Gaynell’s Blog Post #3

Despite the title indicating that my Pet Book is an alphabet book, it is not highlighting the alphabet in an instructive way, so I would hesitate to classify it as an abcedaria[1]. The connection to ABCs is structural as the animals are included based on the first letters of their common name (with the exception of the Xenarthra which relies on a “group” name[2], instead of common name, to provide the letter X). There is no separate highlighting of the first initial, with the one exception of Oriente Cave Rat (described in the previous post). The intent of awe and wonder is present – as these animals are not to be seen unless as taxidermy in a museum or photography or painting from the colonial era. They are exotic to us now. The larger folio size of the book also carries a reminiscence of children’s books, although this one is in portrait orientation rather than landscape. A stronger connection to the tradition of abcedaria is in the moral messages of the text accompanying each extinct animal’s image.

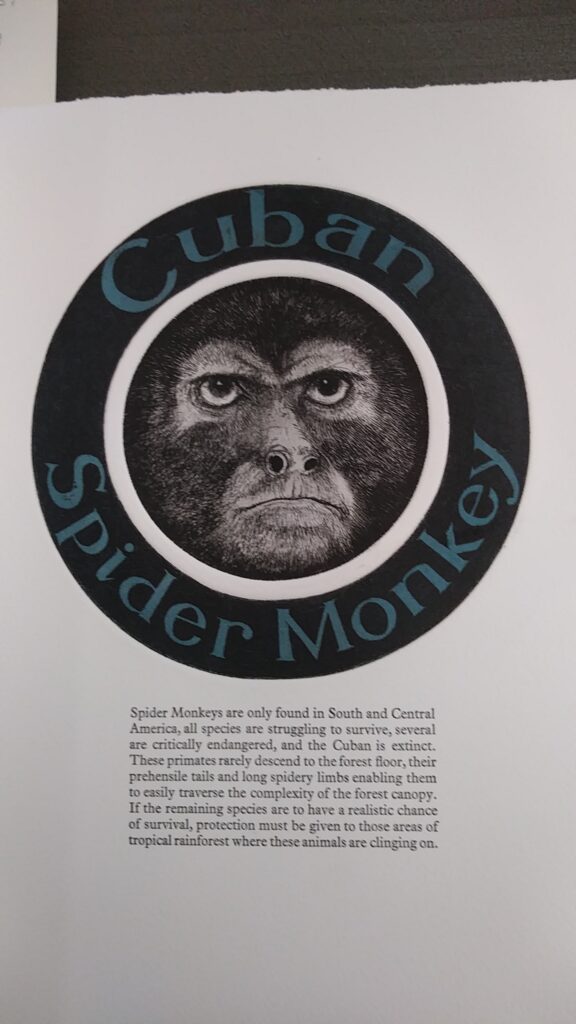

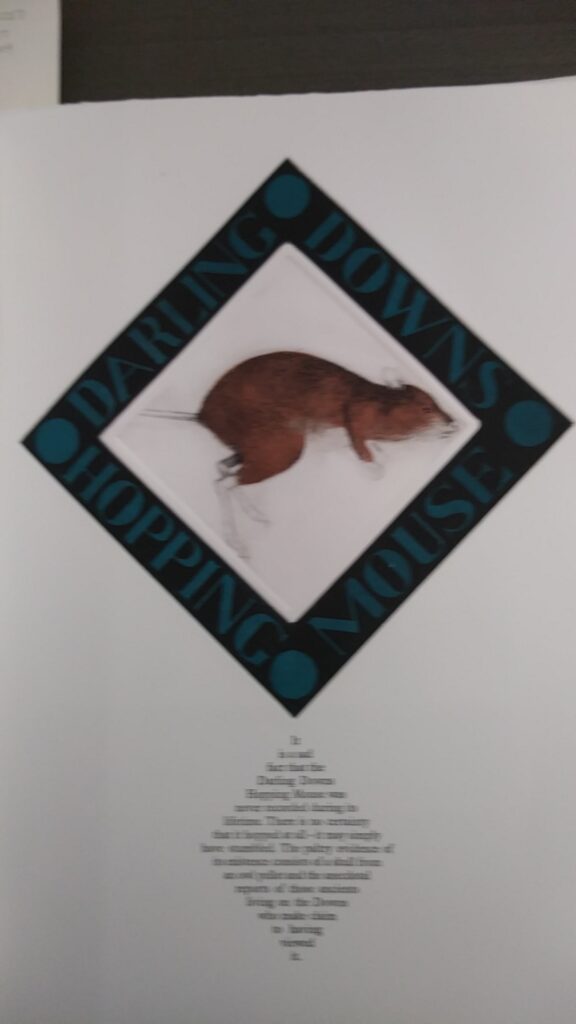

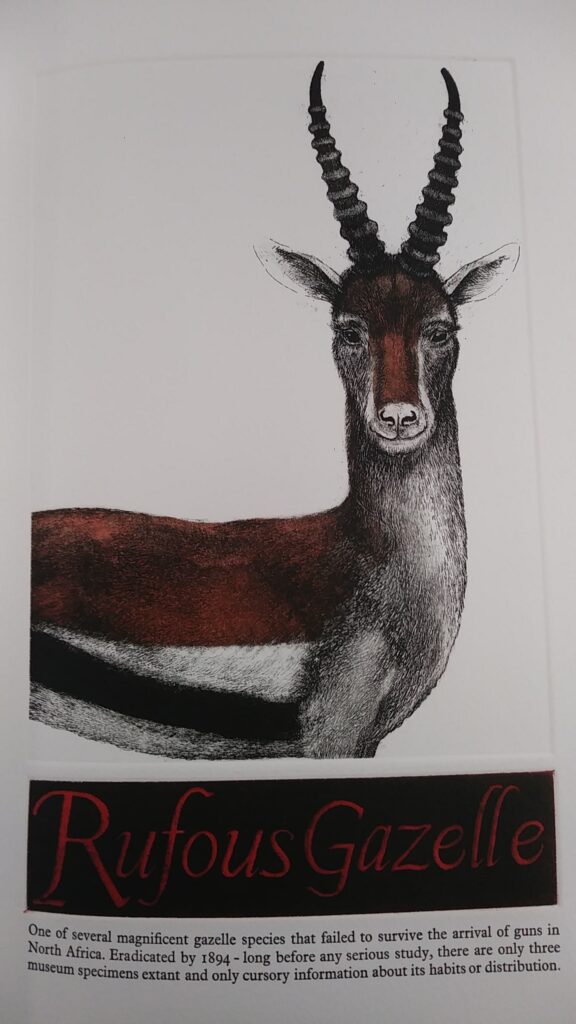

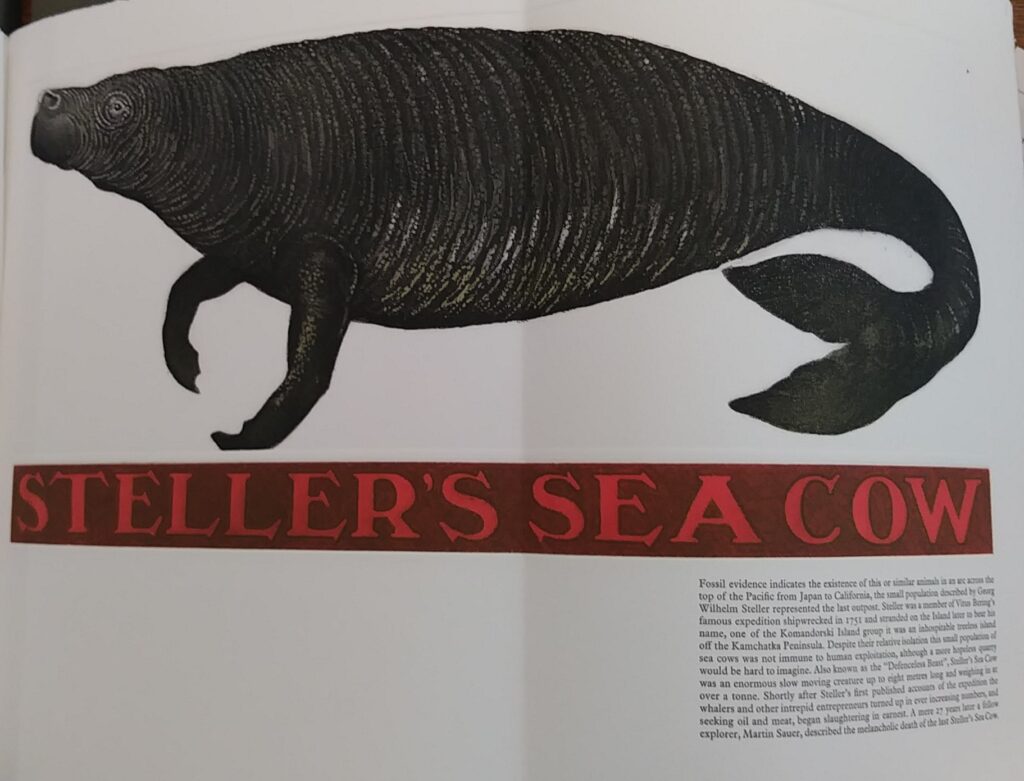

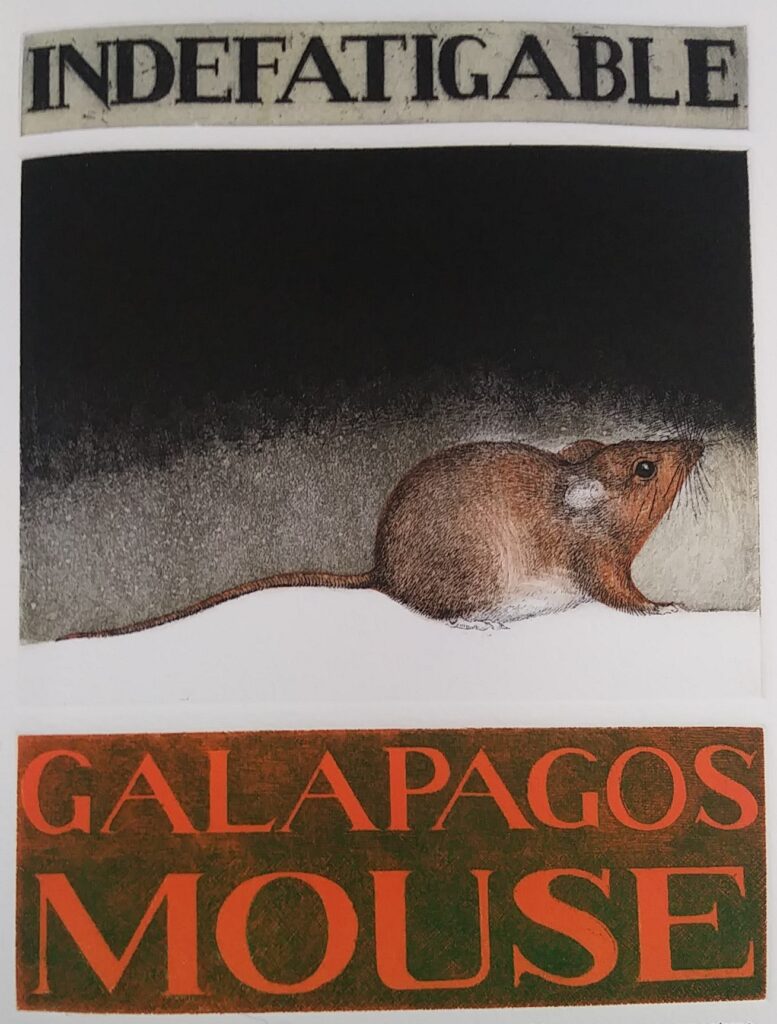

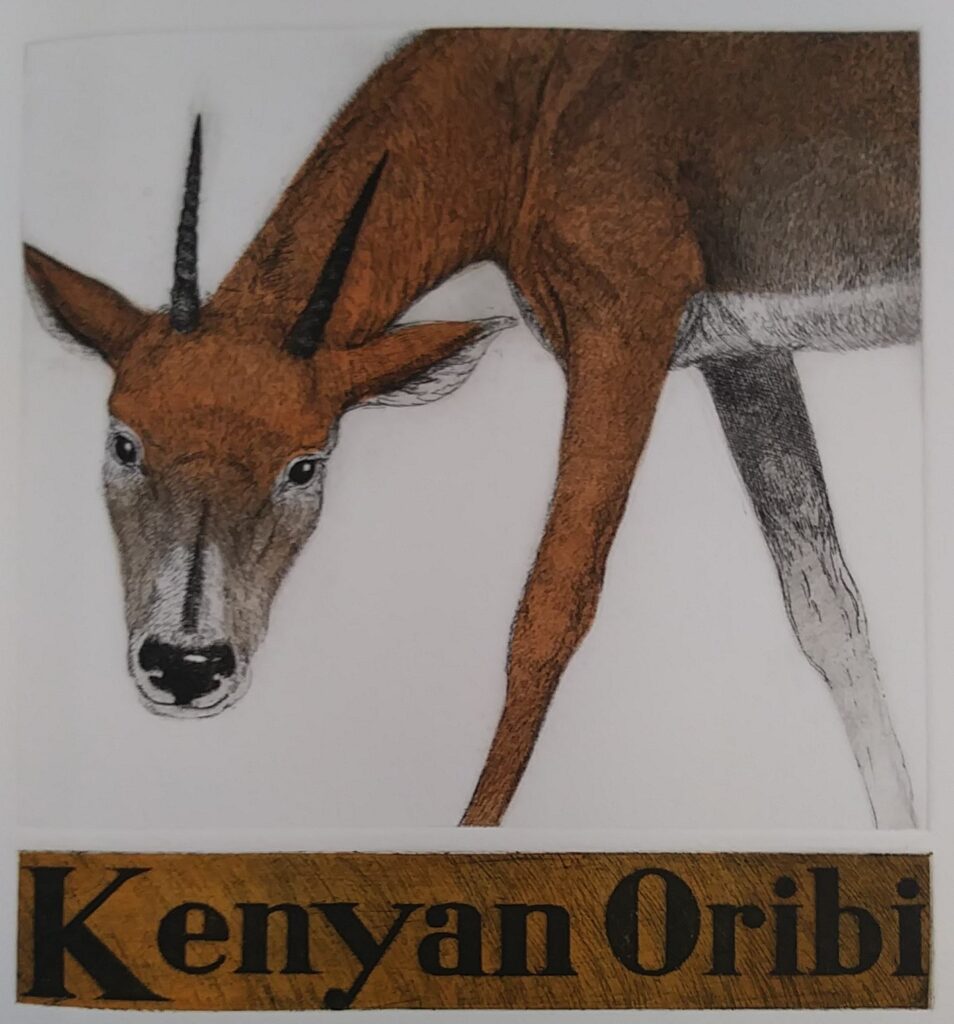

The name plates of the animals, as described in the previous post, are done in varied fonts. The color of the name plates and the colors of the images are aligned in some way on 13 of the pages, by repeating some aspect of the color (or just black) used in the animal image. Black letters are used for 8 of the animal names, and a black background (with colored or grayed letters) is used on 8 of the animal name plates. The ten others are color intensity variations, or color with an overlay of black texture. Flow is supported between some pages by color in the name plates, such as in Cuban Spider Monkey, to next page’s Darling Downs Hopping Mouse, both with blue letters on a black background and creating a frame around the animal image. The Rufous Gazelle and the Stellar’s Sea Cow both share in red letters (a possible awareness of rubrics). The West Indian Monk Seal and the Puerto Rican Sloth (part of the Xenarthan name) share in shades of red letters. Use of black, particularly from an English artist/author, likely is symbolic of “black death” and so these extinctions. The use of red could be inferred to note a blood letting redness, or even the red-letter-day of these animals passing out of Earth’s ecology.

Note the red letters in the name plates from “R” for Rufous Gazelle to the next page’s “S” for Steller’s Sea Cow. The Rufous Gazelle is a fine example of the print-maker using both black and red-brown inks on two separate plates (likely) in a duotone process, as well as utilizing the white of the page to make shades of gray from the black inked texture marks.

