Blog Post #3 by Becka

Every page in Euclid’s Geometry has images on it. There are two main categories of pictures in this book – pictures that are useful for explaining geometry and pictures that are not.

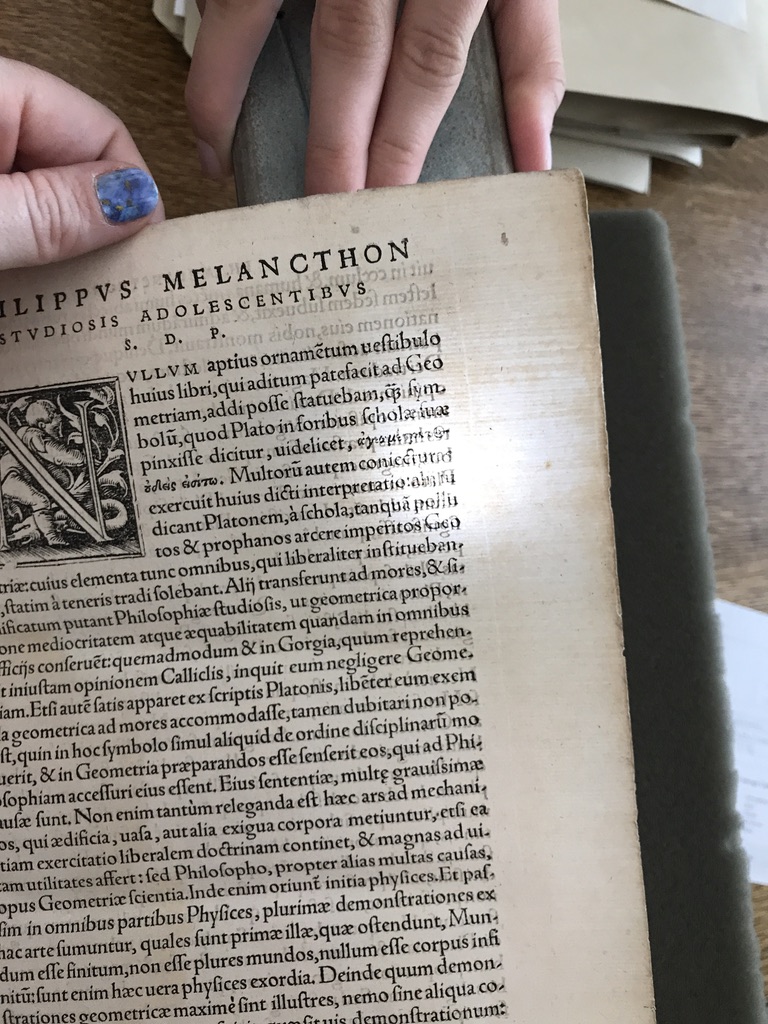

With the help of another person in the room, I photographed shining a light through the page to see if I could learn more about the printing process. I have terrible vision and was unable to tell if the ink was on top of the paper or flush with it. I was able to tell that the text is in the book via a printing press as you can see and feel the indentations the letters made. I tried to get a photograph to show this, but all of them came out terrible.

