Specimen Botanicum is an informational, educational, scientific text with a distinctive layout that is still used today. The text is in Latin; I used two apps and my vague memory of high school for the translations.

mise-en-page

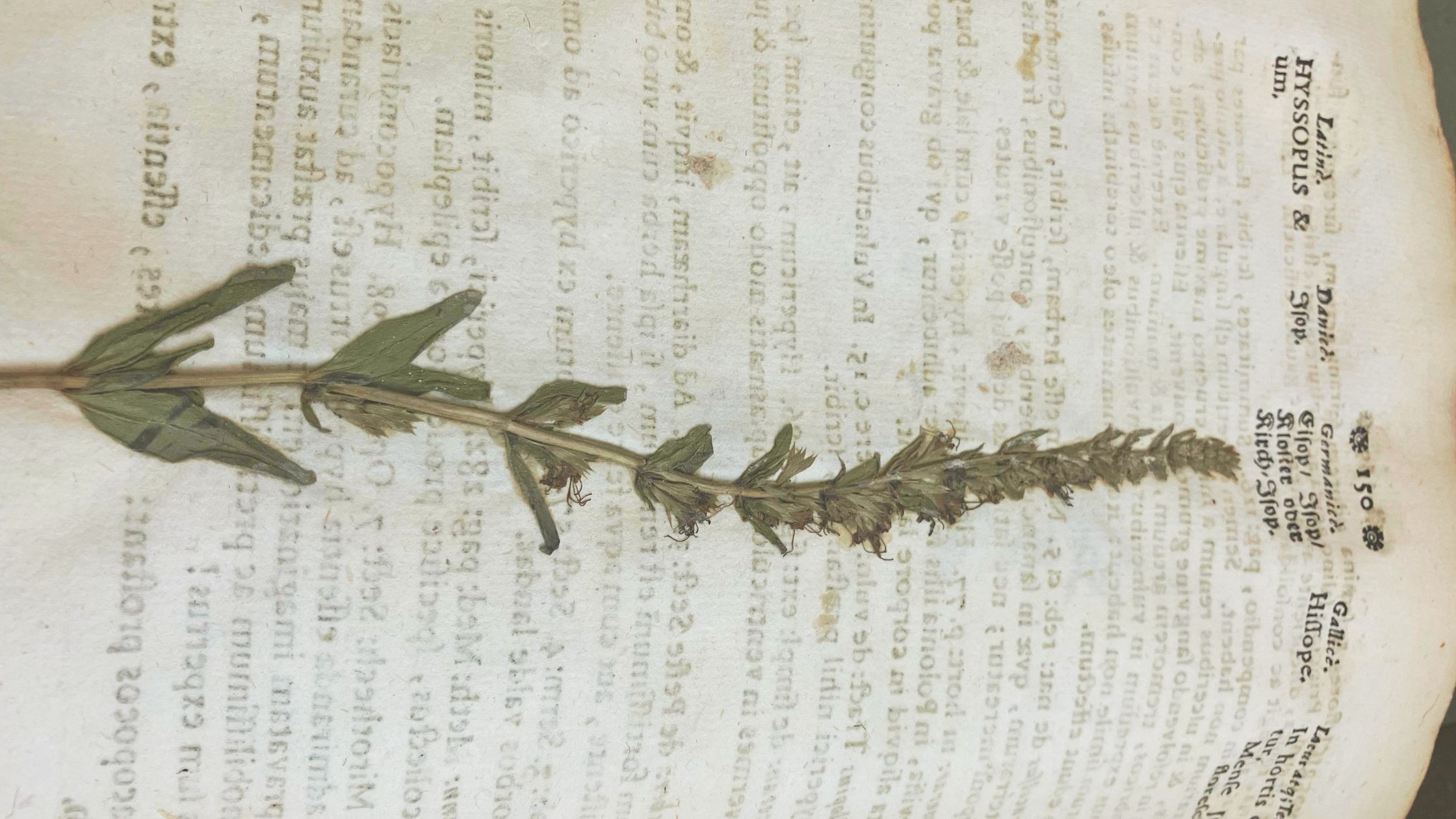

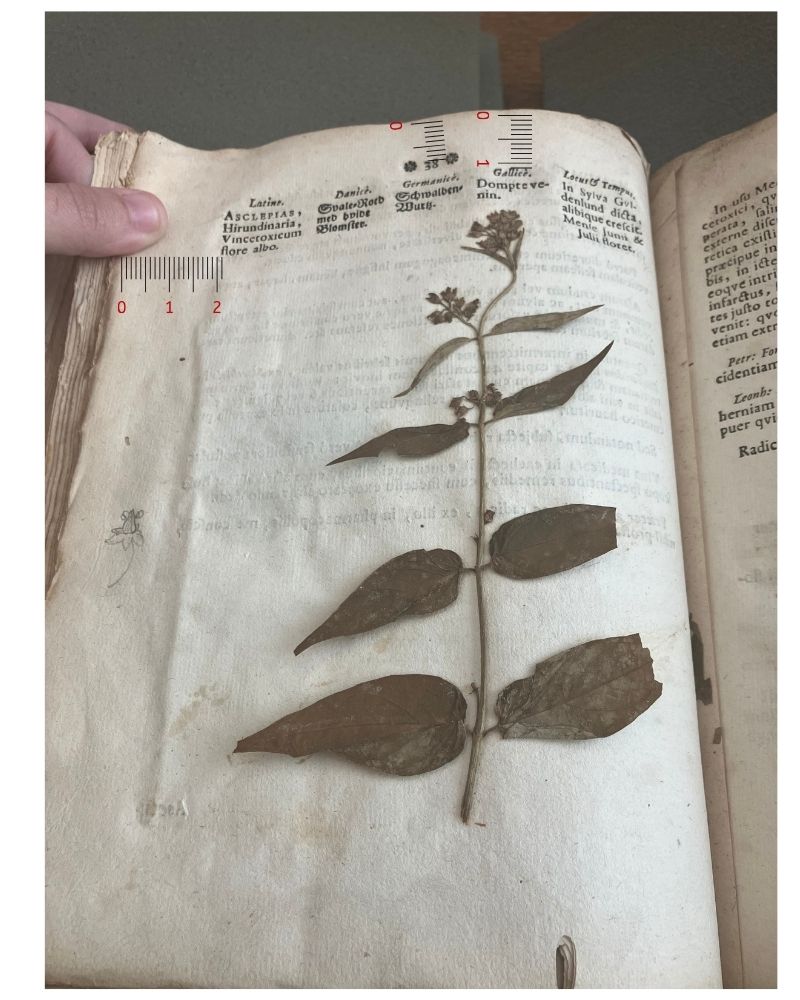

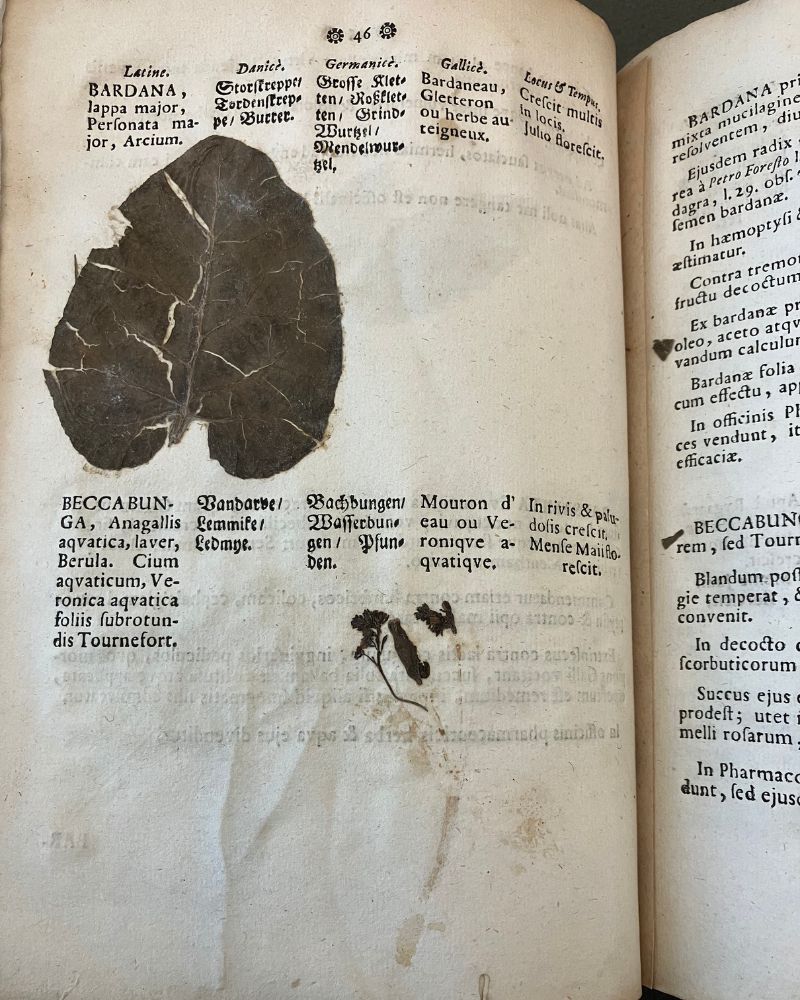

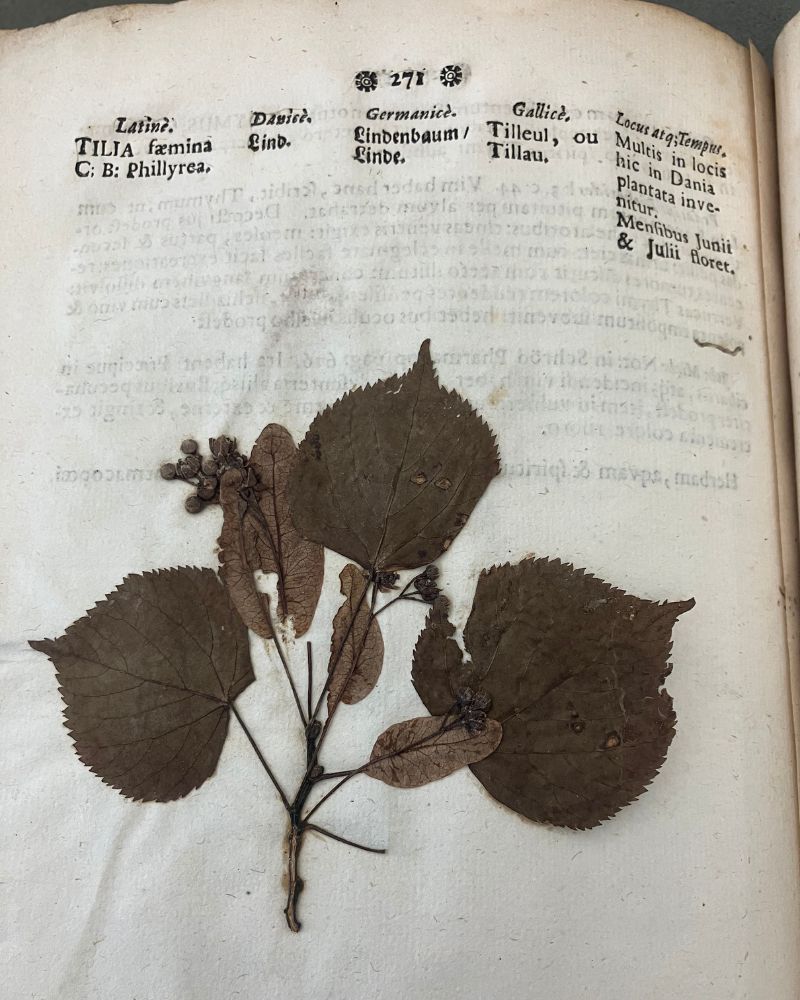

