This delightful and compact volume — 1928’s The House at Pooh Corner, written by British poet, playwright, and children’s book author Alan Alexander (A.A.) Milne — is very visual. That may sound patently silly, as most every book* is “visual,” comprising symbols and images that convey the book’s content and messages.

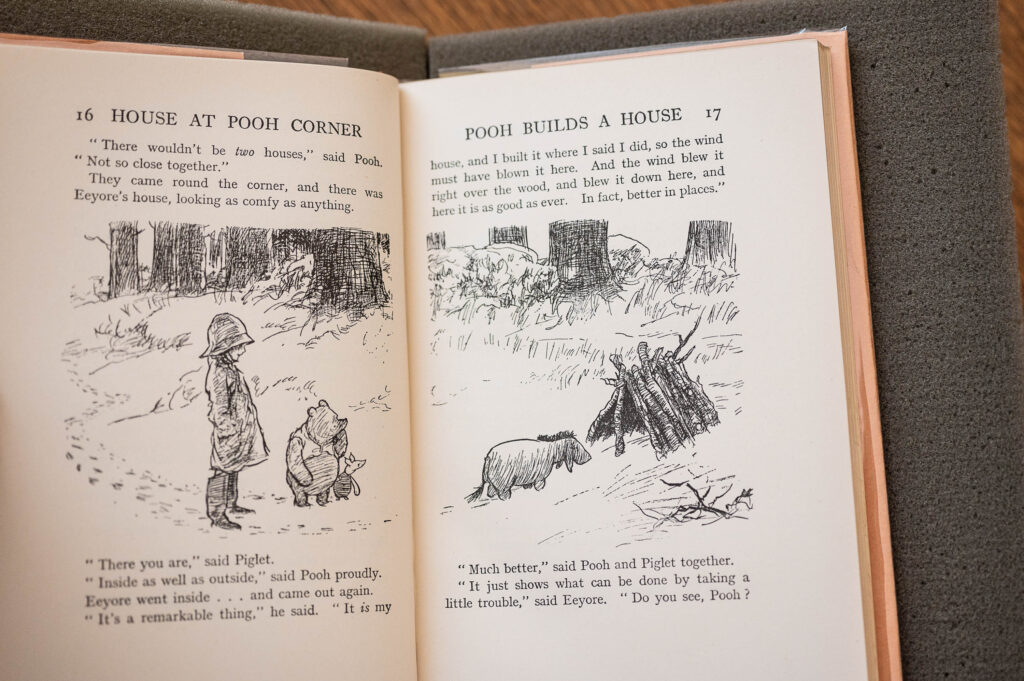

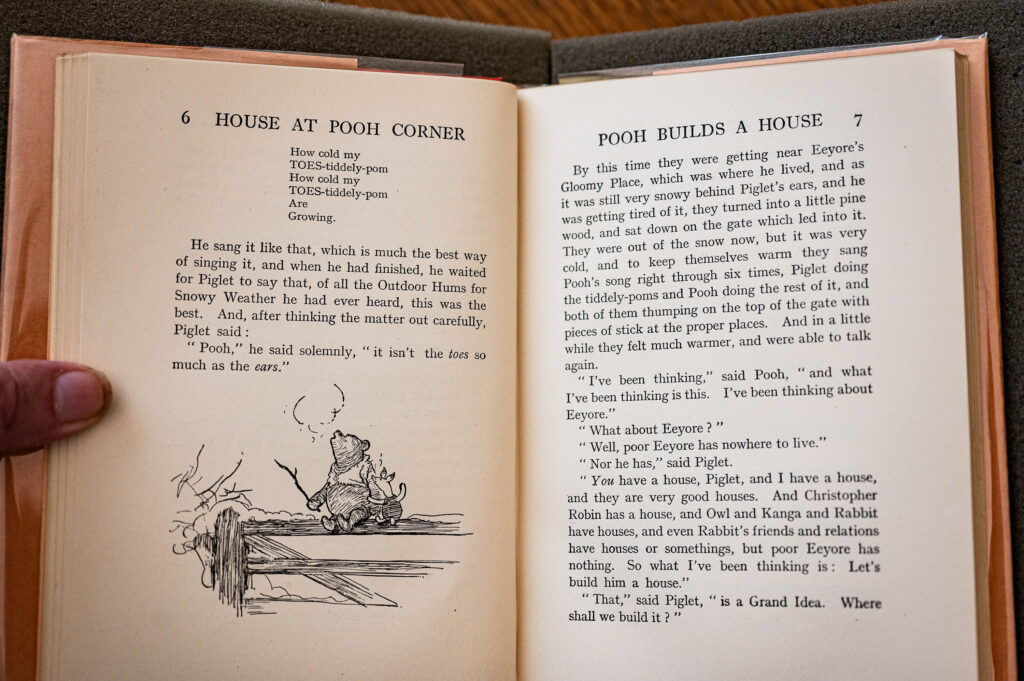

