Pet Book Blog Post# 2

A Midsummer’s Night Dream by William Shakespeare with Illustrations by Arthur Rackham. London, Heinemann ; New York, Doubleday, Page & Co., 1908

A Midsummer’s Night Dream is a captivating comedy written by William Shakespeare in 1595/96. The play cleverly interweaves three separate plotlines surrounding the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. These include the whimsical adventures of four young Athenian lovers and a group of amateur actors, who are controlled and manipulated by the fairies who inhibit the enchanted forest in which most of the play is set. This 1908 edition features illustrations by Arthur Rackham whose enchanting visual interpretations beautifully capture the dreamy and magical character of Shakespeare’s text.

mise-en-page

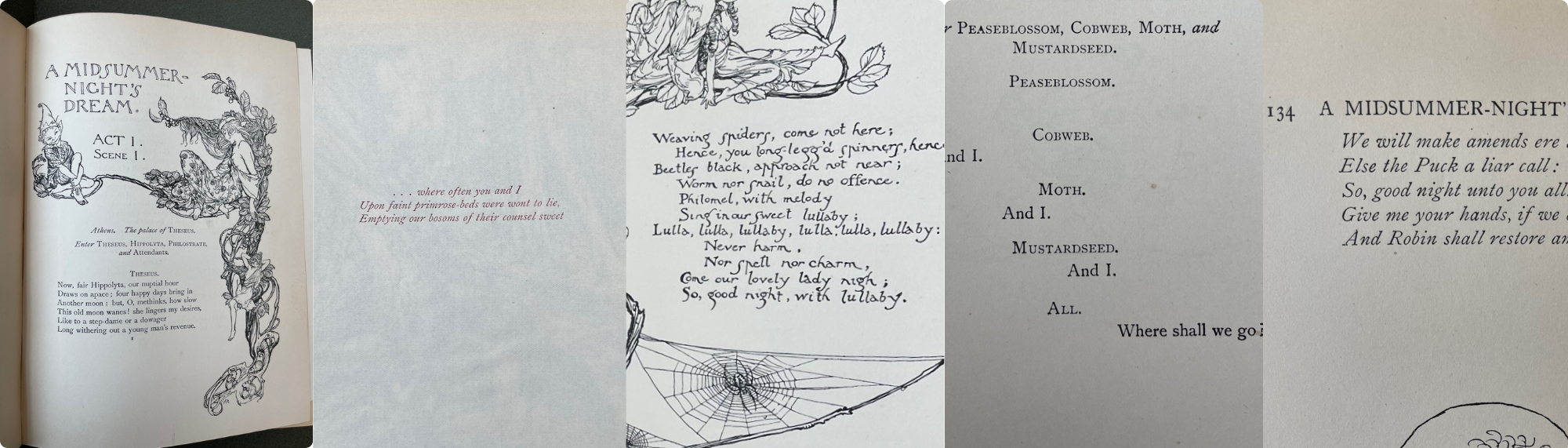

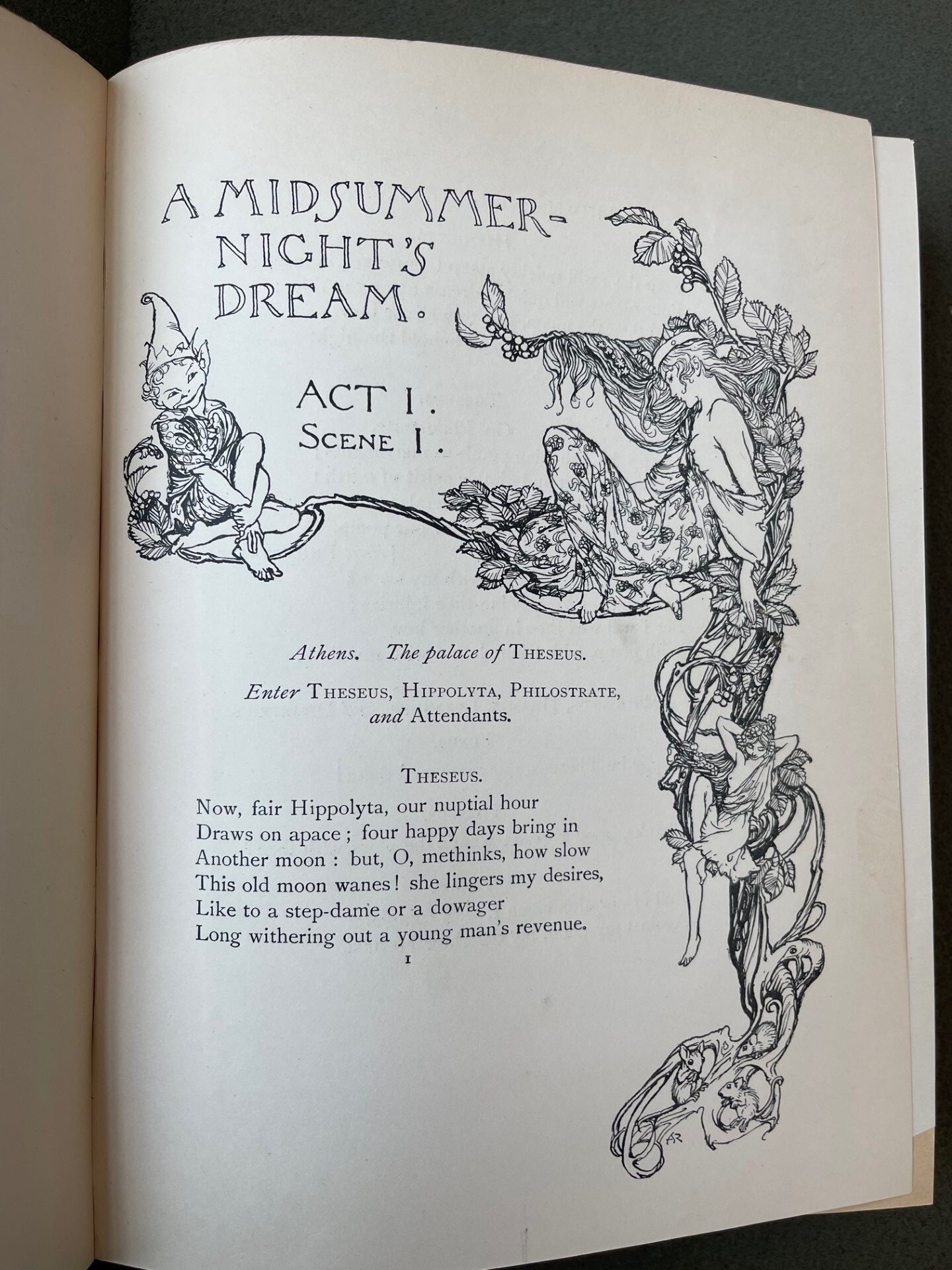

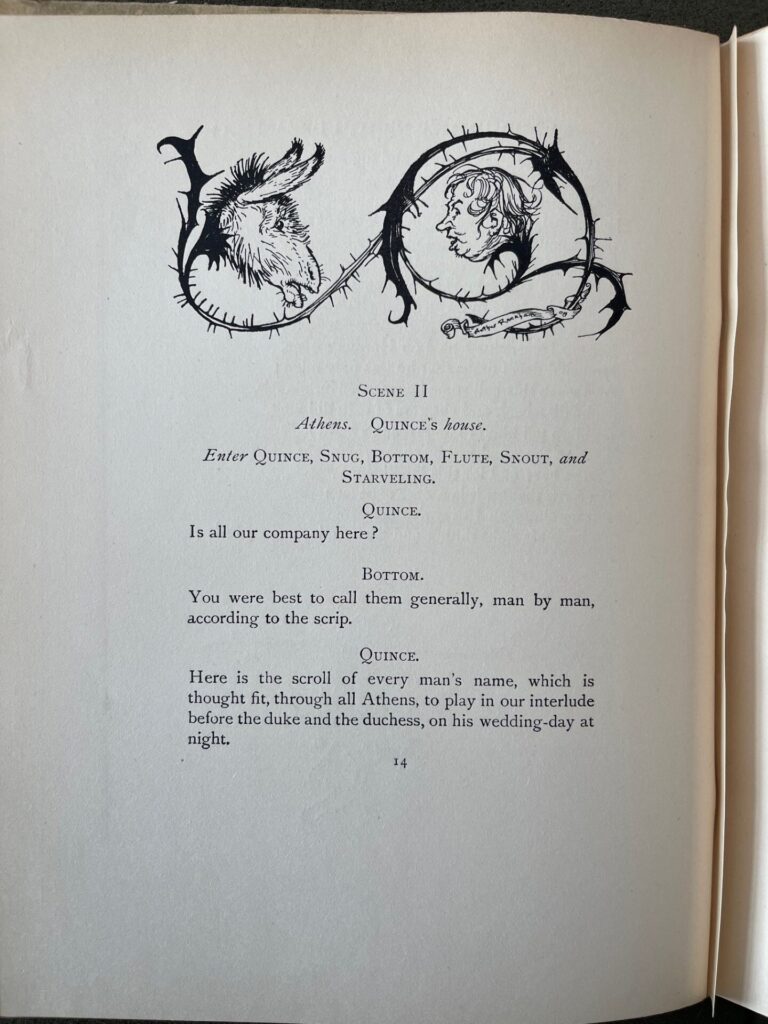