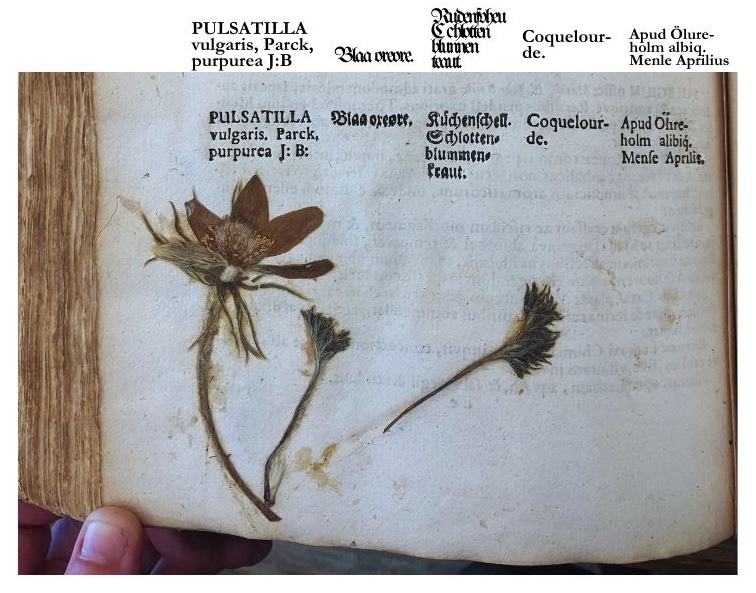

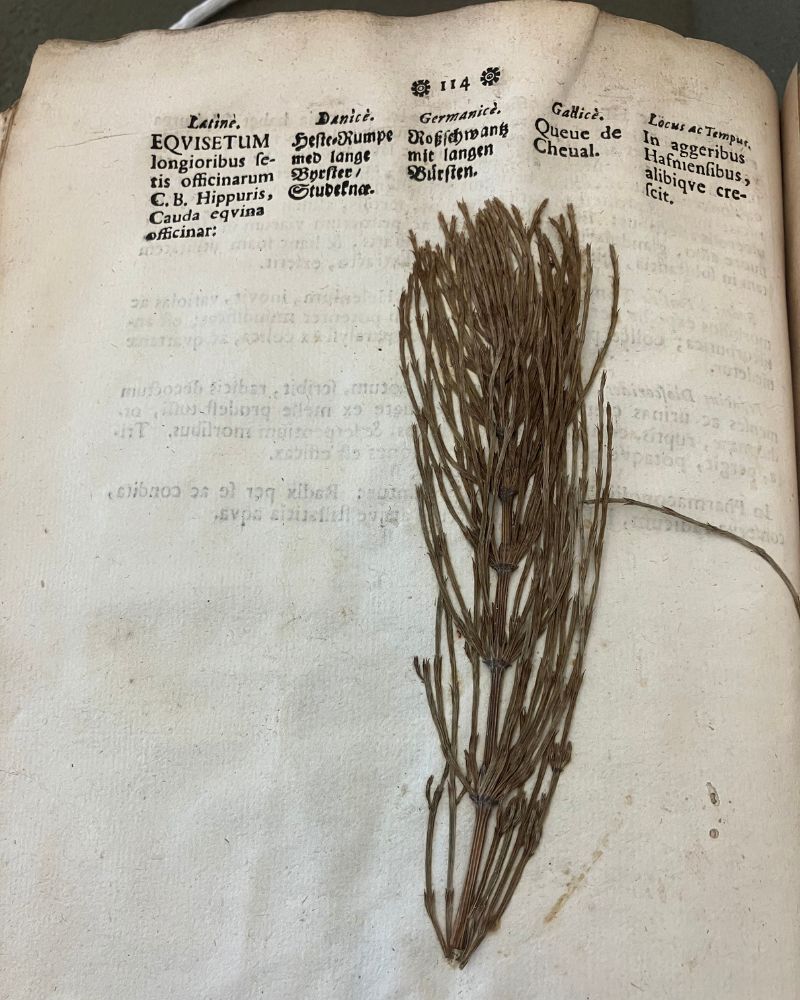

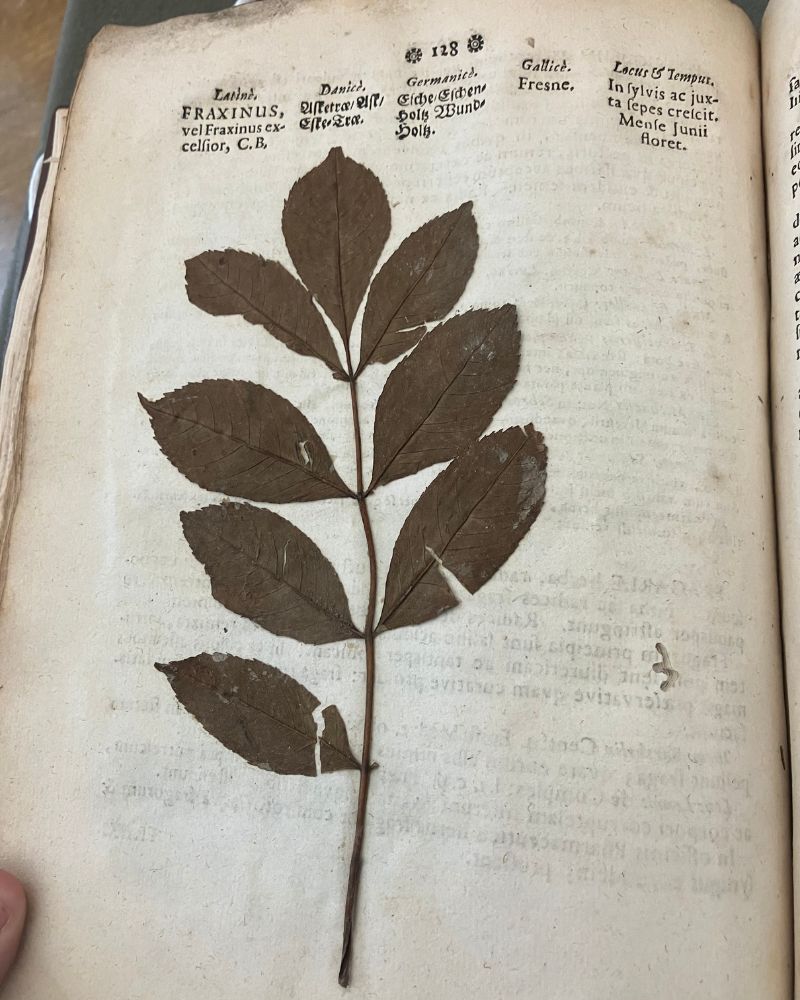

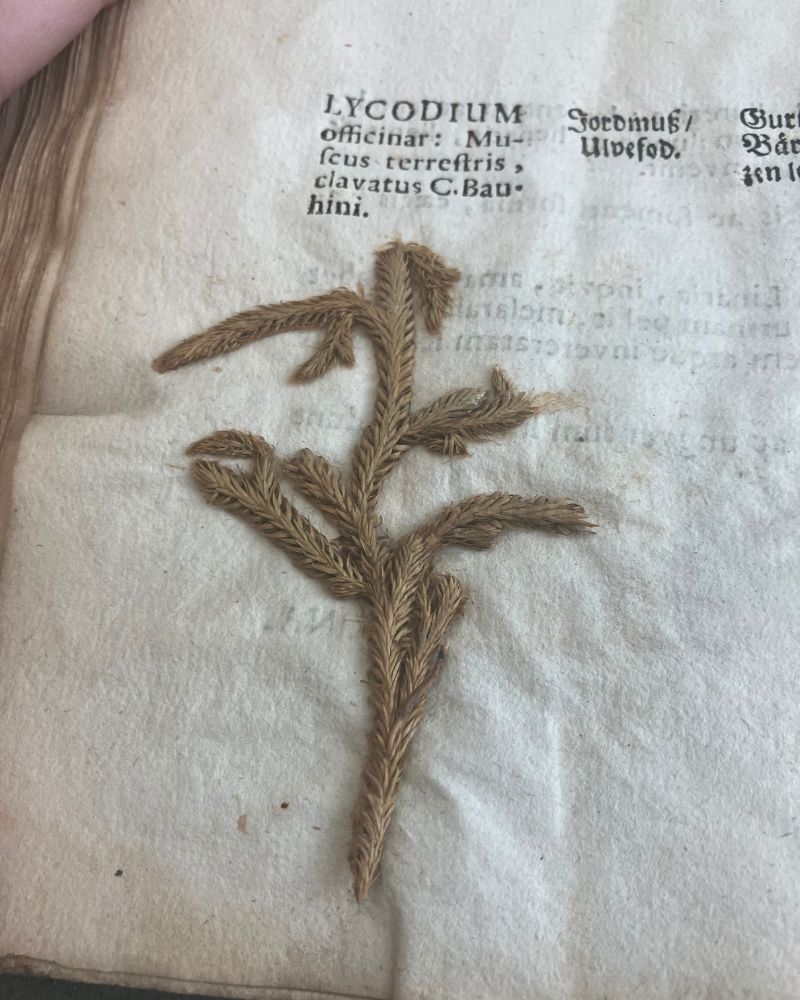

Herbarium pages make up the bulk of Specimen Botanicum. These consist of a specimen sheet on the left and informational text on the right facing page. The upper, outer, and gutter margins are consistent throughout the book: upper and gutter margins are 1”, and the outer margin is 2”. The lower margin is generally 3” on the recto pages, and in the introduction and epilogue sections before and after the specimen pages. However, on the verso pages with the specimens the lower margin is ill-defined. They may be understood as being standard 3” but invisible, or being half to seven-eighths of the page.