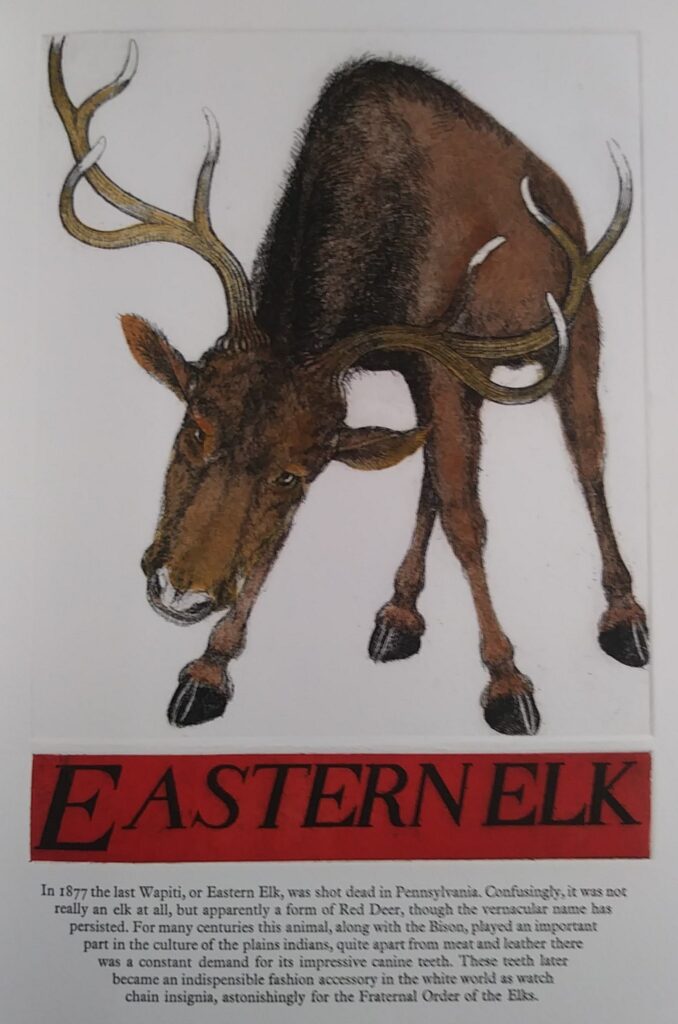

The moral message in the book is clear. The author’s text blocks make it clear that European colonialism; through the introduction of European Rats, habitat destruction, and guns; is the intervention that lead to the demise of these animals. Ten of the animal extinctions are attributed to guns, and their introduction by Europeans. Government bounty programs, trophy hunting, and harvesting for food contributed to the extinctions by guns according to this author. Three extinctions are related to European rats imported inadvertently onboard ships (Indefatigable, named after one of those British warships; the New Zealand Bat, and the Oriente Cave Rat). The Darling Downs Mouse was likely done-in by imported cats. The Hispaniolan Hutia was done in by Mongoose, imported to eat snakes. Whalers are also held responsible in the text for the Stellar’s Sea Cow’s demise. Habitat destruction, by human economic activity, is named in the extirpation of the Cuban Spider Monkey, the Lesser Madagascan Flying Fox, the Pig Footed Bandicoot, and the Yangtze River Dolphin. Not all the animal extinctions are so pointedly attributed to humanity, but rather humans are insinuated as the culprit (by eating the Madagascan Pygmy Hippo and Vietnamese Warty Pig and killed out of fear of the Utah Grizzly). It is this telling of the species demise in the text block below each animal image that creates what dynamic there is between letterpress-words and image. The name plates, being produced as etchings in the same manner as the image of the animal, are holding a stronger energy of connection of words with the images.