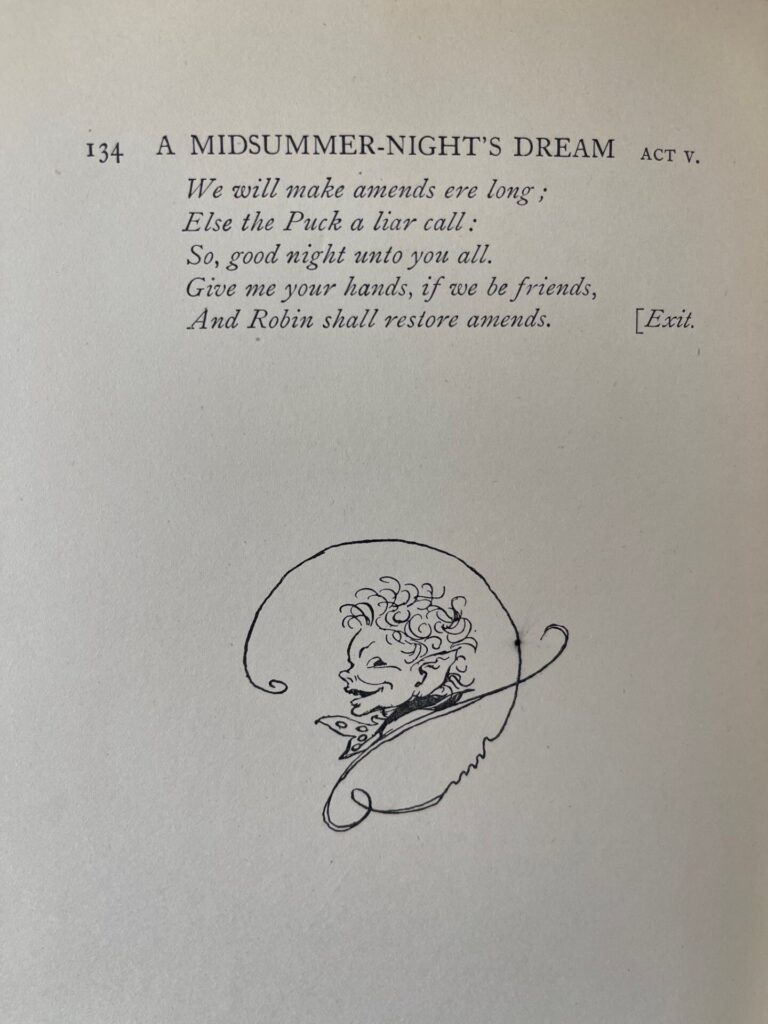

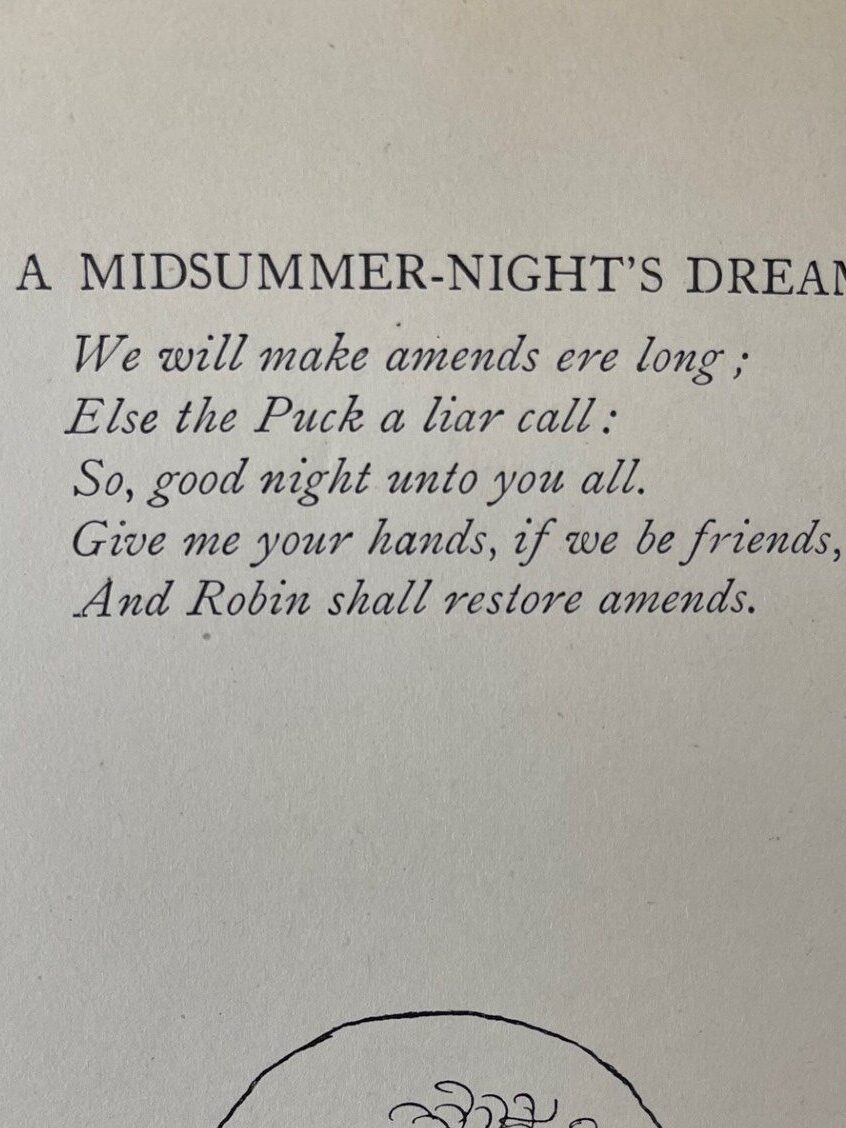

Like all of Shakespeare’s plays A Midsummer’s Night Dream follows a five-act structure, where each act is subdivided into scenes. Rackham masterfully applies his pen and ink illustrations to the smooth creamy colored woven paper to signify the start of each act. This is displayed below on the very first text page of the codex (see Act I, Scene I below), with an elaborate hand drawn title and image which wraps around the text and runs the full length of the page. In contrast, Rackham also inserts carefully placed miniature illustrations to effectively mark the start (see Scene II below) or end of a scene, as in the stylized portrait of the mischievous forest fairy Puck (see Pg 134, Act V below). This is significant choice by the publisher to use image not word as the final element of the entire codex.