Page numbers appear at the top center of each page, surrounded by a symbol of flowers or possibly a sun. At the bottom of the recto pages there are additional alphanumeric classifications in the center, and the first three letters of the next specimen on the right.

The pages of specimen sheets have five columns as described in this table:

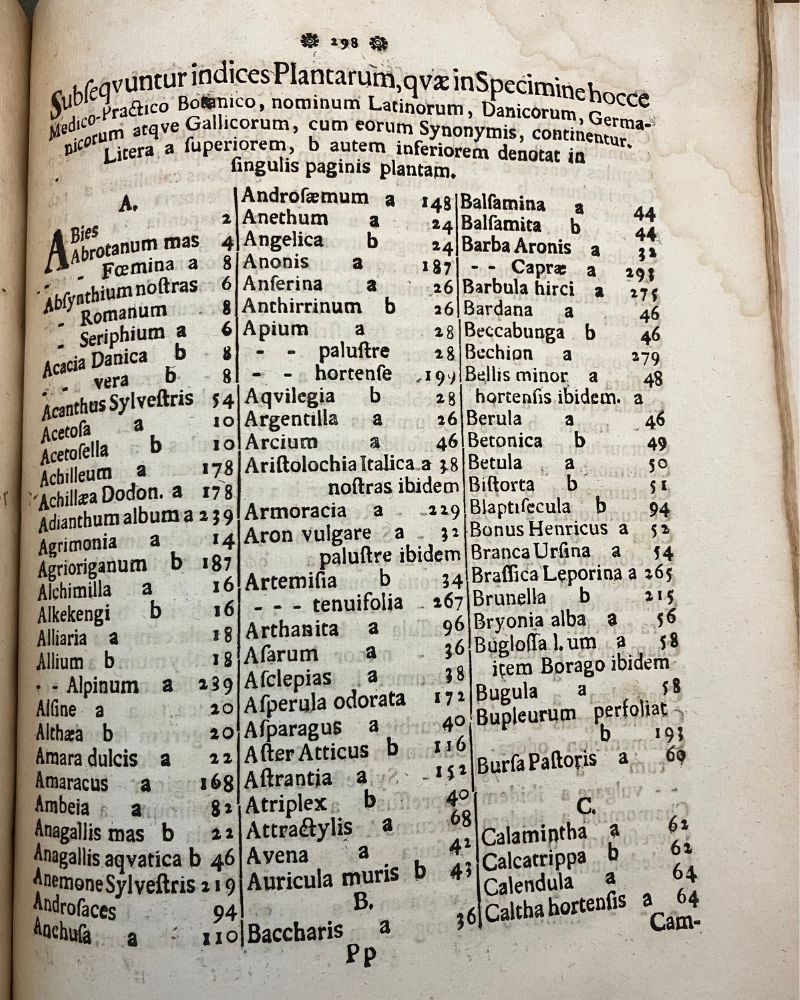

| Latine | Danice | Germanice | Gallice | Locus ac Tempus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of the plant in Latin | Name of the plant in Danish | Name of the plant in German | Name of the plant in French | Where and when the specimen was retrieved |

The layout of the printing must have required a good deal of pre-planning. The specimens are listed alphabetically but vary in size so each herbarium page may contain one or two records.