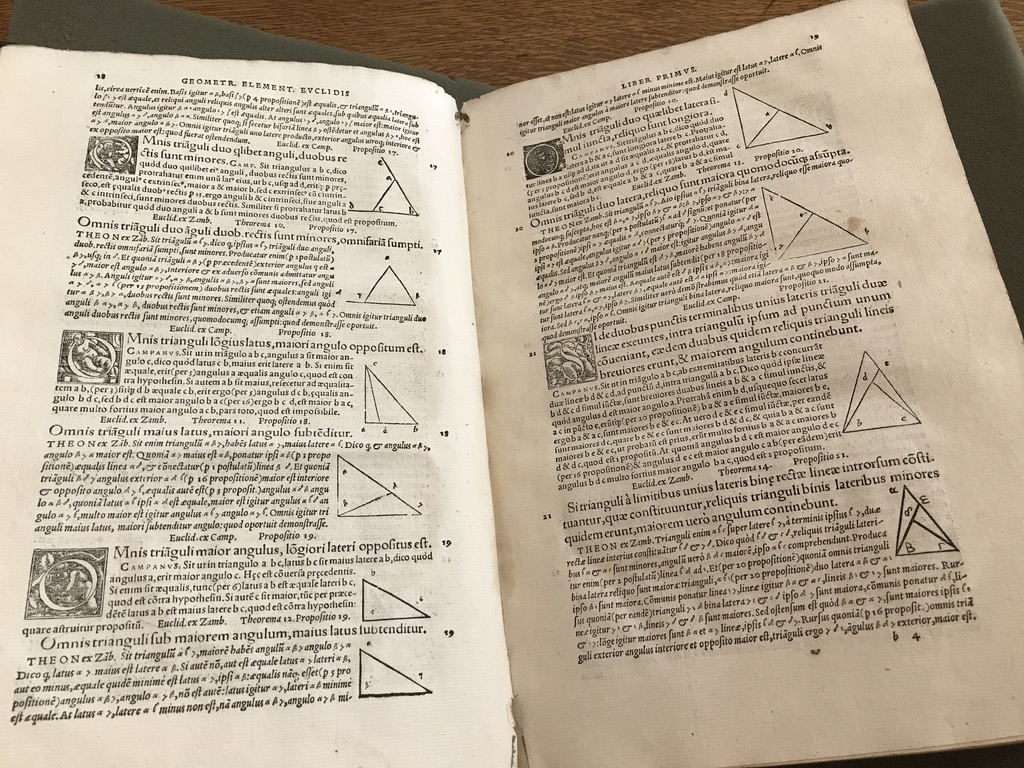

Printmaking is my second favorite type of art to do, after fiber arts. I’ve done linoleum block printing, silkscreening, monotype, lithography, and etching, and plan to take woodblock printing with Keiji in the spring. Zooming in on all of the images throughout the text, I am convinced that they are woodblock prints as the lines aren’t as fine as one can get with etching, and all of the lines are the same darkness Also, this book predates the ability to do shading and tonal techniques in etching via aquatint.

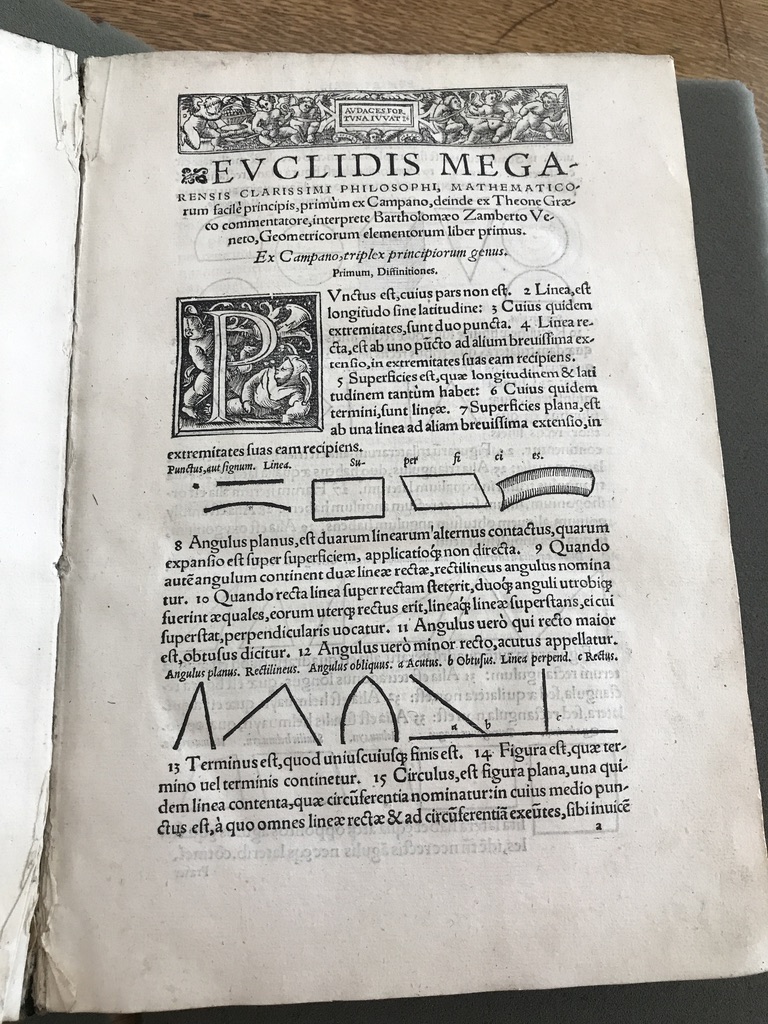

The non-geometry images in this book remediate medieval texts. As seen on page 1, there is a framed miniature across the top of the page and a historiated initial. Many of the pages have the initials, as seen in the pages below.