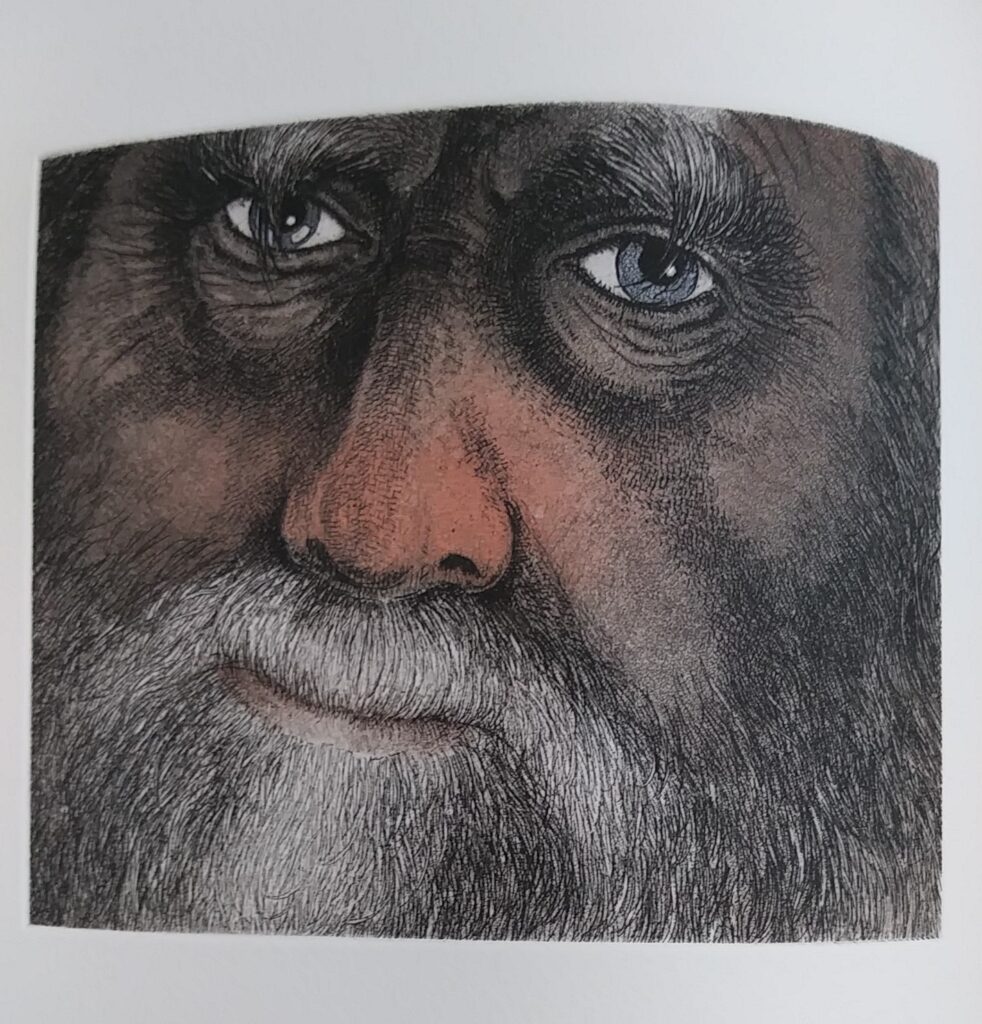

The printmaker and author of this Pet Book is D.R. Wakefield, and presumably it is he who is staring out at us from a curved top rectangle on the verso to the title page. That first and only human image, referencing the authorial image in book history, is the only image without a name-plate. Is it that hierarchical thinking precludes the need to name the human portrait? Or could it be that refusing to name the human animal is a way of allowing the authorial image to represent more of humanity than the individual, just as each of the alphabetized animal images represent a species gone extinct and not just an individual’s death. Frontal face views are presented for seven of the animal images, in addition to the author image. This eye level perspective “..allows viewers to feel more connected with them (the animals) – especially if the subject is making direct eye contact…It evokes a sense of familiarity and empathy, even with animals we would be frightened to find ourselves face to face with in real life.”[3]

The whole body (or almost all of the body, as in the Zebra Wolf, who is included in this count) is imaged for 13 of the animals. These whole body images are lateral views, except for the Eastern Elk which is a head on view. Three images are facial portraits (the Cuban Spider Monkey looking straight at us, and the side facial view of the Falkland Islands Dog and the Quagga). The other ten are upper third to two-thirds of the animal bodies and heads.

The etching process of animal images and name plates was described in previous blogging. Here I add the detail that both images and name plates (with more than just black and white) are likely done in a duotone process, meaning there is one plate for black ink, one for a colored ink, and white of the page are combined to give highlights and shades. As in serigraphy, the overlaying of colored ink with texture imprint of black ink enhances the felt range of shades. The 10 name plates mentioned above as not being variations on black and white of page, are variations on a single color’s saturation (color intensity is thinned, likely with a transparent medium) or black is added as a texture, creating a shade. The printing process of images and name plates potentially carries subtle meaning aligned with a book on extinctions: the etching plates “bite” the paper, the plates he makes are often “shaped” rather than metal forms as originally provided (human colonial tendency to shape habitat and ecological inhabitants, rather than appreciating what is present), the shades created by texture marks in black pull a shade down on these lives, and the thinning of colors with a transparent medium is an incremental move toward the whiteness of the page (and the whiteness of colonialism). Whether or not D.R. Wakefield carried his intentions this deeply into process is conjecture.

[1] “Also called abcedaria, abcee, abcie, or absey books, ABC books contain, in addition to the alphabet, depending on their historical function, a selection of illustrations, rhymes, a syllabarium, prayers, biblical texts, or stories. Originally alphabet books were developed to teach children spelling and reading, but soon they started to serve more purposes than the mere instruction of the order, sound, and shape of the letters. The genre evolved into an instrument of religious and moral instruction, and nowadays most ABC books mainly serve to amuse children with illustrations, stories, and rhymes when they already know the alphabet.” — Joosen, Vanessa. “ABC Books” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature. Vol. 1. Jack Zipes, editor-in-chief. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. And here remediated from web access, 11-4-23, of https://library.mcla.edu/childrenslit/alphabet.

[2] Xenarthra is a magnaorder of mammals according to Britannica (https://www.britannica.com/animal/xenarthran ).

[3] Eye level imagery is a perspective defined by https://www.nyfa.edu/student-resources/point-view-photography/ accessed 11-4-23