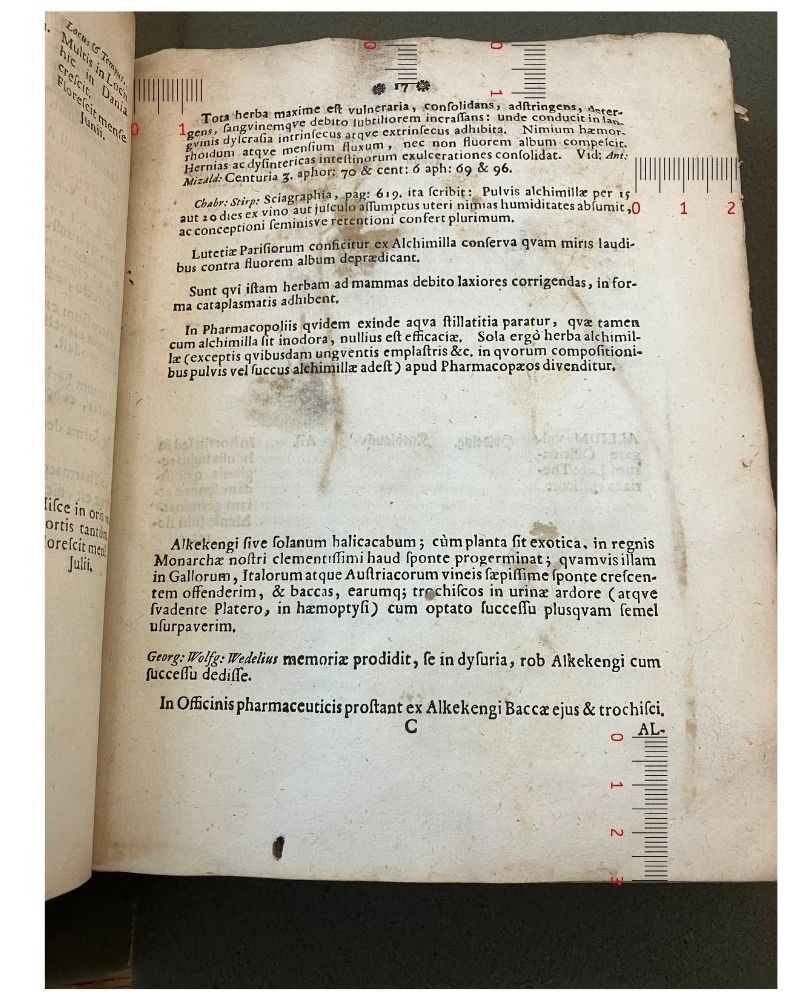

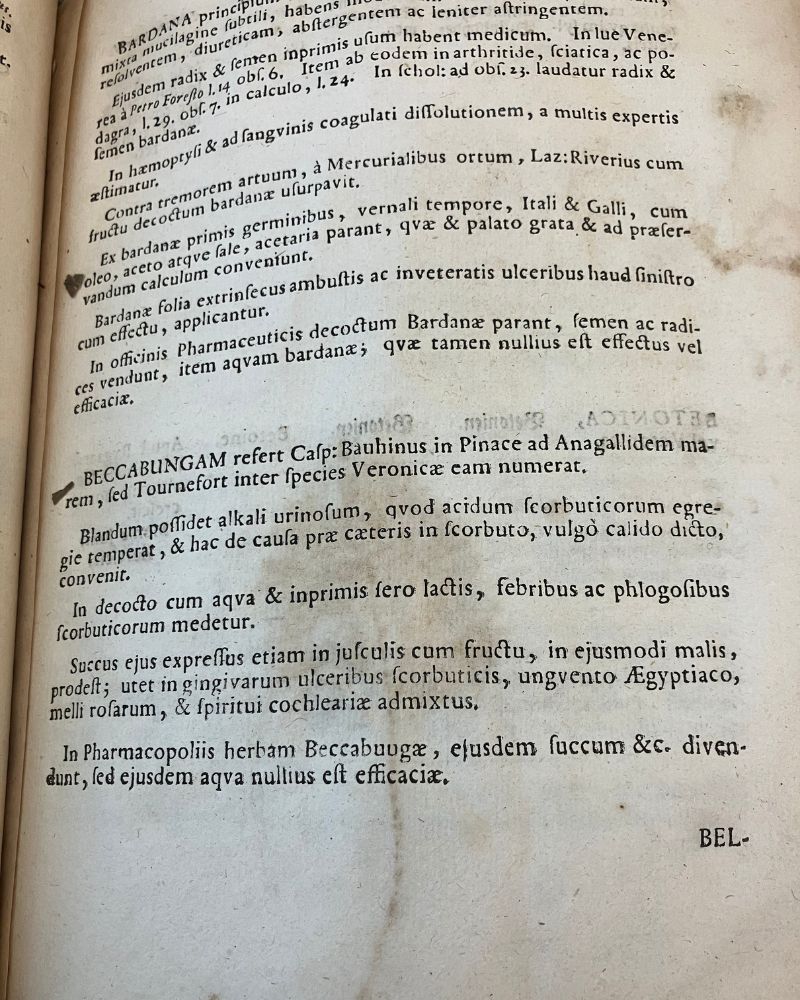

The text block on the informational pages is formatted in one column with justified paragraphs.

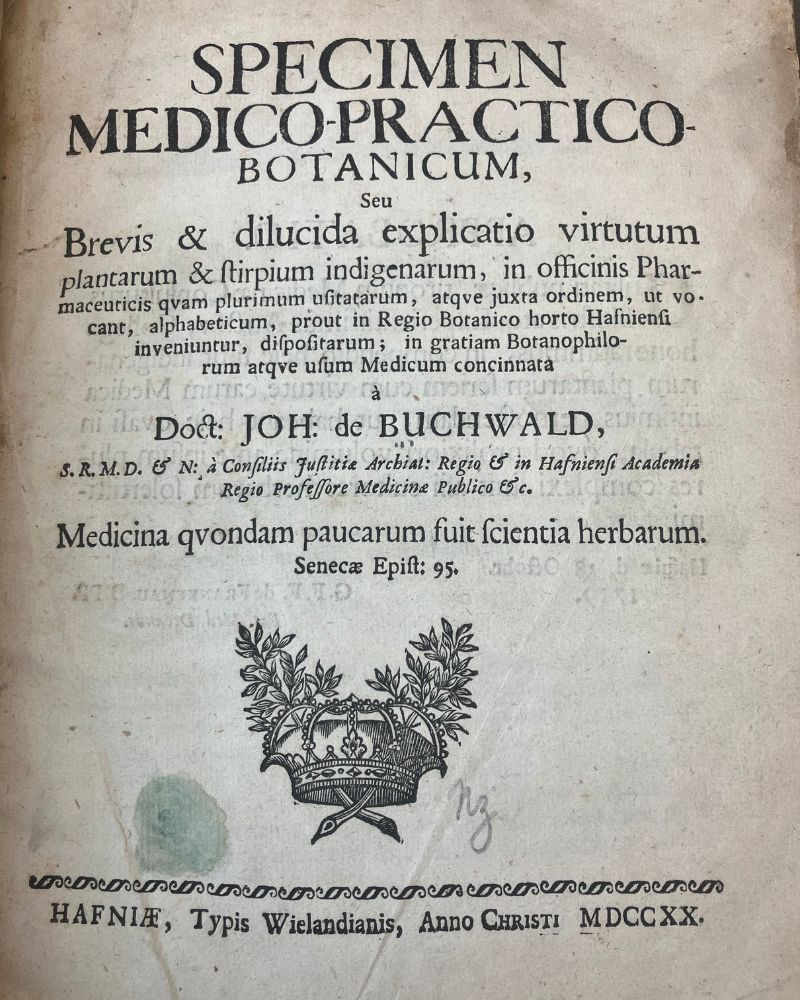

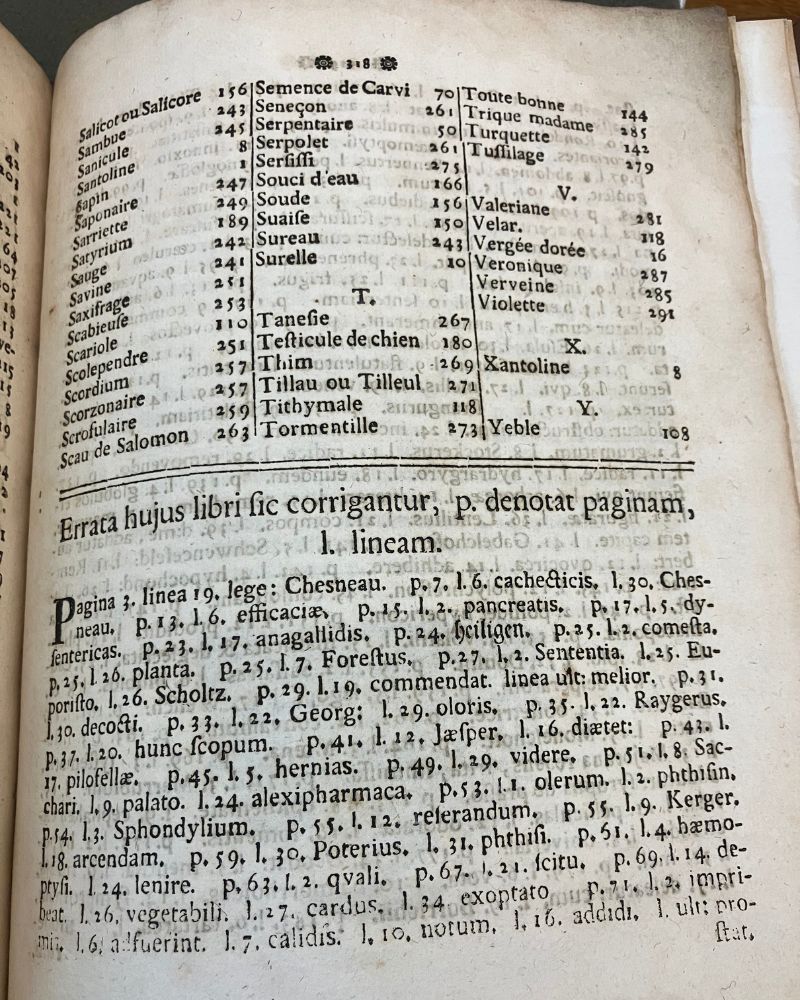

There is a title page and a prologue before the collection of specimens, and after them an epilogue followed by indexes in the four languages and finally a listing of errors and corrections by page and line. The title page is center justified. The indexes are introduced by a center aligned paragraph describing the contents. Then they are presented in three columns. The heading of the errata is also center aligned while the information is one column of justified text.

