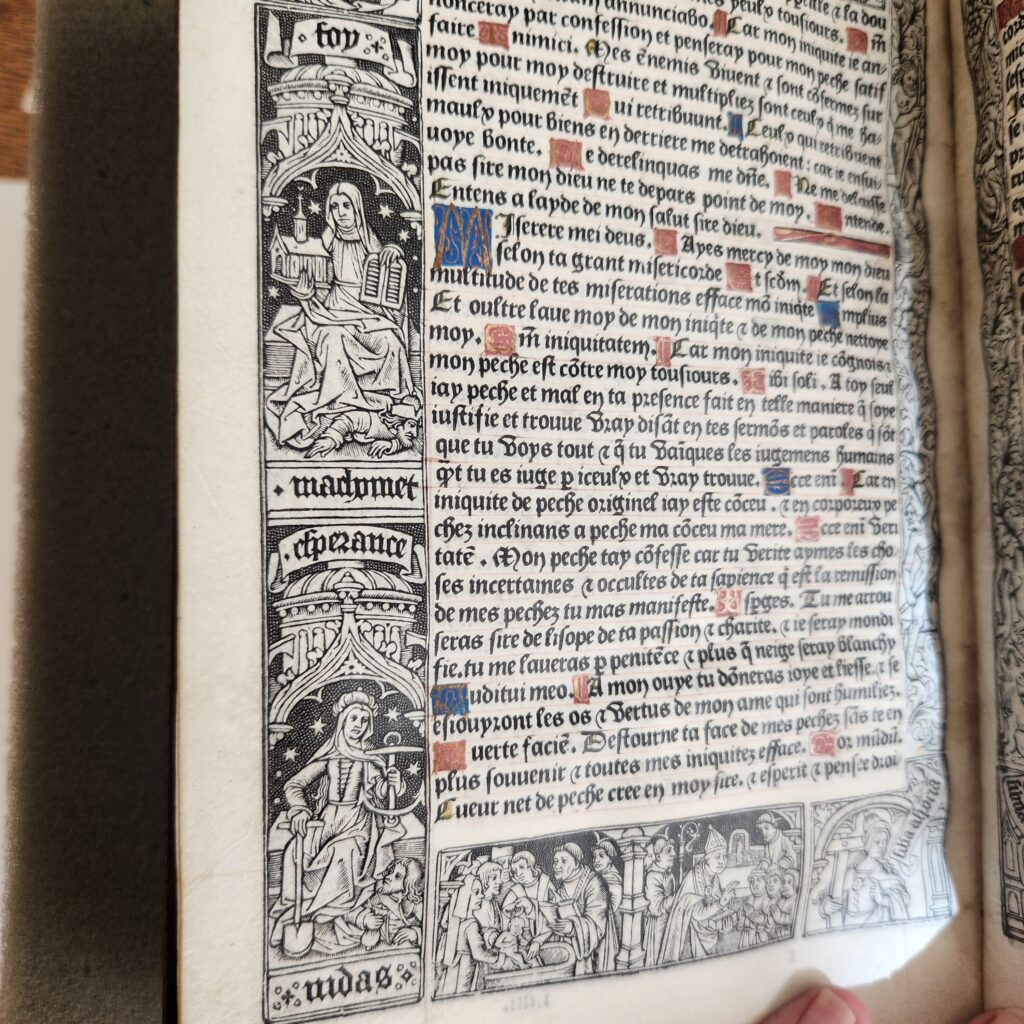

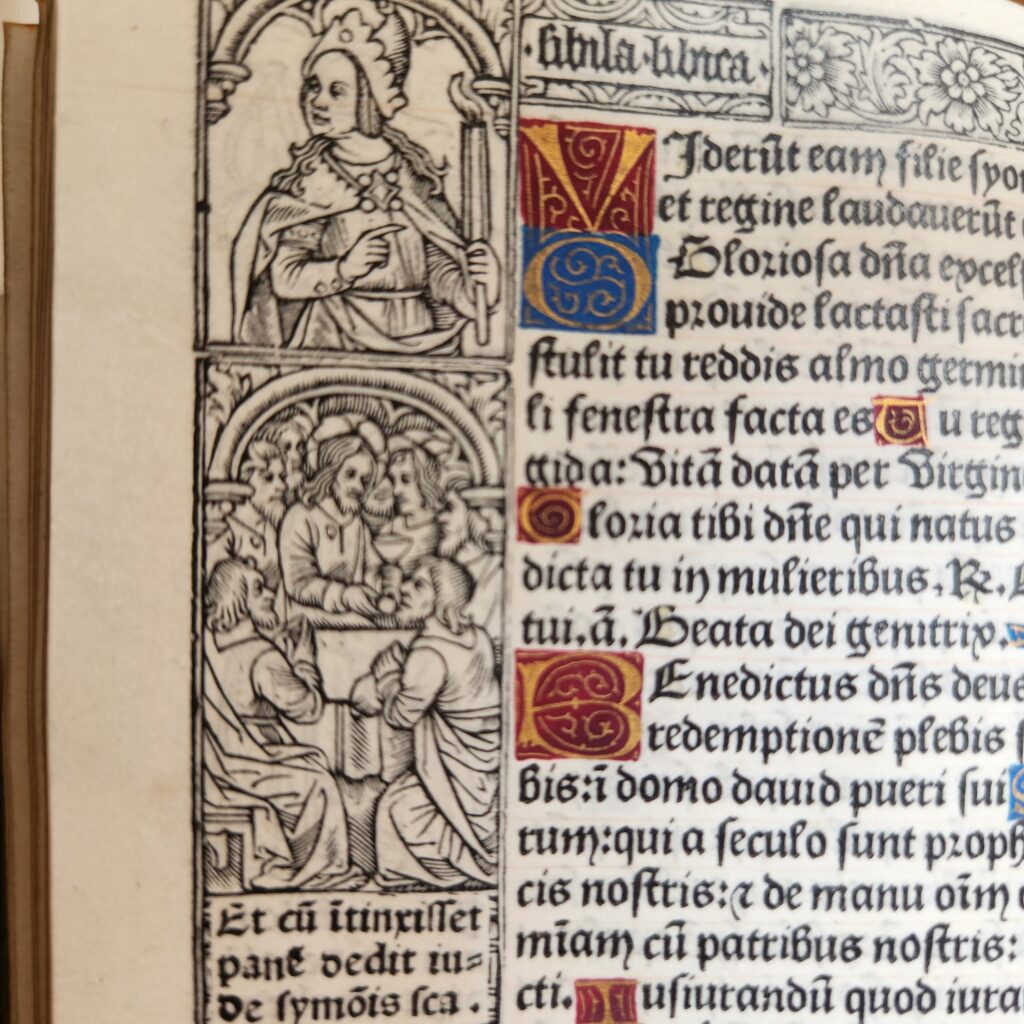

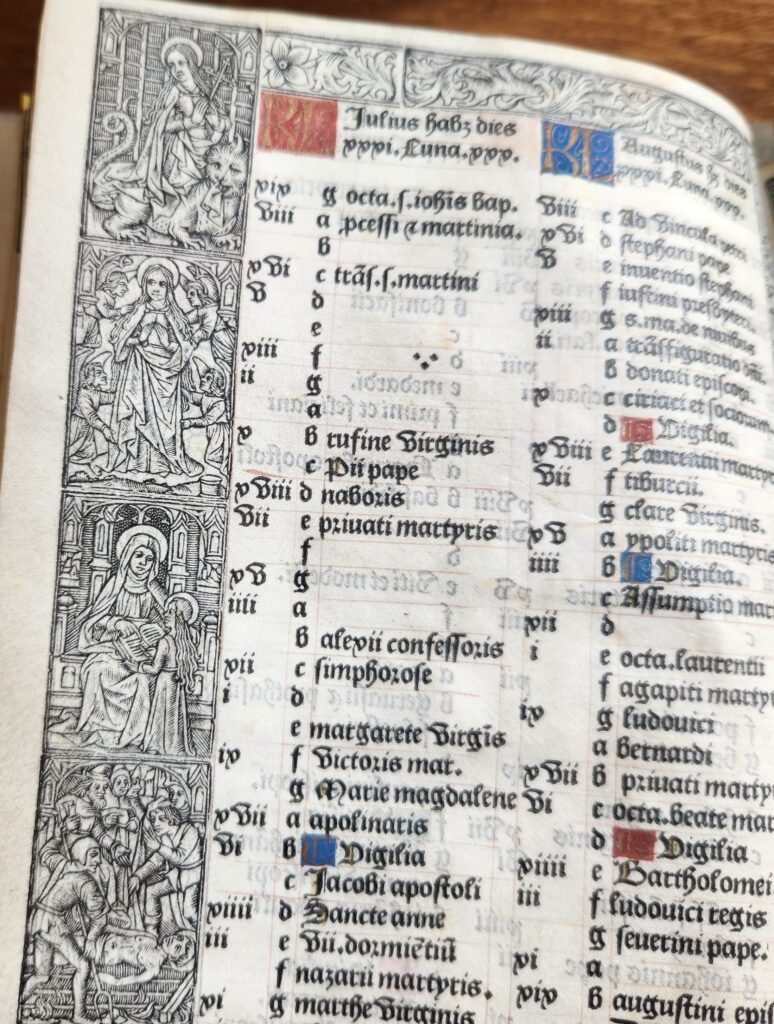

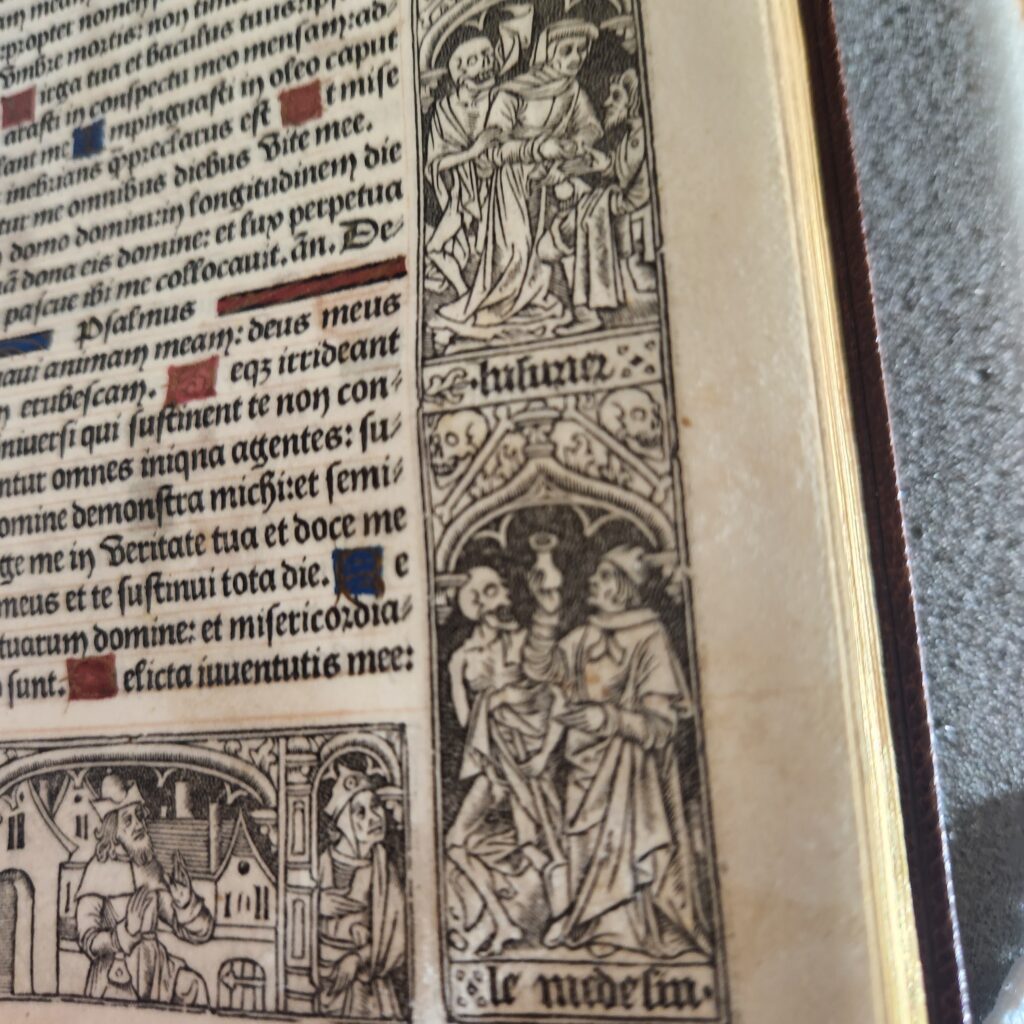

The vast majority of images in my Book of Hours are marginal illustrations. They surround the text block on all four sides in their own panels. Although there are also a number of framed miniatures, illuminations that take up the entirety of the text block, most of the pages look like this:

I believe that all of the images on these pages were created through a woodblock printing process, as they are made up of irregular lines that end in a point. There is nothing fluid or uniform about these illustrations; an etched process would have produced a very different style than what we are seeing on the page. Therefore, these images and their accompanying text are likely the result of relief printing.

Because I do not read French or Latin, I had to infer most of what was going on in the illustrations. These woodcuts, I think, are an example of “narrative” depiction, where the story of the image roughly corresponds to the story of the text. However, while these images are certainly interrelated, they each tell their own story as well. Many of the early pages feature calendars with saints’ days, which are surrounded by images of the saints themselves getting martyred or performing miracles.