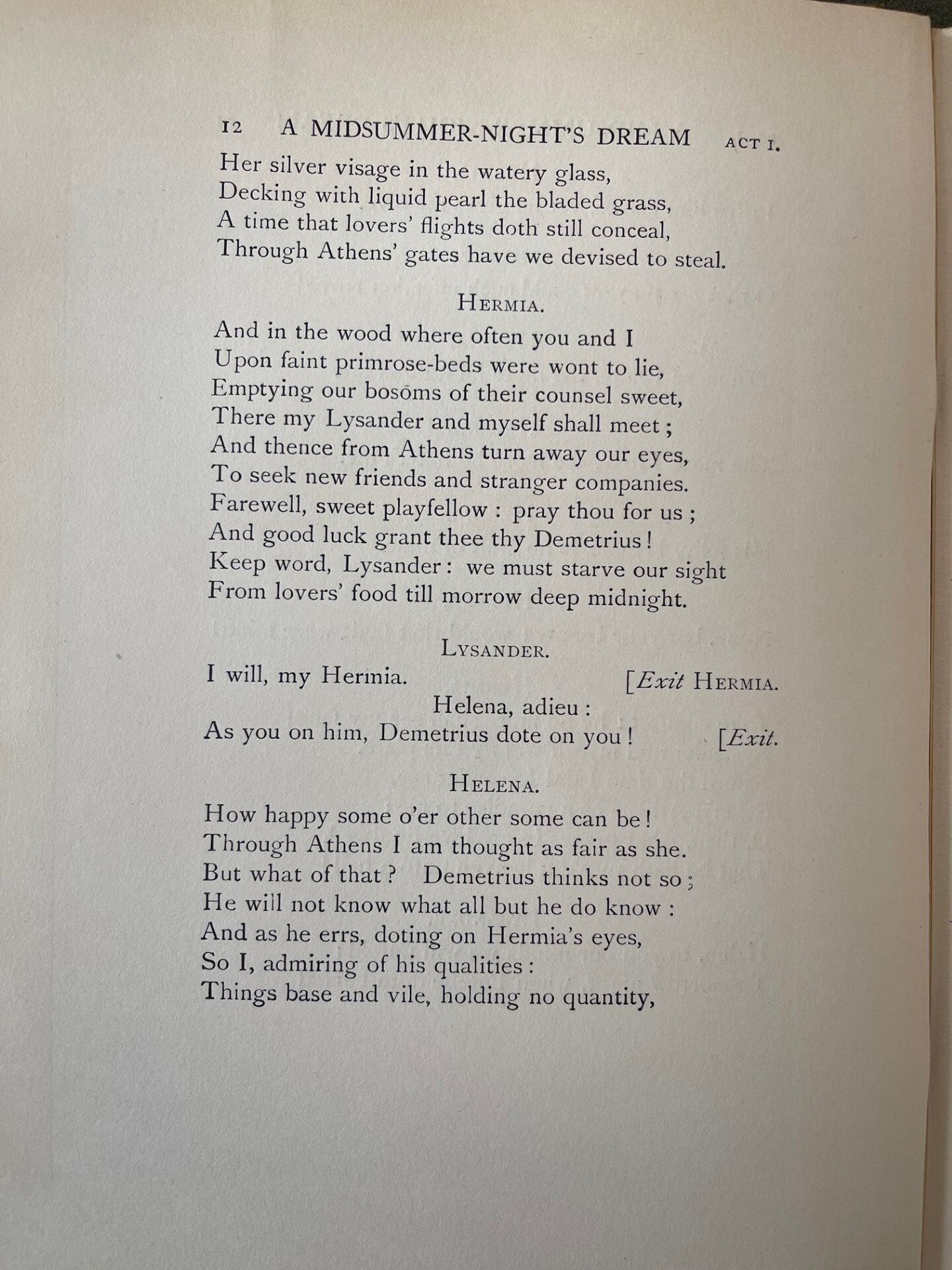

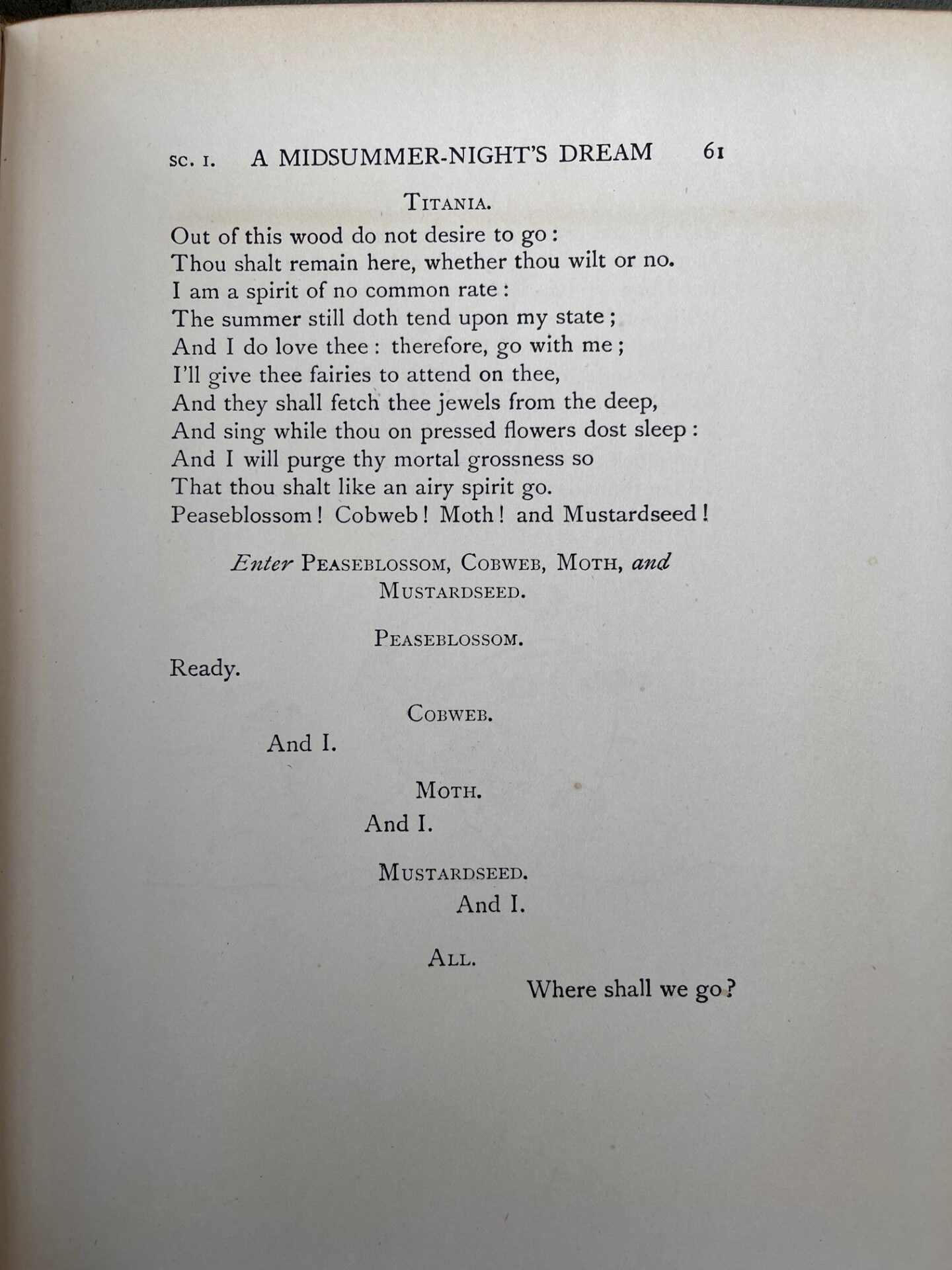

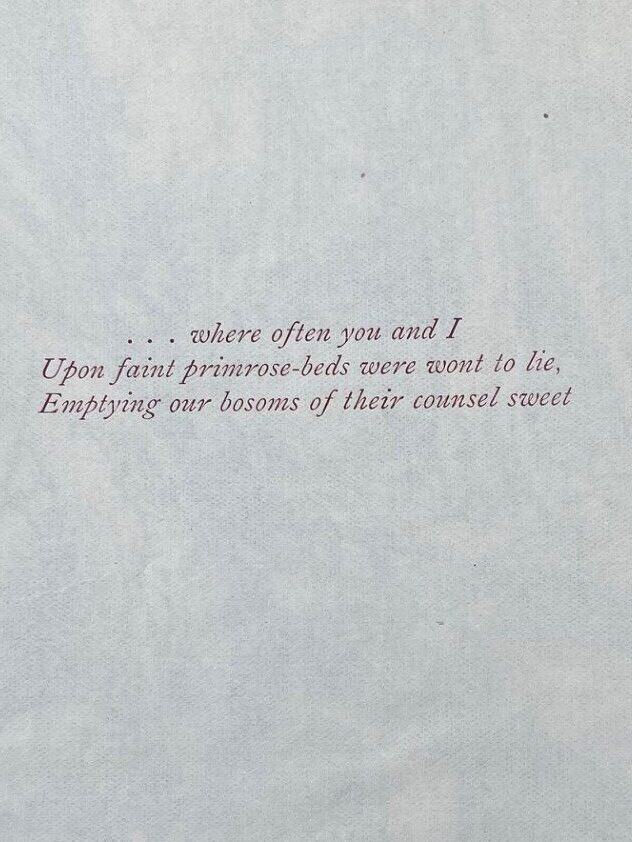

Generally, the text block is left aligned and set in one column within the upper section of the page which measures 9.5″ length by 7″ width. There is comfortable spacing surrounding the text block with 1” upper margin and approx 2” margins to the left and right. The lower margin however is noticeably wider and ranges from 2.75” to 7” on some pages. While the majority of the text block is left aligned there are sections of text which is center aligned and even an instance where the text literally dances across the play as the dialogue moves between our group of amateur actors, as seen on page 61. As one moves through the book you have the overwhelming feeling, that you the reader are also romping through a dreamlike realm like the characters of the story.