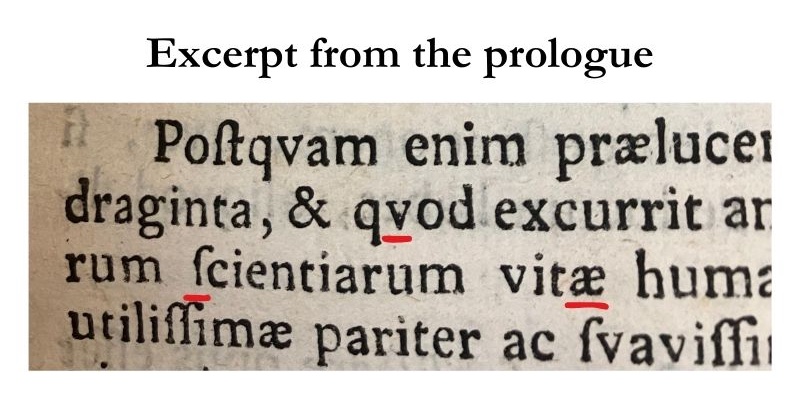

The prologue and epilogue are one column of justified text and begin with an illustrated five-line initial.

mise-en-texte

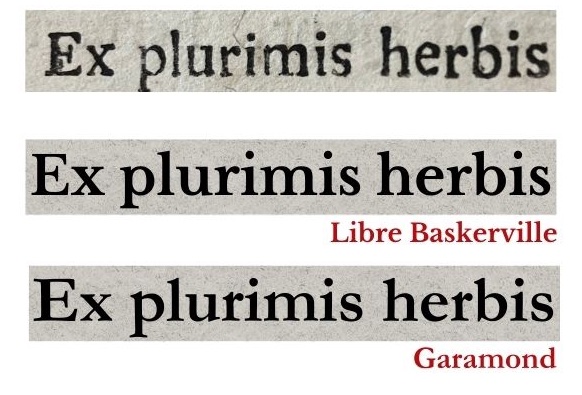

There are few different fonts used in the book. The main one looks similar to modern versions of Baskerville and Garamond (see comparison below). The introduction and epilogue appear to use that same font but utilize alternate letters and letter groupings, as well as the initial described above, to mimic earlier manuscripts. These flourishes do not appear in the informational pages.

The Latin, French, and time/place identification text on the specimen sheets are also in the same font (in the image below I used Garamond again). The Danish and German names, however, are presented in a more Gothic font (I used UnifrakturMaguntia below).

I find this interesting. Potentially it is meant to lend a kind of historic cachet to the record and the endeavor. Or possibly it is a nod to royal patronage: the author and the royal patron were Danish, and a year after publication the text was translated and reprinted in German. Maybe the choice is due to expediency or budget if those alphabets were more readily available in the older and bolder font. An example of the German version can be seen in Harvard’s collection and it does use the Gothic font throughout. Or it might be simply aesthetic.