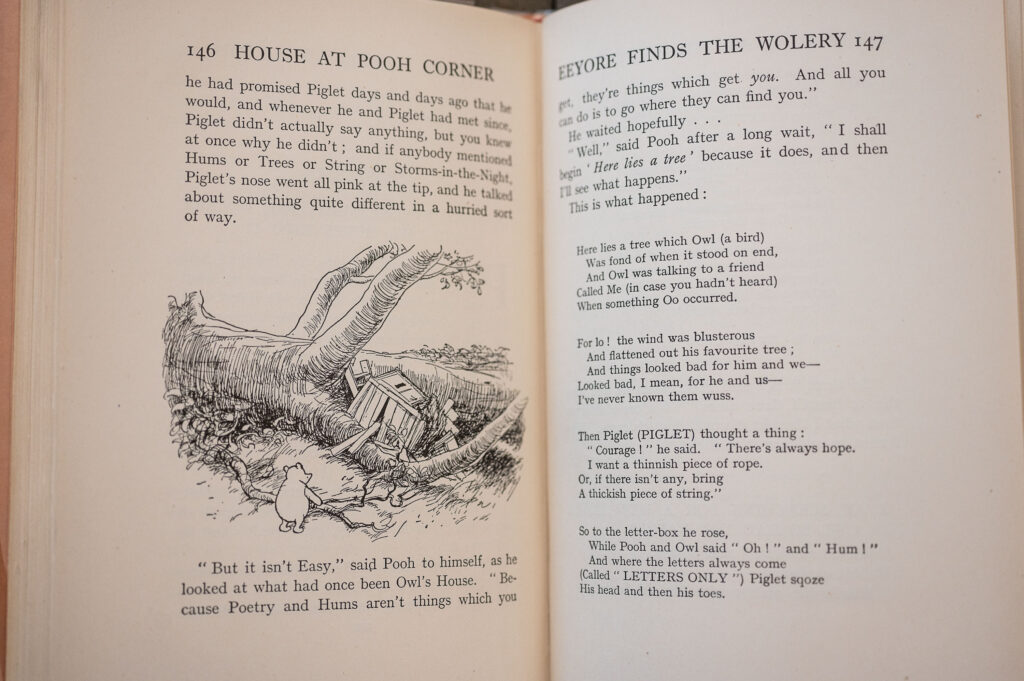

But The House at Pooh Corner is — as Winnie the Pooh himself might announce — “rather” (or very) visual, as it has been constructed with ample and skillful illustrations by Ernest H. Shepard. Shepard’s offerings are line drawings that amplify, supplement, or even stand in for the text, part of an elaborate and fruitful collaboration between author and illustrator.