I cannot read Latin, but I do know math. These non-geometry images, as I’ve stated before, have nothing to do with geometry. The historiated initials remediate the ones we saw in older tomes, such as Bibles. But, the writing in the first line with the historiated initials is larger than the following lines. My best guess is that these images are there to signify how important the paragraphs they start are.

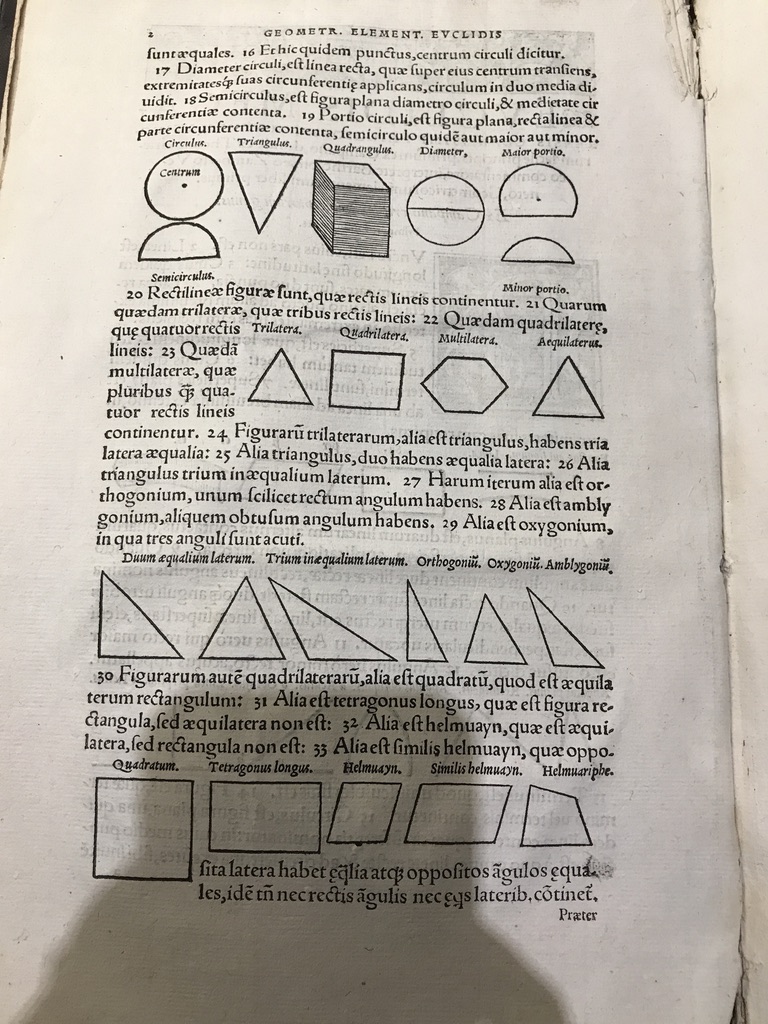

My favorite images in this text, even though they are so plain, are the geometry pictures. Sometimes they are imbeded within the text, sometimes there is space between paragraphs for them. They are labeled. Sometimes the words appear above the image, sometimes it is letters within the shape, which must represent angles. These images aren’t here for decoration – they are here for learning purposes only. Even though I don’t speak Latin, based on how clear the images and labels are, I can deduce that “ciculus” means circle and that “centrum” is the center of a circle.

Based on the publication date of this volume, 1546, one might think that it is a remediation of the medieval bestiaries. As bestiaries were the oldest texts we looked at that had images that were there for the purpose of learning new information. But, Euclid came up with geometry around 300 B.C.E. And that is before bestiaries existed. Based on its age, Euclid’s Geometry was originally written on papyrus in Alexandria, and there must have been geometry drawings in it. And then, like most surviving ancient Greek work, it was translated into Arabic, and then we have it in Latin, like this copy here. So, since Euclid came first, is the labeling and describing nature of the medieval bestiary actually a remediation of Euclid? Or is this book just a remeidation of itself?