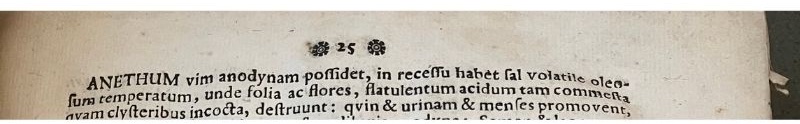

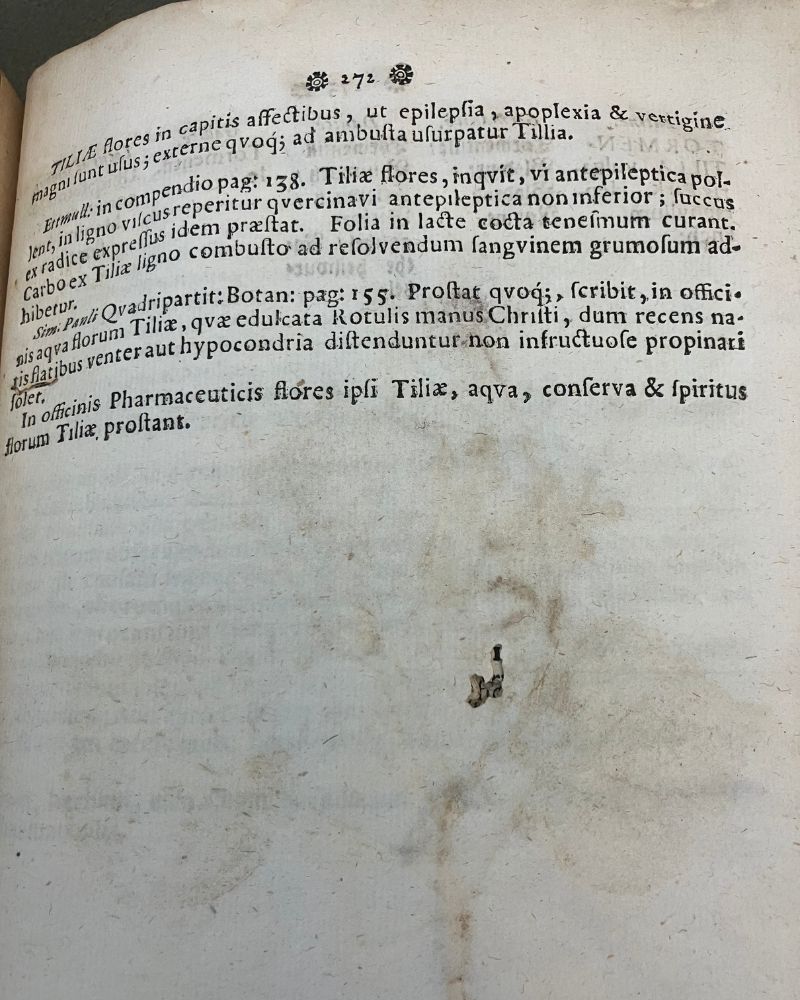

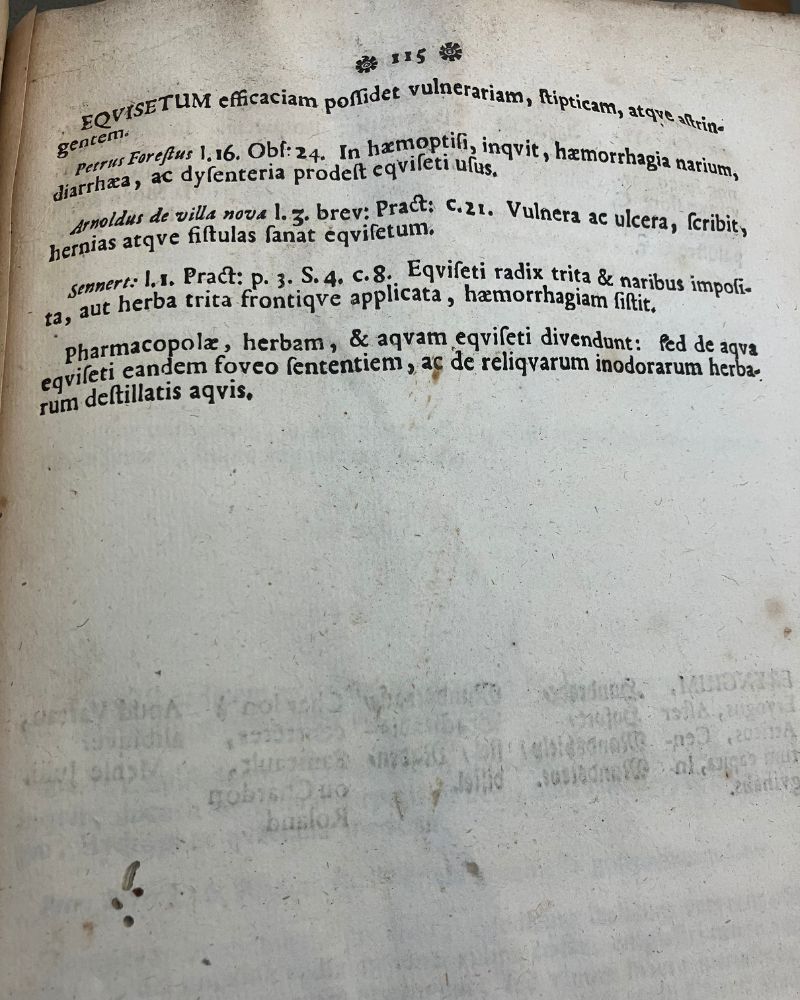

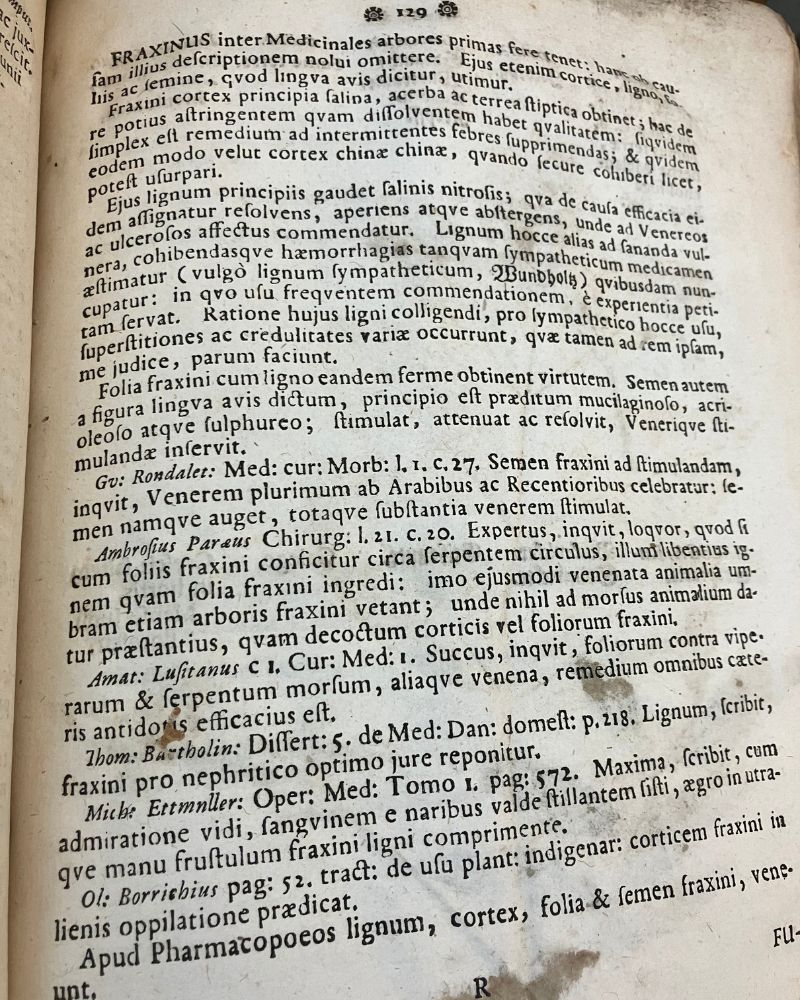

Each plant record begins with its name spelled out in all caps followed by the botanical and/or medicinal information. The number of paragraphs varies but they tend to be short and are all indented. Nearly all entries include abbreviations, reference and page numbers, and paragraphs that begin italicized. I cannot easily or reliably translate the records without additional context. But there is a resemblance to modern textbooks and/or informational pages in the presentation.

Here is an example of a brief entry. The text describes uses of the herb, in this case potentially related to equestrian activities. Note there is space between each paragraph.

Here is a much longer entry. The length is explained by the first sentence in the informational text: “Fraxinus inter Medicinales arbores primas fere tenet“ [Translation: “The ash tree holds almost the first place among the medicinal trees.”] This text includes alleged medicinal uses of the bark, leaves, fruit, and sap of Ash trees and histories of its use in China and by Arab people as well as Europe. There is no space between paragraphs on this page, and it looks crowded in comparison to the previous example.