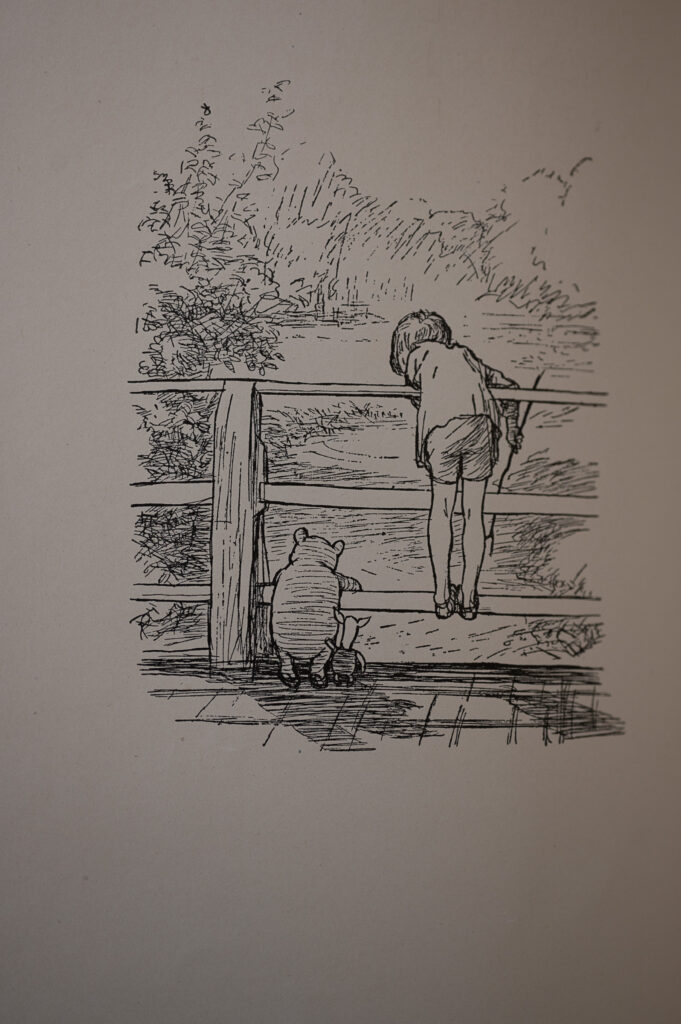

One such example of image-as-stand-in occurs on a left-facing page early in the book (an unpaginated verso in the position of “iv”), a feathery drawing of Christopher Robin, Winnie-the-Pooh, and Piglet straining out over the railing of a wooden bridge with their shadows represented by hashmarks on the planking, as the characters watch the river flow beneath them. The drawing is unbordered, meaning it flows organically from drawing to margin, without interruption.

There is no accompanying text on the page, but the message of friendship is as clear as it would be written in words, with Christopher Robin and Pooh leaning out over the river to improve their view, and with Piglet resting his left hand low on Pooh’s “shoulder.”