mise-en-texte

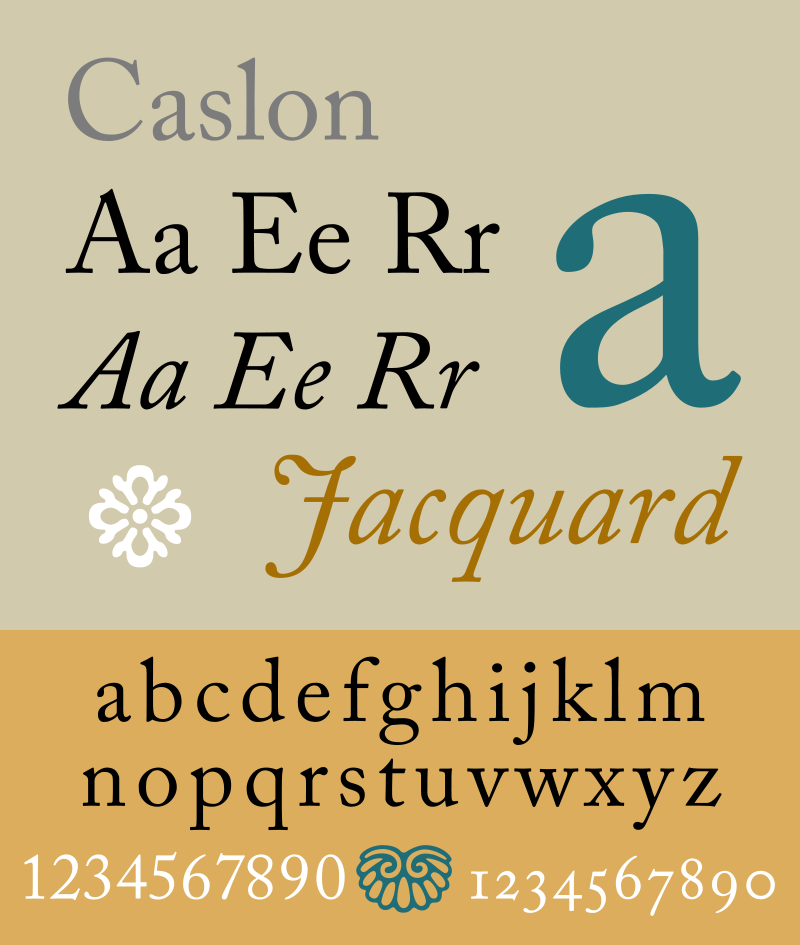

The text font is both elegant and easy to read. It has a timeless quality to it which both suits the written word of Shakespeare and compliments Rackhams drawings rather well. I suspect it is a version of Caslon which was commonplace during this period of commercial book making. One of the last pages informs us that this book was printed by Ballantyne & Co. Limited at the Ballantyne Press, Tavistock Street, London.

The running title is consistently positioned at the top of each page in the following format:

page number, the title of the play, Sc. # or Act # (rotating back & forth page to page).

I note that only the printed text pages are numbered, leaving one with the feeling that the pages of printed illustrations are precariously floating within the structure of the book.

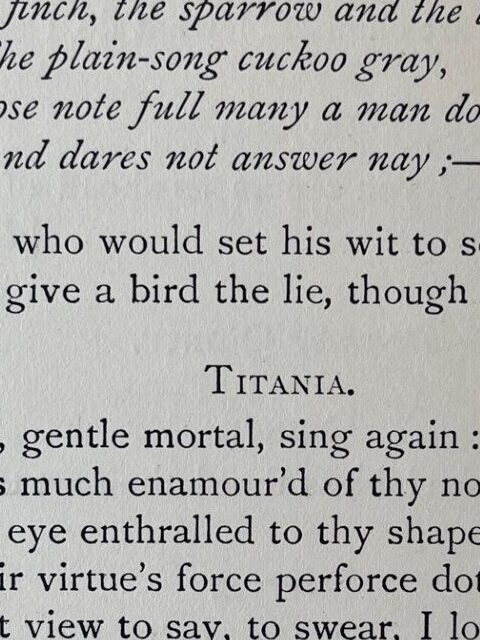

The main text is black ink color, whereas the italicized titles of the printed plates on the protective sheet leaf guards are in a reddish-brown color. Capitalization of the center aligned character names helps one follow the dialogue with ease. Stage actions, scene settings and sung sections of the play are italicized, assisting the reader to visualize the action of the story. As with all Shakespeare plays, the majority of the early modern english language is written in verse but for the more common characters such as the amateur actors, prose is used throughout.