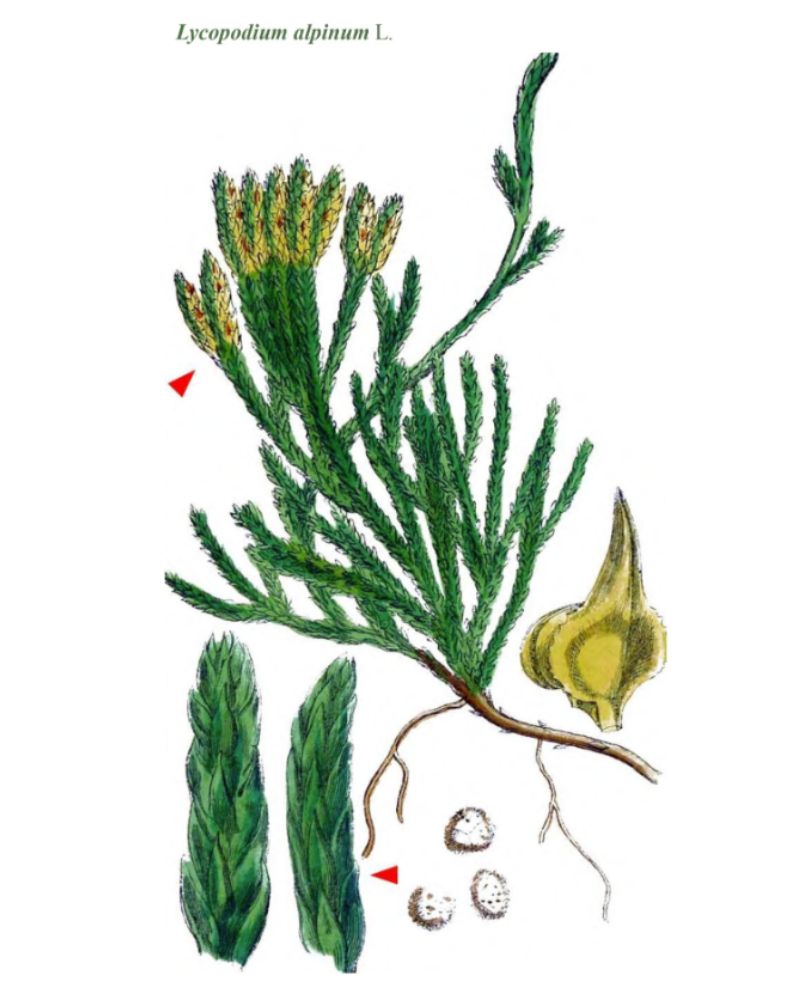

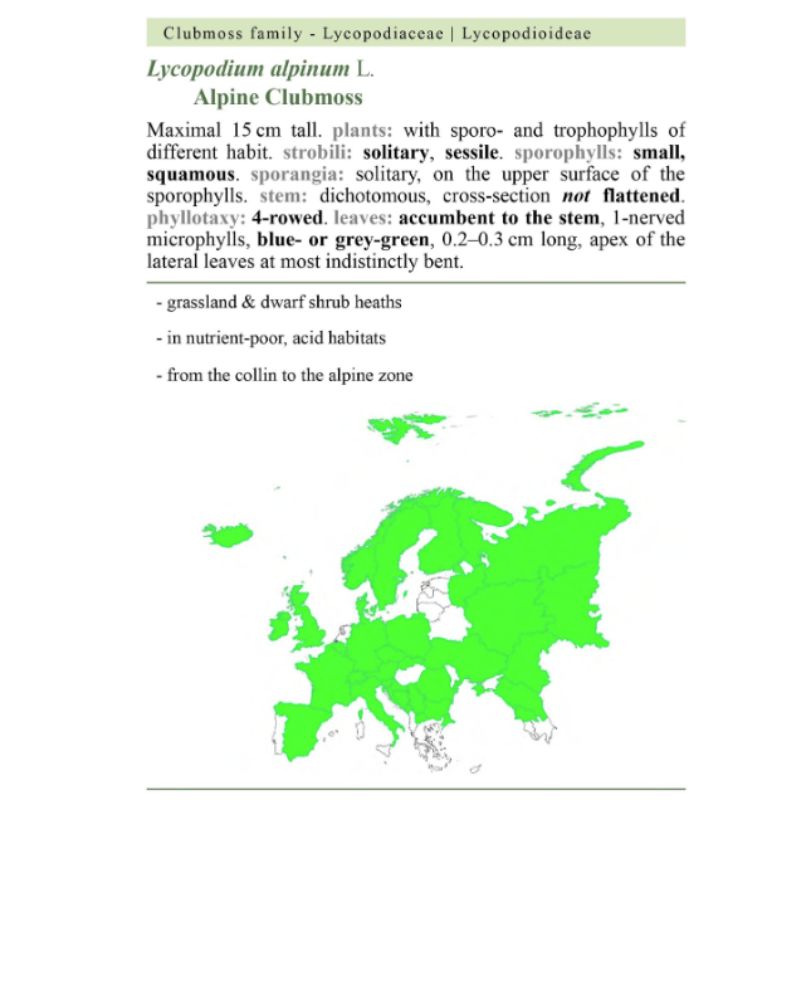

Finally, here are modern examples of similar books, Flora of Denmark (2019):

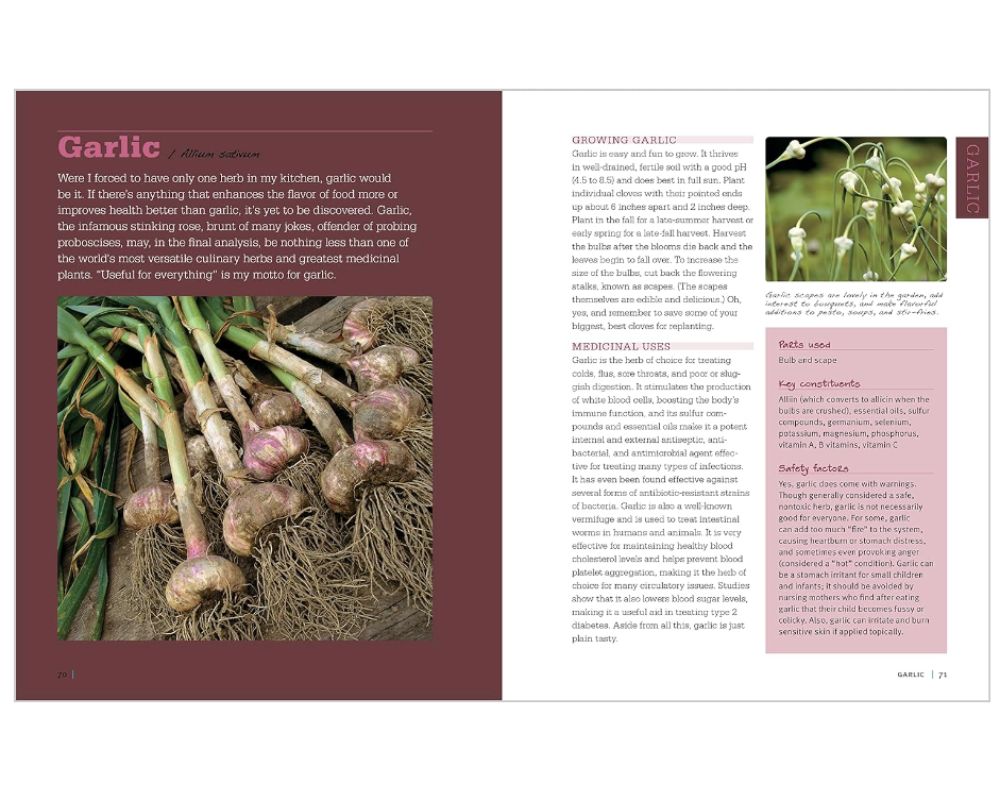

And Rosemary Gladstar’s Medicinal Herbs: A Beginner’s Guide: 33 Healing Herbs to Know, Grow, and Use (2012):

As you can see, the format of these two books references that of books like Specimen Botanicum despite the three hundred year gap between publishing, just as Specimen Botanicum references earlier texts with its choices in language, font, and paratexual elements.

Implicit

It is common sense that everyone who writes a little book, and makes it common through printing, seeks to gain the reader’s favor through a preface and to present the contents of the little book clearly to the eyes to avoid unhelpful judgements.

With this in mind, I also let this little prologue (preface) go out into the world after which I have spent over 44 years to see myself firmly in the nobility and never sufficiently praised for my herbal teachings. Although, regardless of all the effort I have put in, up to this hour I must also say: Quantum est quod ignoramus*!

*How much there is that we do not know.

Explicit

This [book] is based on many years of experience because I can best judge the effect of the plants by picking up each one and trying it on its own to get the truth from the well, so to speak. But if this has helped the common good in some way then I will be happy and thank God for it. If the imperfections here and there have their place in them (and where there is perfection in this imperfection) I will congratulate them and meanwhile along with the greatest men will gladly confess: non omnia poffumus omnes* and it will probably stay that way until the end.

*not all of us can do everything