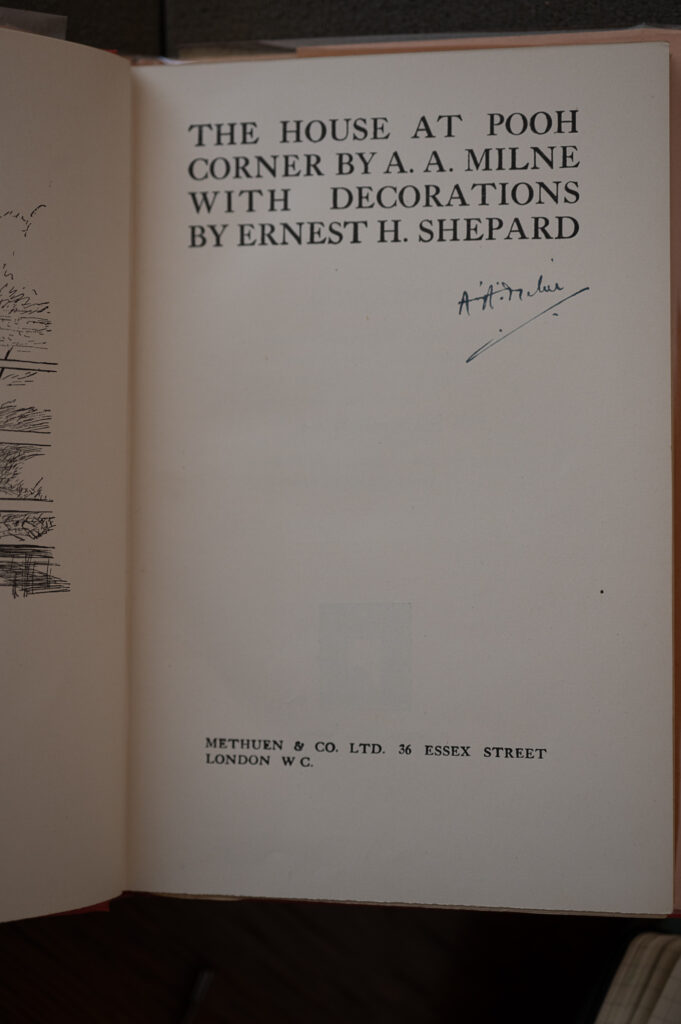

On the facing title page (recto) can be found the full title and enhancement:

“THE HOUSE AT POOH CORNER BY A. A. MILNE WITH DECORATIONS BY ERNEST H. SHEPARD,”

And just below that of this specimen is Milne’s scrawled signature, adding to the sentimental and retail value of the book.

At the bottom of the page is the identification of the publisher,

“METHUEN & CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET LONDON W.C.” and on the verso:

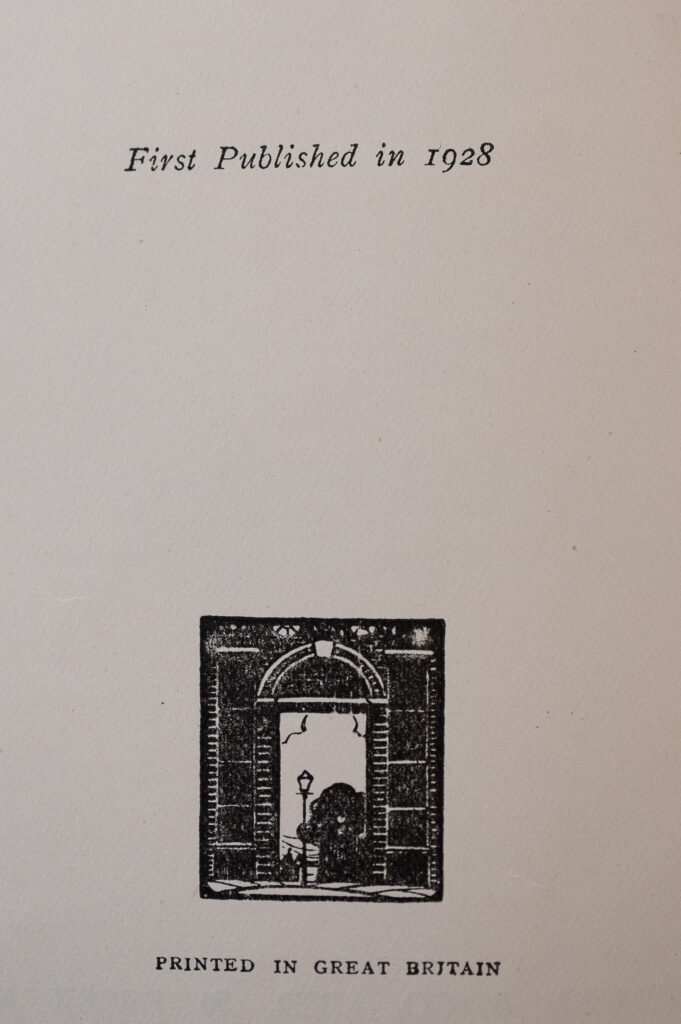

“First Published in 1928,” plus a Methuen colophon and ”PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN.” In my previous post, the printer is identified as Jarrold and Sons Ltd. of Norwich. Also in my first post, I offered something of an educated guess at the typeface used as the text, suggesting it might be the popular book typeface Baskerville, a serif font developed in the 1750s by John Baskerville and frequently used in 20th Century books.