Loosely defined, this is a continuous narrative, as the images are linked together by a common theme, but each image tells its own story as well. After this section, most of the marginal illustrations in the first half of the book are scenes from the life of Jesus. However, after that, I began to lose the narrative thread. The second half of the book seemed to depict miscellaneous Biblical stories of disasters and human suffering, as well as a very intriguing section in which various figures appear to dance with Death in each panel. It was at this point that I had to look up the structure of a Book of Hours in order to make any sense of it. According to Harvard Library, the sections following the life of Jesus include prayers and parables of penitents, sinners and martyrs. The final “Office of the Dead” section sometimes include a “Dance with Death” a sequence in which people from various walks of life are accompanied by a skeleton to remind the reader that death comes for everyone. Thus, the images are narrative but also emblematic.

What intrigued me most were the images in the pages following the “Dance with Death.” These woodland scenes depict human figures hunting, gathering fruit and merrymaking amid nature. They are interspersed with panels of supernatural creatures, beasts I might have expected to come from “pagan” traditions such as Hellenism. It was strange to find these “heathen” creatures surrounding the Christian text. Since these images appear primarily in the final section of the book, I thought they might be representative of Paradise. There are also a few “real” animals about, such as this lion:

I don’t think the person who created this image had ever seen a lion before. It reminds me of our study of medieval bestiaries and how the depictions of nonnative animals often took on a life of their own. As Michel Foucault theorized, the representation of an object is not the object itself, but it has its own meaning apart from the object which affects our perception of it. However, how does this apply when the object in question does not exist at all, except for in the imagination? As we said in class, our imaginations are limited to what we have experienced in this world. Therefore, how do we interpret this figure below:

This creature seems to be a man from the waist up, a lion from the waist down, and, bizarrely, the enlarged head of an exotic bird from the rear. This raises another question: can even an imaginary creature be accurately represented if the artist who created it does not understand the concepts he used to construct it? Or is an act of the imagination exempt from the standards we hold to representations of reality, even though our imaginations are shaped by reality? Furthermore, this being appears to be a composite of two composites: a chimera and a centaur. I don’t know if the artist was consciously trying to emulate these mythological concepts, but it seems likely he would have been aware of them. In fact, the entire book is full of seemingly pagan imagery – astrological symbols, anthropomorphized animals, the metamorphosis of humans & nature. I am curious to understand how an idolatrous image used to represent the Word of God affects the rest of the text. Is this sacred work imperfect if it acknowledges traditions that the text itself proclaims false? This is similar to Mazzaferro’s case of exemplarity vs. exceptionality: the images on the page contradict the teachings of the words. Viewers are inundated with visual allusions to other divinities while the text forbids them from practicing anything but strict monotheism. There is a struggle between the visual narrative in the panels and the verbal narrative on the page, a contradiction that is present even when the reader cannot understand the words.