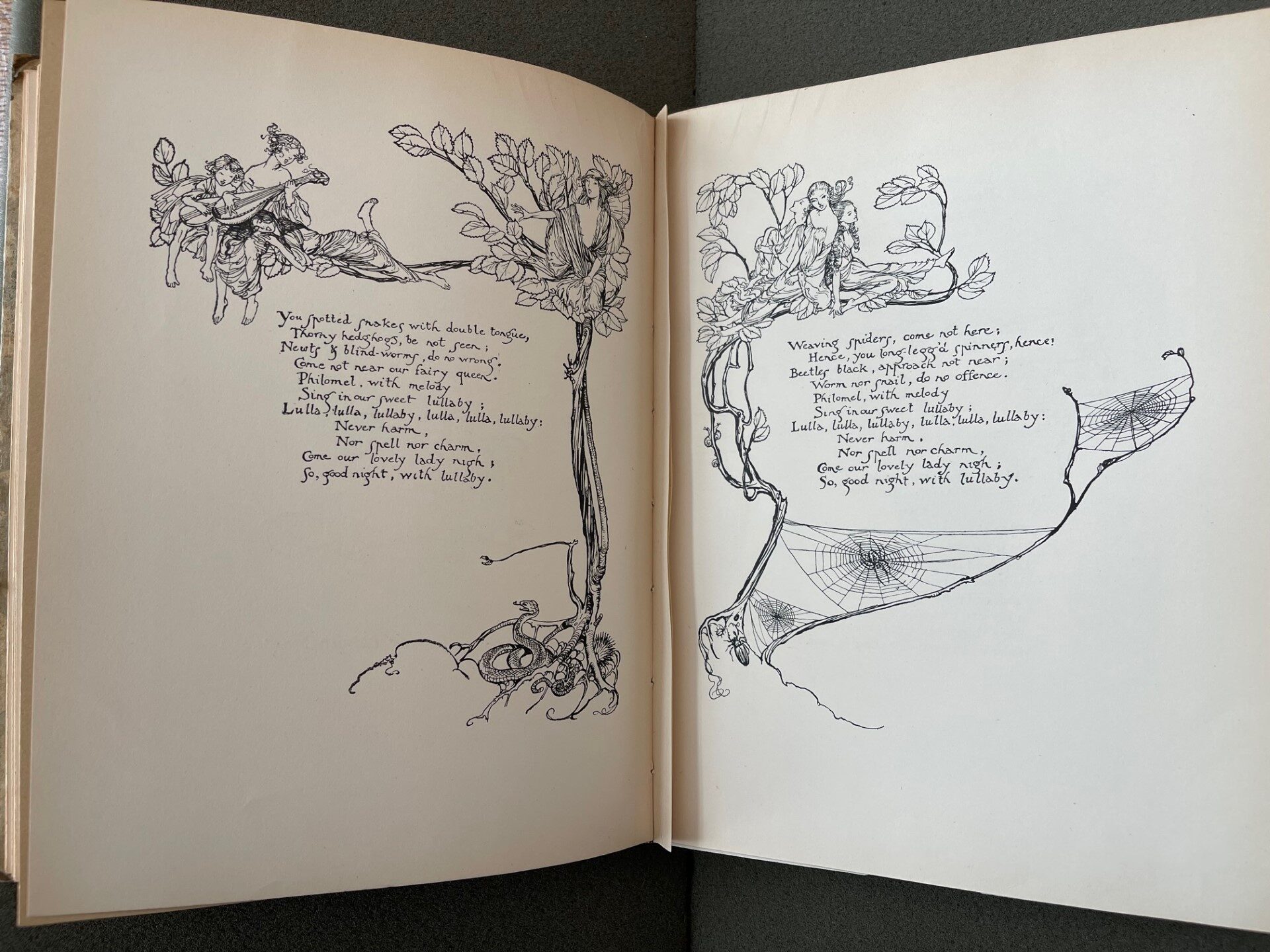

Rackham makes a significant choice to hand write ‘The Fairy Song’. His unique perspective on fairies and the alluring, whimsical world they inhibit is on full display here. Partnered with delicate pen and ink drawings, fairies are set in the branches of trees which stretch and sprawl out along the center and incase the stylized text. Word and picture become one image.

These are some of my favorite pages in the book and I suspect Rackham had a lot of fun designing this particular layout. As always his trees are a presence in themselves, beautiful and subtlety threatening.

As one looks through this book, you become aware that like the story there are multiple structures at play, one for the script and one for the illustrated drama as it unfolds. Like the subplots that are masterfully interwoven, the codex itself literally entwines the timeless writing of Shakespeare with the evocative illustrations of Rackham. As far as the readability of the book goes, at times it is not an easy and fluid act. I almost feel like these are two books disjointedly combined into one. I will explore this thought further with my next blog post when reviewing the illustrations.

In conclusion, while Arthurs Rackham’s illustrated treatment of A Midsummer’s Night Dream presents itself in traditional codex form, it does not always conform to traditional forms of textual organization which perhaps is a nod to the dreamy and whimsical nature of the play itself.

Incipit

Page 1, Act 1, Scene 1

THESEUS

Now, fair Hippolyta, our nuptial hour

Draws on apace ; four happy days bring in

Another moon : but, O, methinks, how slow

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires,

Like to a step-dame or a dowager

Long, withering out a young man’s revenue.

Explicit

Pg 134, Act V

PUCK

We will make amends ere long ;

Else the Puck a lair call :

So, good night unto you all.

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.