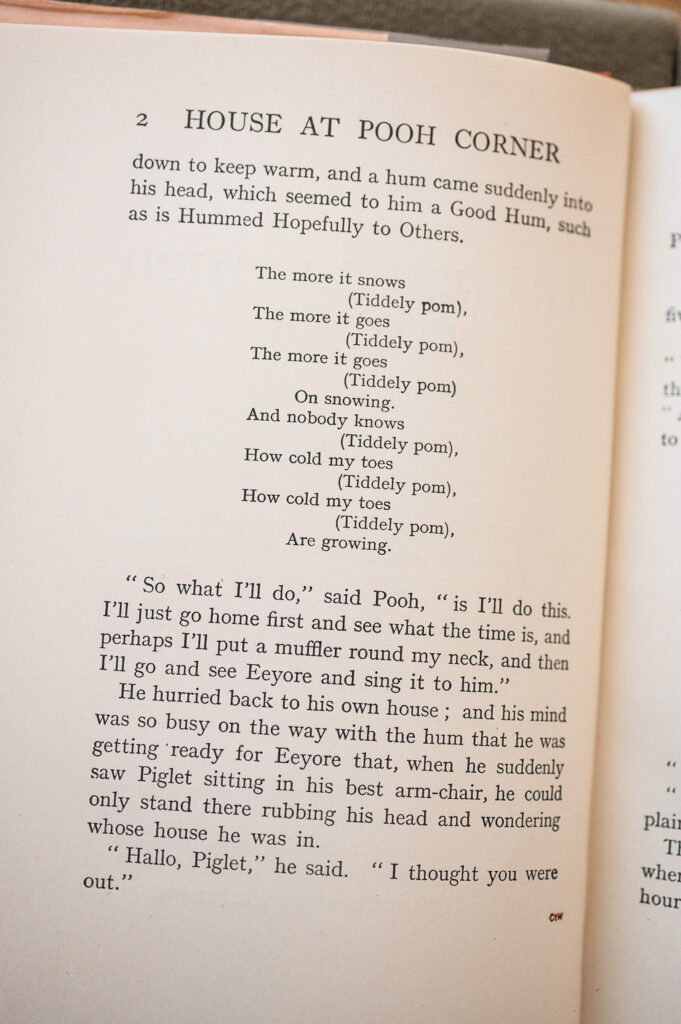

Earlier I called this book “compact.” In fact it measures about 18.5 cm tall, 12.8 cm wide, and just about 1.5 cm thick. The predominant design of the text blocks in this book displays a single column of text, or illustration, or a mix of the two. The text is justified, meaning that both edges of the text block are even, with letters proportionately spaced across the page — except when it presents songs or poems. With the justified text, the left and right margins are reliable: about 1.6 cm in the “gutters” (nearest the binding) and 2.6 cm on the “outside” edge. On full pages are 28 lines of 18.4 cm text, plus a “header” of a single line of text containing the Book’s title on the right side of verso pages, the Chapter title on the left side of Recto pages, and the page number on the “outside” corners of each. The first lines of each paragraph is indented about 0.4 cm. From the top of the page to the top of the header measures about 1.4 cm, and below the bottom line of text is a margin — bas de page — of just under 4 cm.

The ellipses in this book are, in my experience, unusual. Rather than treating each ellipsis as a word in its own right — three contiguous periods flanked by spaces — the periods themselves are spaced so that they run [period][space][period][space][period]

It is into this matrix of text and design that the illustrations are thoughtfully inserted, all as monochrome line drawings. Some of the illustrations use the entire width of the column, some are narrower than the full column but still break the flow as though they spanned the full column width, and seven —take up an entire page, offering no text whatsoever. The illustrations that are less wide than the entire column are positioned variously in the horizontal dimensions: centered, such as on Page 41, or positioned to the left (Page 42 an others) or to the right (Page 43 and others).

Also featured are columnar presentations of poetry and songs, such as one that occurs as a “Good Hum” — perhaps the best known “hum” of all of the Hundred Acre Woods — on Page 2 (verso):

The more it snows

(Tiddley pom),

The more it goes

(Tiddley pom),

The more it goes

(Tiddley pom),

On snowing.

And nobody knows

(Tiddley pom),

How cold my toes

(Tiddley pom),

How cold my toes

(Tiddley pom),

Are growing.

The book is often given over to Milne’s elaborate linguistic whimsy. Owl’s home tree is brought down by a gale and he searches for a replacement. When Owl announces his search is over, Pooh asks, “Have you found it, Owl?” Christopher Robin answers, peculiarly, “He’s found a name for it … so all he wants [lacks] is the house.” (155) Since Owl seems to suffer from a form of dyslexia, he soon presents a square board labeled: “THE WOLERY,” a misspelling of Owlry (purposeful on the part of Milne).

Around Page 163, it becomes clear that Christopher Robin’s advancing age will compel him to leave on a voyage, a coming of age, and that he will leave the Hundred-Acre Woods behind. Soon, everyone is writing songs to honor him; Eyeore’s is very popular, and I would transcribe it, but it takes up an entire page and so is a bit long for this post. The other characters have written songs, too, and they sign them. In a burst of innovation, Shepard has drawn the well-known characters along with each in-character signature: A scribbled “PooH”; “WOL” for Owl, with some hen scratch before it; “EOR” for Eeyore; “Rabbit” with a pretty flourish; “BLOT” (also pictured as a blot) for Tigger; and SMUDGE (likewise drawn and written) for Roo.

Shepard and Milne have likely cooperated on this passage, contributing recognizable values for the popular characters but also their own quirky signifiers in drawn text, rather than in standard typeset letters. Milne has always been known for his linguistic games.

~

Incipit:

ONE day when Pooh Bear had nothing else to do, he thought he would do something, so he went round to Piglet’s house to see what Piglet was doing. It was still snowing as hs stumped over the white forest track, and he expected to find Piglet warming his toes in front of his fire, but to his surprise he saw that the door was open, and the more he looked inside the more Piglet wasn’t there.”

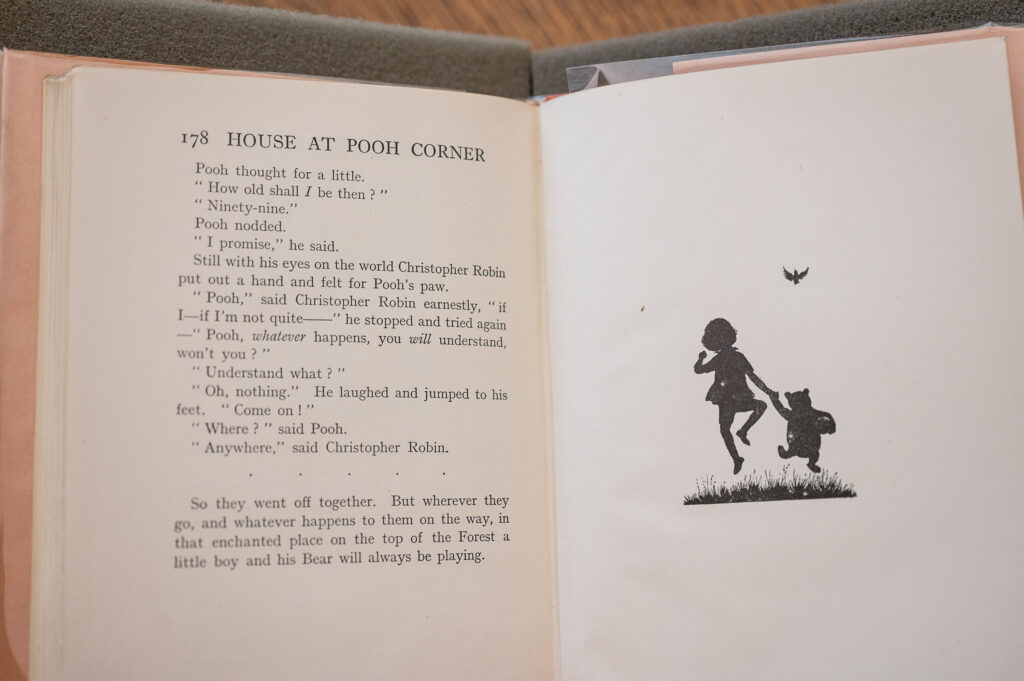

Excipit:

“So they went off together. But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.”

_____

* I say “most every book” in case there is a book I am unaware of that is somehow not visual, although at present I cannot imagine what that would be or even look like.